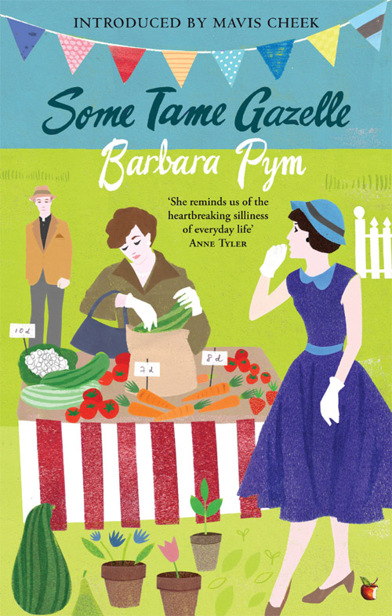

Some Tame Gazelle

Authors: Barbara Pym

VIRAGO

MODERN CLASSICS

541

Barbara Pym

Barbara Pym (1913–1980) was born in Oswestry, Shropshire. She was educated at Huyton College, Liverpool, and St Hilda’s College, Oxford, where she gained an Honours Degree in English Language and Literature. During the war she served in the WRNS in Britain and Naples. From 1958–1974 she worked as an editorial secretary at the International African Institute. Her first novel,

Some Tame Gazelle

, was published in 1950, and was followed by

Excellent Women

(1952),

Jane and Prudence

(1953),

Less than Angels

(1955),

A Glass of Blessings

(1958) and

No Fond Return of Love

(1961).

During the sixties and early seventies her writing suffered a partial eclipse and, discouraged, she concentrated on her work for the International African Institute, from which she retired in 1974 to live in Oxfordshire. A renaissance in her fortunes came in 1977, when both Philip Larkin and Lord David Cecil chose her as one of the most under-rated novelists of the century. With astonishing speed, she emerged, after sixteen years of obscurity, to almost instant fame and recognition.

Quartet in Autumn

was published in 1977 and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize.

The Sweet Dove Died

followed in 1978, and

A Few Green Leaves

was published posthumously. Barbara Pym died in January 1980.

Excellent Women

Jane and Prudence

Less than Angels

A Glass of Blessings

No Fond Return of Love

Quartet in Autumn

The Sweet Dove Died

A Few Green Leaves

Crampton Hodnet

An Unsuitable Attachment

An Academic Question

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 9780748131525

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © Barbara Pym 1950

Introduction copyright © Mavis Cheek 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

Contents

From the opening line of

Some Tame Gazelle

you are safely and deliciously in Pym Country. ‘The new curate seemed quite a nice young man, but what a pity it was that his combinations showed, tucked carelessly into his socks.’ The curate in question is visiting Belinda and Harriet Bede, unmarried, middle-aged sisters living in the heart of a village parish. Plump Harriet likes to tuck young, pale, thin curates under her substantial wing, while the more circumspect Belinda potters through her life, comfortably loving the Archdeacon from afar.

Harriet is much more flamboyant than her sister, and given to wearing fashionable frocks in which she is well buoyed up by corsets. (Barbara Pym is awfully good at writing about clothes.) These corsets, under constant strain, frequently need mending, and are often to be found thrust beneath a cushion when an unexpected visitor comes to call. Harriet is loved, unrequitedly, by an adoring Italian count who asks for her hand in marriage on a regular basis and which, on a regular basis, is declined. Both seem quite content with this.

Belinda, who little cares for fashion, asks for nothing more than to continue to adore the handsome, self-satisfied Archdeacon from afar, and to loyally support him as he bemoans the heavy workload of his parish duties which, in fact, are mostly absorbed by said pale, young curates. It is Belinda’s task and delight, she feels, to support and explain the Archdeacon’s sermons, which are often of great length, and totally obscure. Here, one of the Pym trademarks is used to great effect – the sharp and skilful quoting of poetry and various texts. Barbara was extraordinarily well-read and could find the perfect quotation for any occasion. Robert ‘Jock’ Liddell wrote that she had ‘a genius for quotation which has probably never been equalled’. When the Archdeacon finishes a particularly long and unintelligible sermon, she has him quote Edward Young (a poet also known for his somewhat lengthy and disconnected texts):

Say dreamers of gay dreams,

How will you weather an eternal night,

Where such expedients fail?

The bored congregation, she says, ‘had been dreaming gay dreams most of the morning … and had only allowed their thoughts to wander when it had passed beyond their comprehension.’

Belinda often compares herself, unfavourably, to Archdeacon Hoccleve’s capable and more literary wife. Agatha is cool, elegant, and unsympathetic. She is the kind of woman who is a glad martyr to her rheumatism, and takes the waters at Karlsbad for her holidays. And she is based on someone Barbara knew and disliked at Oxford. This is another of Barbara Pym’s authorial characteristics: she loved to include real people in her books. Even the sisters, Harriet and Belinda, are loosely based on herself and Hilary, her elder sister. When she began writing

Some Tame Gazelle

in 1934, at the astonishingly young age of twenty-one, she imagined them both, she said in her diary, ‘as spinsters of fiftyish’.

Barbara was a great one for falling in and out of love as often, and usually as hopelessly, as possible – and a great one for using her experiences in her books. Archdeacon Hoccleve is also based on a real person, an old flame who rejected Barbara at Oxford. One can only wonder on whom the famous librarian, Nathaniel Mold, and the visiting bishop from Africa, Theodore Grote, are based when they make their unsettling and unwelcome visits to each of the sisters in turn. The sense of glee she shows in the writing of these characters is practically palpable. Beware! Thus fall all miscreants in a sharp-eyed novelist’s life – eventually.

High comedy the book may be but perhaps one of her greatest gifts as a novelist is that she puts her own hand up to the frailties and foibles, the affectations and absurdities that her characters contain and endure. As with all the best writers of comedy, she is non-judgemental and, though beady-eyed, she is also sympathetic, particularly in matters of the heart and how foolishly they can make us behave. From the very first she proved herself to be an accomplished novelist of sharply observed comedies of manners where, though life appears to be carrying on calmly and evenly, beneath its façade lie dark undercurrents, hidden desires and unsuitable attachments.

Barbara wrote in her diary that she ‘

must

work at my novel, that is the only thing there is and the only way to find any happiness at present … I want

Liebe

but I would be satisfied if my novel could be published.’ That novel was

Some Tame Gazelle

, and it set the pattern for all the rest.

Some tame gazelle, or some gentle dove:

Something to love, oh, something to love!

After many drafts

Some Tame Gazelle

was finally published by Jonathan Cape in 1950. Her friend from Oxford, Jock Liddell, who read it in its first incarnation and in its last before she offered it to publishers said, ‘The wonderful thing is that you haven’t spoiled it – it is still the book we knew and loved – and yet it is tidy and shapely, and every blot removed.’

It was received with ecstatic reviews. The

Observer

said, ‘She creates a small well-bred Eden, but contrives to insert a little old Adam as well.’ The

Daily Telegraph

wrote, ‘Miss Pym’s sharp fresh fun is all her own’, while the

Manchester Guardian

called it ‘An enchanting book about village life, but no more to be described than a delicious taste or smell.’ And the

Church Times

, which might be expected to be a little sour, given the harsh light her books shone upon the life and ways of the clergy, had nothing but praise for it: ‘We needn’t bring Jane Austen into it, but Miss Pym is writing in a great tradition and she knows it.’ Yes, she most certainly does. She knows exactly how to take a small community of folk and make its story timeless, universal and very, very funny.

Barbara went on to publish a further five critically well-received novels before, in 1963, with quite extraordinary lack of foresight, Cape’s Tom Maschler refused to publish her next,

An Unsuitable Attachment

. Many years later she wrote to Philip Larkin that she and her sister Hilary had invented a pudding which they called ‘a Maschler – a sort of milky jelly’ – which is just the kind of thing that might happen in a Barbara Pym novel.

When Philip Larkin, perhaps Barbara’s greatest fan and champion, discovered that Cape had rejected her, he was outraged at the Maschler decision, writing to her that:

I can’t understand why the publishers are taking this line … it seems a sad state of affairs if such tender, perceptive and intelligent work can’t see the light, just because some tasteless chump thinks it won’t ‘go’ in paperback.

Suffice it to say that when

An Unsuitable Attachment

did get published, posthumously in 1982, it was received with rave reviews.

But to begin at the beginning … For those readers who have yet to discover Miss Barbara Pym, this debut novel will be full of delights and surprises; for those of us who have read and loved her books for years, this new edition of the first of her novels is a fitting tribute to her brilliant, humorous story-telling and the enduring charm of her writer’s eye.

Some Tame Gazelle

is still my personal favourite for its sparkling high comedy and its treasury of characters, but rereading the entire canon, ten novels in all, has been pure bliss. She makes me smile, laugh out loud, consider my own foibles and fantasies, and, above all, suffer real regret when I reach the final page. Of how many authors can you honestly say that?

Mavis Cheek

November 2008