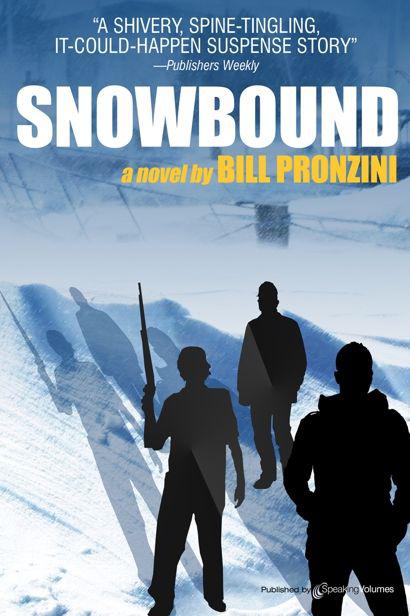

Snowbound

Authors: Bill Pronzini

Other Books by Bill Pronzini

The Hangings

Firewind

With an Extreme Burning

Snowbound

The Stalker

Lighthouse (with Marcia Muller)

Games

“Nameless Detective” Novels by Bill Pronzini

The Snatch

The Vanished

Undercurrent

Blowback

Twospot (with Collin Wilcox)

Labyrinth

Hoodwink

SPEAKING VOLUMES, LLC

NAPLES, FLORIDA

2011

SNOWBOUND

Copyright © 1974 by Bill Pronzini

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission of the author.

9781612321028

For Bruni, Who Suffered Too

and

For Clyde Taylor, Who HAD Faith and Several Good Ideas

and

For Henry Morrison, Agent 001

Monday, December 17,

Through Saturday, December 22

Whenever the door of hell opens, the voice you hear is your own

—Philip Wylie

Generation of Vipers

Mantled with a smooth sheen of snow, decorated with tinsel and giant plastic candy canes and strings of colored lights, the tiny mountain village looked both idyllic and vaguely fraudulent, like a movie set carefully erected for a remake of

White Christmas.

The dark, winter-afternoon sky was pregnant with more snow, and squares of amber shone warmly in most of the frame and false-fronted buildings; despite the energy crisis, the bulbs strung across Sierra Street burned in steady hues. On the steep valley slopes to the west, south and east, the red fir and lodgepole pine forests were shadowed, white-garbed, and as oddly unreal as the village itself.

A car with its headlamps on came down through the long, cliff-walled pass to the north—County Road 235-A, the only road presently open into or out of the valley—and passed the pine board sign reading: HIDDEN VALLEY ● POPULATION 74 ● ELEVATION 6,033. Just before Garvey’s Shell, where the county road became Sierra Street, the car moved slowly beneath the spanning Christmas decorations, past the Valley Café and Hughes’ Mercantile and the Valley Inn and Tribucci Bros. Sport Shop. When it reached the All Faiths Church, at the end of the three-block main street, it turned into the fronting lot and then swung around to the small cottage at the rear: the Reverend Peter Keyes, home from the larger town of Soda Grove, eight miles to the north, where he had relatives.

Diagonally across from the church—beyond the village proper, beyond Alpine Street and the house belonging to retired County Sheriff Lew Coopersmith—was a long, snow-carpeted meadow. In its center a boy and a girl were building a snowman, their breaths making puffs of vapor in the thin, chill air. Traditionally, they used sticks for ears and arms and a carrot for a nose and shiny black stones for vest buttons and eyes and to form a widely smiling mouth. Once they had finished, they stood back several paces and fashioned snowballs and threw them at the man-figure until they succeeded in knocking off its head.

Sierra Street continued on a steady incline for another one hundred and fifty yards and Y-branched then into two narrow roads. The left fork was Macklin Lake Road, which serpentined through the mountains for some fifteen miles and eventually emerged in another adjacent community known as Coldville; deep drifts made it impassable during the winter months. Three miles from the village was the tiny lake which gave the road its name, as well as a large hunting and fishing lodge—closed and deserted now, eight days before Christmas—that catered to spring and summer tourists and to seasonal sportsmen. The right fork, cleared by the town plow after each heavy snowfall, became Mule Deer Lake Road and led to a greater body of water two miles to the southwest, at the rearmost corner of the valley. Near this lake were several summer homes and cabins, as well as three year-round residences.

The third valley road was Lassen Drive. It began in the village, two blocks west of Sierra Street, extended in a gradual curve a mile and a half up the east slope, and then thinned out into a series of hiking paths and nature trails. Hidden Valley’s largest home was located on Lassen Drive, a third of the way up the incline; nestled in thick pine, but with a clear view of the village and the southern and western slopes, it was a two-storied rustic with an alpine roof and a jutting, Swiss-style veranda. Matt Hughes, the mayor of Hidden Valley and the owner of Hughes’ Mercantile, lived there with his wife, Rebecca.

Five hundred yards above was a small A-frame cabin, also nestled in pine, also with a clear view, also belonging to Matt Hughes. Neither the Hugheses nor any of the other residents of Hidden Valley knew much about the man who had leased the cabin late the previous summer—the man whose name was Zachary Cain. They had no idea where he had come from (other than it might have been San Francisco) or what he did for a living or why he had chosen to reside in this isolated valley high in the northwestern region of California’s Sierra Nevada; he offered no information, he was totally reticent and unknowable. All they knew for certain was that he never left the valley, ventured into the village only to buy food and liquor, received a single piece of mail every month and that a cashier’s check for three hundred dollars, drawn on a San Francisco bank, which he cashed at the Mercantile. Some said, because of the quantity of liquor he bought and apparently consumed each week, that he was an alcoholic recluse. Others believed he was an asocial and independently well-off eccentric. Still others thought he was in hiding, that maybe he was a fugitive of one type or another, and this had caused some consternation on the part of a small minority of residents; but when Lew Coopersmith, on the urging of Valley Café owner Frank McNeil, checked Cain’s name and description through the offices of the county sheriff, he learned enough to be sure that Cain was not wanted by any law enforcement agency—and then dropped the matter, because it would have been an invasion of privacy to pursue it further. As a result, the villagers finally, if somewhat grudgingly, accepted Cain’s presence among them and left him for the most part strictly alone.

Which was, of course, exactly the way he wanted it.

He sat now, as he often did, at the table by the cabin’s front window, looking down on Hidden Valley. He was a big, dark man with thick-fingered hands that gave the impression of power and, curiously, gentleness. The same odd mixture was in the long, squarish cast of his face and had once been in his bar-browed gray eyes, but the eyes now were haunted, filled with emptiness, like old old houses which had been abandoned by their owners. Brown-black hair grew thickly, almost furlike, on his scalp and arms and hands and fingers, giving him a faintly but not unpleasantly bearish appearance. The image was enhanced by the gray-flecked beard he had grown five months earlier for the simple reason that he no longer cared to continue the daily ritual of shaving. The waxy look of the skin pulled taut across his cheekbones and beneath his eyes added ten false years to his age of thirty-four.

The cabin had two rooms and a bath, with knotty pine walls and thick beams that crisscrossed the high, peaked ceiling. It was furnished spartanly: in the living room, a small stone fireplace, a settee with cushions upholstered in material the color of autumn leaves, a matching chair, a short waist-high pine breakfast counter behind which were cramped kitchen facilities; in the bedroom, visible through an open door on the far side of the room, an unmade bed and a dresser and a curve-backed wicker chair. There were no individual, homelike touches anywhere—no photographs or books or paintings or masculine embellishments of any kind; the cabin was still the same impersonal tourist and hunters’ accommodation it had been when he leased it.