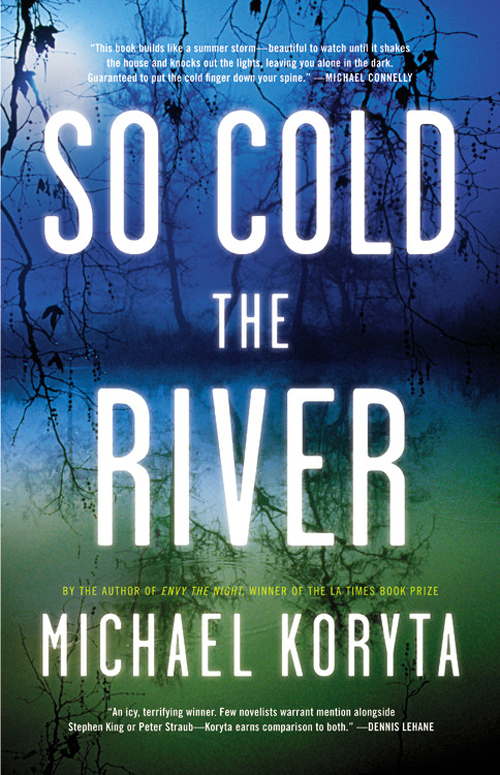

So Cold the River (2010)

Read So Cold the River (2010) Online

Authors: Michael Koryta

Contents

PART THREE: A SONG FOR THE DEAD

A Preview of

Michael Koryta’s The Cypress House

The Silent Hour

Envy the Night

A Welcome Grave

Sorrow’s Anthem

Tonight I Said Goodbye

Copyright © 2010 by Michael Koryta

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.hachettebookgroup.com

First eBook Edition: June 2010

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette

Book Group, Inc.

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and

not intended by the author.

ISBN: 978-0-316-08859-6

For Christine, who wouldn’t let me talk myself out of this one

CURER OF ILLS

1

Y

OU LOOKED FOR THE

artifacts of their ambition. That was what a sociology professor had said one day in a freshman seminar, and Eric Shaw had

liked something about the phrase, wrote it and only it in a notebook that would soon be forgotten and then discarded.

Artifacts of their ambition.

Only through study of those things could you truly understand people long departed. General artifacts could be overanalyzed,

layered with undue importance. It was critical to find things that indicated ambitions and aspirations, that tired bit about

hopes and dreams. The reality of someone’s heart lay in the objects of their desires. Whether those things were achieved did

not matter nearly so much as what they had been.

The phrase returned to Eric almost two decades later as he prepared a video montage for a dead woman’s memorial service.

Video life portraits,

that’s what he called them, an attempt to lend some credibility to what was essentially a glorified slide show.

There’d been a time when neither Eric nor anyone who knew him would have been able to believe this sort of career lay ahead

for him. He still had trouble believing it, in fact. You could live a life and never comprehend exactly how you found yourself

in it. Hell of a thing.

If he were fresh out of film school, he might have been able to convince himself that this was merely part of the artist’s

struggle, a way to pay the bills before that first big break. Truth was, it had been twelve years since Eric claimed his film

school’s highest honor,

twelve years

. Two years since he’d moved to Chicago to escape the train wreck of his time in L.A.

During his peak, thirty years old and landing bigger jobs with regularity, his cinematography had been publicly praised by

one of the most successful movie directors in the world. Now Eric made videos for graduations and weddings, birthdays and

anniversaries. And funerals. Lots of funerals. That had somehow become his niche. Word of mouth sustained a business like

his, and the word of mouth about Eric seemed to focus on funerals. His clients were generally pleased by his videos, but the

funeral parties were elated. Maybe on some subconscious level he was more motivated when his work concerned the dead. There

was a greater burden of responsibility there. Truth be told, he operated more instinctively when he prepared a memorial video

than when he did anything else. There seemed to be a muse working then, some innate guiding sense that was almost always right.

Today, standing outside a suburban funeral parlor with a service about to commence, he felt an unusual sense of anticipation.

He’d spent all of the previous day—fifteen hours straight—preparing this piece, a rush job for the family of a forty-four-year-old

woman who’d been killed in a car accident on the Dan Ryan Expressway. They’d turned over photo albums and scrapbooks and select

keepsakes, and he’d gotten to work

arranging images and creating a sound track. He took pictures of pictures and blended those with home video clips and then

rolled it all together and put it to music and tried to give some sense of a life. Generally the crowd would weep and occasionally

they would laugh and always they would murmur and shake their heads at forgotten moments and treasured memories. Then they’d

take Eric’s hand and thank him and marvel at how he’d gotten it just right.

Eric didn’t always attend the services, but Eve Harrelson’s family had asked him to do so today and he was glad to say yes.

He wanted to see the audience reaction to this one.

It had started the previous day in his apartment on Dearborn as he was sitting on the floor, his back against the couch and

the collection of Eve Harrelson’s personal effects surrounding him, sorting and studying and selecting. At some point in that

process, the old phrase came back to him, the

artifacts of their ambition,

and he’d thought again that it had a nice sound. Then, with the phrase as a tepid motivator, he’d gone back through an already

reviewed stack of photographs, thinking that he had to find some hint of Eve Harrelson’s dreams.

The photographs were the monotonous sort, really—everybody posed and smiling too big or trying too hard to look carefree and

indifferent. In fact, the entire Harrelson collection was bland. They’d been a photo family, not a video family, and that

was a bad start. Video cameras gave you motion and voice and spirit. You could create the same sense with still photographs,

but it was harder, certainly, and the Harrelson albums weren’t promising.

He’d been planning to focus the presentation around Eve’s children—a counterintuitive move but one he thought would work well.

The children were her legacy, after all, guaranteed to strike a chord with family and friends. But as he sorted through

the stack of loose photographs, he stopped abruptly on a picture of a red cottage. There was no person in the shot, just an

A-frame cottage painted a deep burgundy. The windows were bathed in shadow, nothing of the interior visible. Pine trees bordered

it on both sides, but the framing was so tight there was no clear indication of what else was nearby. As he stared at the

picture, Eric became convinced that the cottage faced a lake. There was nothing to suggest that, but he was sure of it. It

was on a lake, and if you could expand the frame, you’d see there were autumn leaves bursting into color beyond the pines,

their shades reflecting on the surface of choppy, wind-blown water.

This place had mattered to Eve Harrelson. Mattered deeply. The longer he held the photograph, the stronger that conviction

grew. He felt a prickle along his arms and at the base of his neck and thought,

She made love here

.

And not to her husband.

It was a crazy idea. He pushed the picture back into the stack and moved on and later, after going through several hundred

photographs, confirmed that there was only one of the cottage. Clearly, the place hadn’t been that special; you didn’t take

just one picture of a place that you loved.

Nine hours of frustration later, nothing about the project coming together the way he wanted, Eric found the photo back in

his hand, the same deep certainty in his brain. The cottage was special. The cottage was sacred. And so he included it, this

lone shot of an empty building, worked it into the mix and felt the whole presentation come together as if the photograph

were the keystone.

Now it was time to play the video, the first time anyone from the family would see it, and while Eric told himself his curiosity

was general—you always wanted to know what your clients thought of your work—in the back of his mind it came down to just

one photograph.

He entered the room ten minutes before the service was to begin, took his place in the back beside the DVD player and projector.

Thanks to a Xanax and an Inderal, he felt mellow and detached. He’d assured his new doctor that he needed the prescriptions

only because of a general sense of stress since Claire left, but the truth was he took the pills anytime he had to show his

work. Professional nerves, he liked to think. Too bad he hadn’t had such nerves back when he’d made real films. It was the

ever-present sense of failure that made the pills necessary, the cold touch of shame.

Eve Harrelson’s husband, Blake, a stern-faced man with thick dark hair and bifocals, took the podium first. The couple’s children

sat in the front row. Eric tried not to focus on them. He was never comfortable putting together a piece like this when there

were children to watch it.

Blake Harrelson said a few words of thanks to those in attendance, and then announced that they would begin with a short tribute

film. He did not name Eric or even indicate him, just nodded at a man by the light switch when he stepped aside.

Showtime,

Eric thought as the lights went off, and he pressed play. The projector had already been focused and adjusted, and the screen

filled with a close-up of Eve and her children. He’d opened with some lighthearted shots—that was always the way to go at

a heavy event like this—and the accompanying music immediately got a few titters of appreciative laughter. Amidst the handful

of favorite CDs her family had provided, Eric had found a recording of Eve playing the piano while her daughter sang for some

music recital, the timing off from the beginning and getting worse, and in the middle you could hear them both fighting laughter.

It went on like that for a few minutes, scattered laughter and some tears and a few shoulder squeezes with whispered words

of

comfort. Eric stood and watched and silently thanked whatever chemist had come up with the calming drugs in his bloodstream.

If there was a more intense sort of pressure than watching a grieving group like this take in your film, he couldn’t imagine

what it was. Oh, wait, yes he could—making a real film. That had been pressure, too. And he’d folded under it.

The cottage shot was six minutes and ten seconds into the nine-minute piece. He’d kept most pictures in the frame for no more

than five seconds, but he’d given the cottage twice that. That’s how curious he was for the reaction.

The song changed a few seconds before the cottage appeared, cut from an upbeat Queen number—Eve Harrelson’s favorite band—to

Ryan Adams covering the Oasis song “Wonderwall.” The family had given Eric the Oasis album, another of Eve’s favorites, but

he’d replaced their version with the Adams cover during his final edit. It was slower, sadder, more haunting. It was right.

For the first few seconds he could detect no reaction. He stood scanning the crowd and saw no real interest in their faces,

only patience or, in a few cases, confusion. Then, just before the picture changed, his eyes fell on a blond woman in a black

dress at the end of the third row. She’d turned completely around and was staring back into the harsh light of the projector,

searching for him. Something in her gaze made him shift to the side, behind the light. The frame changed and the music went

with it and still she stared. Then the man beside her said something and touched her arm and she turned back to the screen,

turned reluctantly. Eric let out his breath, felt that tightness in his neck again. He wasn’t crazy. There was something about

that picture.