Small Man in a Book (22 page)

Read Small Man in a Book Online

Authors: Rob Brydon

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

On the town with Jacque and James.

We stayed together for two years and lived in a variety of flats and houses. When my time with Mrs Williams came to an end, I moved to an appalling

Young Ones

-style student house in Grangetown on a busy main road where heavily laden lorries and trucks charged past at all hours. We slept on a mattress on the floor while the architecture student in the room below worked to the sound of heavy-metal music turned up to eleven. I would wander downstairs bleary-eyed, knock on his door and ask him to turn it down, while he stood there looking as though playing music that loud at that time of night was the most reasonable thing anyone had ever done. The windows rattled through the night from the vibrations of the passing traffic, and I sellotaped cling film around their frames to keep out the cold. We’d stay up late and huddle under the duvet, listening in the darkness to Tom Waits and Crystal Gayle on the soundtrack album

One from the Heart

. The trucks rumbled by and the noise from the room below seeped up through the floorboards, but we were wrapped up and safe in our own little world. ‘It’s got to be love, I’ve never felt this way.’

11

Meanwhile, college life went on. With the exception of the more academic classes, like Theatre History, it was a doddle. Being able to make people laugh made everything that much easier, and already knowing what I wanted to do once I left college also helped. I knew that I wanted to be involved in comedy in one form or another, and I had a naively comforting belief that everything would be fine and that work would somehow come along for me. It’s virtually impossible, when studying acting as a student, to have any grasp of what life will be like in the outside world. There are always a few lucky ones who fall into work straight away, and some, luckier still, who find fame and fortune. But for the vast majority it is a dispiriting, endless slog of letters sent, CVs posted and auditions applied for – usually with very little coming back in the way of encouragement.

While in college, students are given the opportunity to play a wide range of parts. This is excellent experience, allowing them to stretch and test themselves, but it’s very unrepresentative of the real world. Having left the comfort of the college walls, actors are generally cast in accordance with how they look. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that they are cast in relation to how they are perceived. I wouldn’t learn this for some years yet, as my hoped-for career as an actor would have to wait while I took a few unexpected detours.

After our success on the

Level Three

radio show, I had become known to the Powers That Be (Powers That Were? Powers That Beed?

Powerful Bees?

) at BBC Radio Wales, and wasted no opportunity to make a nuisance of myself and remind them that I was eager and able when it came to radio. This persistence paid off one day when David Peet, the Director of General Programmes at the station, asked me to come in and audition for the role of holiday relief presenter on a twenty-minute mid-morning quiz show called

Bank Raid

. The programme involved a host talking to contestants on the phone and asking them questions about general knowledge. Successful answers helped the contestants progress towards the ‘vault’ where more successful answers would lead to an eventual winner, announced through the cunning deployment of a pre-recorded sound effect – in this case, the sound of coins showering down from a great height, signifying the sudden acquisition of not inconsiderable wealth. In reality the contestants won a book token.

The audition went well, and the job was mine. I replaced a staggeringly confident and capable young man named Mark Wordley, who flew abroad to his honeymoon. Were it not for this honeymoon, I might never have begun my career at BBC Wales where I stayed, on and off, for the next six or seven years.

Hosting

Bank Raid

was not a difficult job. The production team did all the hard work, finding the contestants, sourcing the questions and grouping them into categories. All I had to do was chat to the callers in a cheery manner, ask the right questions and play the correct effects cartridges. I managed this with ease and was eventually offered the job of hosting the show permanently. This would mean leaving college early, pretty much halfway through my three-year course, and without a qualification in the form of the diploma we were all studying for. I didn’t spend too long weighing up my options; it seemed clear to me that there was only one. It was a

job

, paid work, and in radio, which I had always loved. Surely it wouldn’t be difficult, once established as a broadcaster, to move across into the world of acting?

Hmm.

Readers familiar with the popular ITV game show

Family Fortunes

would do well at this moment to conjure up the distinctive sound of a wrong answer.

‘Rob says it would be easy to slide across into acting after being a radio presenter. Our survey says …’

I didn’t know it at the time, but it would prove very difficult indeed to make the leap. For now, it didn’t matter. I was working; I had money coming in, and life looked good. I had to tell the college that I was leaving and worried enormously that, when doing so, I would see a look in their eyes that told me they thought I was making the biggest mistake of my young life. I sat across a table from a couple of the senior staff members and told them my decision. In replying, one of them made the point that they were worried that I was drifting towards light entertainment.

Nonsense

, I thought to myself. Within two years I was bounding down a stairway in front of a studio audience, my hair bouffant, my jacket blouson, as I turned grinning to camera and welcomed viewers at home to a Saturday teatime quiz show called

Invasion

. Touché.

I don’t know if the cautionary words of my tutors were a real concern to me; I was too excited by the prospect of work, by the idea of getting out there into the real world and paying my way. I rented a large ground-floor flat on Cathedral Road. I’d coveted these huge, bay-windowed, high-ceilinged abodes for some time and moved in as soon as I could. It was only once tied into a contract that I realized that I would be sharing the place with a large family of confident, outgoing slugs. The road runs parallel with the River Taff and, I was told later, this was the reason so many slugs wanted to make friends with me. You wouldn’t see them during the day – they were busy, I suppose, or sleeping off the excess of the previous night – but come the evening they treated the place as their own. They would climb the walls of the bathroom and creep slowly across the bedroom floor under cover of darkness, only to be discovered when my bare foot came down unknowingly on their soft jelly-like form and ended their short life.

Aside from the slugs it was a good place to live, midway between the city centre and the BBC – where I found it possible to spend a large amount of my time, quite disproportionate to the length of the show I was hosting.

Bank Raid

was a small portion of a longer, mid-morning magazine programme called

Street Life

, hosted on alternating days by folk musician and broadcaster Frank Hennessy and rugby legend and broadcaster Ray Gravell. The brilliant Ray had played for Wales and the British Lions, as well as being part of the Llanelli team that had famously beaten the All Blacks of New Zealand by 9–3, back in 1972. (The town’s Wikipedia entry proudly notes that the score would have been 10–3 in today’s scoring system.) Ray was one of the loveliest people you could ever hope to meet, a huge gentle bear of a man who made everyone he spoke to feel that they were the most important person in the world. He was a very honest man and enjoyed our handovers, when we would switch from his show to my little section.

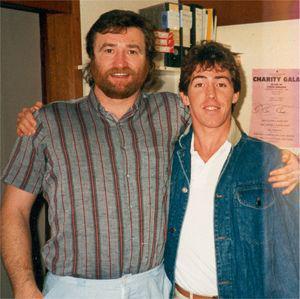

With the mighty Ray Gravel – ‘Tell me to fuck off ! Tell me to fuck off !’

I once asked him, on air, ‘How’s it hanging?’ I honestly had no idea what the phrase meant; I thought it was a figure of speech.

There was an awkward pause, a moment’s dead air, before Ray responded with admirable frankness, ‘Well, since you ask, to the left.’

I stayed in touch with Ray right up until the end of his too-short life. Years later, when I had achieved some success and had begun to make a name for myself, he would phone me out of the blue, for no other reason than to tell me he was proud of me and to congratulate me on how things were going. People often call out of the blue once you’ve found success, to wish you well. While I don’t doubt their sincerity, the conversation often ends with something along the lines of, ‘Oh yes, I know what I meant to ask you; we wanted to go and see Peter Kay, but it’s sold out. You couldn’t get hold of any tickets, could you?’ It’s fine – I do it myself – but Ray never once had any such epilogue to his calls. He really was just calling to say well done.

Ray particularly liked it when I insulted him. While we worked together at Radio Wales, I would make him laugh with my impressions of Al Pacino. These, in essence, amounted to no more than me pulling a vaguely Pacino-esque face and shouting, ‘Oh, Ray! You piece of shit! Fuck you!’

He loved it. ‘Aw … crikey! Tell me to fuck off! Tell me to fuck off!’

In 2000, at the age of forty-nine, Ray was diagnosed with diabetes, which eventually resulted in him losing his toe. This was followed by the loss of his foot. I saw him a little while after the amputation, when we both appeared on a television show hosted by our friend Max Boyce. Ray now had a prosthetic lower leg, on which was emblazoned the crest of his beloved Llanelli Rugby Club. He had lost weight, but was full of beans; he moved quickly on his new foot and, as usual, was only concerned with how I was doing, how I was feeling.

Two weeks later, he died after suffering a heart attack while on holiday in Spain. He was a truly great man, and the world was a better place with him in it.

I hadn’t been at Radio Wales for long when I was offered the opportunity to take over the early-morning slot: six thirty to seven thirty. To start with, as had been the case with

Bank Raid

, I sat in for a week while the regular host, Roy Noble, took a break.

This would have been 1985 or 1986; compact discs were beginning to emerge but, like many radio stations, BBC Wales was still using mostly vinyl records. Each day I would pick up the programme box. This was a sturdy black case, big enough to hold about twenty or thirty long-playing records, with a large and – to me, at least – strangely intimidating BBC logo stamped on the front. It contained the records and the running order for the next morning’s show. The running order was a script of sorts, which listed the sequence of the records along with any other features within the programme, such as news, sport and weather. Next to the title of the record was printed its duration and the length of the introduction, also whether the record ‘ended’ or faded – essential information for any disc jockey serious about his craft.

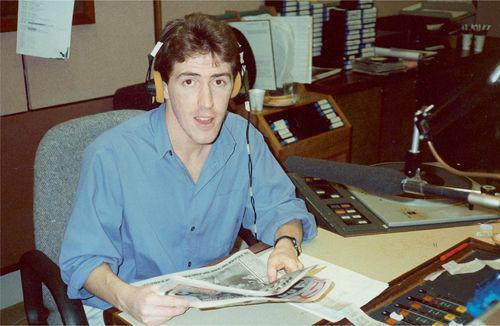

At Radio Wales. Poptastic.

Once back at Slug Towers, I would sit at my record player and practise my links, i.e. what I planned to say in between the records. In the very early days I even used to script these seemingly off-the-cuff and certainly inconsequential bits of chat. Frankly, it terrified me. Most people getting to host a national radio show would have risen up the ranks of hospital or perhaps local radio. Their on-air personality would have formed gradually, at its own pace, away from the pressures of such a relatively large audience. Here I was, thrown in at the deep end.

On my very first morning, as I approached the Greenwich Mean Time pips at seven o’clock, I trotted out my pre-written line.

‘You’re listening to BBC Radio Wales, I’m Rob Jones, it’s seven o’clock …’

Nothing.

Silence.

I’d peaked too soon.

I started again. ‘I’m Rob Jones and you’re lis–’

BEEP, BEEP, BEEP, BEEEEEEEEEP

.

Oh God.

Those early shows were a very bumpy ride; I would get quite worked up and panicked at the prospect of making a link run to a specific time. For a long while, as ridiculous as it sounds, the sight of a needle three-quarters of the way across a forty-five rpm single would bring on a mild but effective bout of anxiety.