So Many Roads (9 page)

Authors: David Browne

Lesh was soon gone from the scene; dropping out of the University of California at Berkeley, he wound up living with Constanten and his

family in Las Vegas during the summer of 1962. (In between, he and Constanten signed up for composer Luciano Berio's composition class at Mills College in Oakland, which also fostered their mutual love of adventurous music.) Constanten's parents took issue with Leshâwho, by then, was letting his hair grow outâand asked him to leave, although Constanten says he never understood what happened: “They would yell at me, and I never knew what I did,” he says. “It was a very old-world sort of thing.” Either way, Lesh wound up taking a job at the post office in Vegas, hoping to work his way back to Palo Alto when he could.

But that night on the

Midnight Special

show Lesh didn't simply have another chance to observe Garcia's musical prowess; he also noticed the way Garcia effortlessly bantered with Chiarito, whom everyone knew was no pushover. “She had a lot of local folkies kissing her ass, and Jerry didn't do that,” Lesh says. “He was just himself. I was watching him win her over instantaneously.” Few others in their world, Lesh included, had those types of people skills at that point in their lives, yet Garcia already seemed to have mastered it. As Leicester would later tell Hajdu, Garcia was “a kind of natural bohemian, but he was a bohemian who knew how to find his way through the establishment. He had the ability to make people like him and get done what he wanted to do.” That ability to subvert from within would become increasingly useful as the years went by.

As dusk approached, Garcia and Meier sang “Go Down, Old Hannah” a few more times. Eventually the sun set, and they were still alive.

The two didn't know it at the timeâin the days before the Internet and twenty-four-hour cable news, few did immediatelyâbut Kennedy and Khrushchev had already defused the situation with Cuba. At almost the same time the couple had climbed their hill, at 8:05 p.m. Eastern time, (5:05 p.m. Pacific time) Kennedy had offered a deal to

Khrushchev: in a telegram he asserted that the Soviet Union “would agree to remove these weapons systems from Cuba under appropriate United Nations observation and supervision; and undertake, with suitable safeguards, to halt the further introduction of such weapons systems into Cuba,” while the United States would vow not to invade Cuba. (The United States would also remove its missiles from Turkey.) The Peninsula hadn't been scorched by a nuclear mushroom cloud; the grass around them was still golden.

Garcia and Meier began making their way down the hill and back to their homes. When she arrived at her parents' house late that night, Meier's parents made her dinner and told her they'd been worried sick, and her mother hugged her.

For Garcia, who'd been deeply affected after reading George Orwell's

1984

in grade school, the incident was yet another reminder that the establishment, especially the government, couldn't be trusted. The mere thought that the world had almost ended over a macho showdown between two heads of state felt absurd to both him and Meier. A few years later, with the band that would finally make him more famous than he probably wanted to be, he would begin singing “Morning Dew,” Bonnie Dobson's elliptical but haunting ballad about life after nuclear fallout, inspired by the novel (and movie)

On the Beach

. The song had a mournful and resigned tone to start with, even when pop star Lulu covered it later, but Garcia brought to its lyrics a palpable ache, stretching out some of the notes as if he were digging deep into that spooked side of himself and his past.

The Cuban Missile Crisis was also another reminder of the fragility and impermanence of the world. The planet hadn't ended, but just as with the death of his father and Speegle, Garcia's world could have been tossed on its head in a heartbeat. “It was the beginning of us realizing that there were forces that could whisk away the people you love and the whole freaking planet,” Meier says. “With the Cold War that

became an ongoing subliminal message, which is probably one reason why Jerry never made any plans.” Years later, after she had reconnected with him, Meier would wonder about the impact of that night on Garcia's later bad habits, as well as the culture of the Grateful Dead itself. The message couldn't have been less ambiguous: it was best to live in the moment, do whatever one wanted, and find pleasure in it because that moment could be taken away at any time.

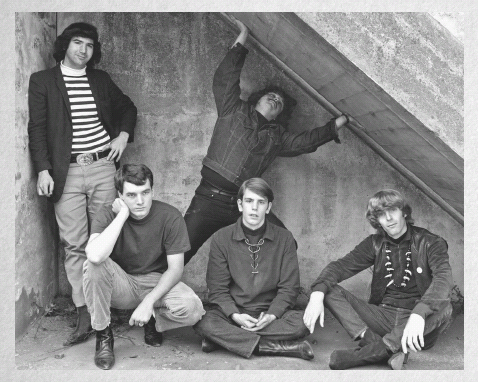

The Warlocks, 1965: Garcia and McKernan (top row), Kreutzmann, Weir, and Lesh (seated).

© HERB GREENE

MENLO PARK, CALIFORNIA, MAY 26, 1965

It was pretty much the last place anyone expected to find a rock 'n' roll band. Jammed between local business stores on Menlo Park's main shopping drag, Magoo's was a pizza parlor, not a nightclub or bar. It didn't look all that different from the thousands that had popped up around the country after World War II, when American soldiers returning from Europe talked up the delicious bread, tomato sauce, and cheese concoctions they'd wolfed down in Italy. Most of the American pizza chains and restaurants bore a resemblance to Magoo'sâlong and narrow, picnic-style benches lined along the wall up front, a counter and oven to the right, florescent lighting overhead. But in a town teeming with college and high school students yearning for places to bond, Magoo's was a gathering place for the emerging tribe.

On this Wednesday night the young band making a clanging racket inside was as idiosyncratic as the setting. The lead guitarist now had a helmet head of thick, curly hair; his goatee had been banished for the

time being to his bluegrass days. Hunched over a portable Vox organ was a stocky kid with an equally unkempt mop, a spotty complexion, and a truculent gaze that dared anyone to mess with him. (The hair on both looked like it had been smushed down on their heads.) The other threeâthe drummer, the bass player, and especially the rhythm guitarist, so young looking he could easily have been on a middle school night outâappeared straighter and not quite as grubby. The sound they were making, bouncing off Magoo's brick walls, was a clattering, exuberant, but not fully shaped mash-up of blues, jug band, rock 'n' roll, and R&B. “They were still searching for their own sound,” recalls John McLaughlin, who'd taken percussion lessons from the Warlocks' drummer, Bill Kreutzmann. “I thought, âThis is weird stuff.' Most of the local bands sounded like the Beatles or the Stones. The Warlocks sounded like music from the first

Star Wars

, when Luke Skywalker walks into the bar and they're playing reverse jazz. It sounded really strange.”

The first time the Warlocks had set up musical shop at Magoo's, three weeks earlier, a small group of friends had shown up along with a smattering of high school kids they'd enticed. “It wasn't too hard to get the student population to come hear music,” says one of those friends, Palo Alto High School student Connie Bonner (later Bonner Mosley). “It was perfect timing: âCome over after school to Magoo'sâhave a pizza!' They all came.” It almost didn't matter how the band sounded; with rock 'n' roll experiencing a heady, joyful rebirth, the

idea

of the Warlocks would be enticing enough.

That first night at Magoo's, May 5, the Warlocks' lack of experienceâthe second guitarist, Bob Weir, had barely even held an electric guitar beforeâbecame amusingly apparent when they started playing. Some of them sat on stools, staring at each other instead of at the small crowd gathered in front of them. Bonner and her friend Sue Swanson, who'd become the band's first two loyal fans, the original Deadheads, called upon their extensive knowledge of the Beatles' stage craft and

went over and offered the Warlocks advice: leave the stools, stand up, turn around, make eye contact. They were playing

rock 'n' roll

now, not bluegrass or jug-band music, and the songs required more visceral skills. The musicians, especially the lead guitarist, Weir's older buddy Garcia, seemed thankful for the suggestions. After all, what did

they

know about doing this? Tonight's show had at least one slightly wholesome touch: because it was Swanson's seventeenth birthday, her mother, much to her daughter's embarrassment, showed up with a cake.

With each of the Warlocks' weekly Wednesday shows that followed, Magoo's grew a bit more congested, the crowd eventually spilling out onto the sidewalk on Santa Cruz Avenue. (Granted, it took only a few dozen people to do that, but it certainly looked impressive to anyone passing by.) Sometimes the Warlocks played in a corner in the back; other nights, like tonight, they were jammed into a space near the front window. Earlier, the local fire marshal had dropped by and been concerned about the overflow crowd. (Although May 27 has often been cited as the day of the Warlocks' third Magoo's show, that was a Thursday, so May 26 is likely the correct date.)

Among Garcia's musician friends word had spread that he was secretly venturing into electric rock 'n' roll. Some of his bluegrass-inclined buddies were dismayed, but another acquaintance outside that circle was curious to hear the makeover. As the band played that night Phil Lesh and his girlfriend, Ruth Pakhala, walked through the front door. Lesh had tried to see the Warlocks before at Magoo's but had shown up so late that he'd only been able to join in on after-show party elsewhere. There he, Weir, and Garcia shared an ample stash of pot. Tonight, though, the couple had arrived on time.

By then a thought had been buzzing around in Garcia's brain. He knew the bass player, Dana Morgan Jr., wasn't cutting it: he was too square, too straight, too disinterested in getting stoned. The Warlocks needed someone more like them: adventurous, hard-headed, a little

wild. As the band took a short breakâand partook of the free beer and pizza the owners of Magoo's offered in lieu of payâGarcia put down his guitar and made a beeline for Lesh.