Sons and Daughters

Read Sons and Daughters Online

Authors: Mary Jane Staples

By the year 1949, life in Walworth has almost returned to normal. Sammy and Boots, now in a highly successful partnership, are rebuilding the old family firm. But an old enemy resurfaces – Mr Ben Ford, better known as the Fat Man, who seems determined to ruin the various branches of this growing business. It takes all the well-known Adams ingenuity and determination to outwit the thugs in the Fat Man’s pay.

Meanwhile, an attractive blonde woman shopping in the market has caught Boots’s eye. But Polly does not need to feel apprehensive – the sight of this woman has stirred the worst of memories for Boots, from the darkest days of the war. And on a happier note, there is some surprising news for Chinese Lady – news which will affect the whole of the Adams family.

SONS AND

DAUGHTERS

Mary Jane Staples

1949

Millions of people displaced by man’s inhumanity to man during the Second World War had managed, under the aegis of the Allies, to return or be returned to their countries of origin. Stalin’s armies had secured the release of two million Russian prisoners of war, most of whom his police had arrested, tortured and either murdered or despatched to Siberia to die of starvation and freezing cold, on the grounds that they should never have surrendered in the first place.

Jewish and other survivors of the death camps had been resettled in Palestine, or returned home according to their wishes, while the whole world tried to take in unbelievable accounts relating to the purpose and use of Nazi gas chambers and crematoria.

Slave labourers from every country invaded and occupied by the Germans had perished by the thousands in the appalling conditions forced on them by the sadists of Hitler’s war factories. Those

who survived had gradually found their way home.

Many Nazi war criminals of the SS had avoided capture and used a prearranged escape route to reach safety in South America or anti-Semitic Middle East states. Or elsewhere.

In the UK, a number of men and women who had served in General Sikorski’s Free Polish Army refused to be returned to Poland, since it was now one of Stalin’s post-war puppet states. These particular Poles applied for permanent residence in Britain, and received it. And, surprisingly, so did some German prisoners of war, mostly of the staunch anti-Nazi calibre, who were disgusted by all that they had come to know of Himmler’s atrocious SS and its murderous ideology.

These Poles and Germans settled down to life in Britain. So, it was rumoured, did a few undetected war criminals.

With the return home of the men and women of the Armed Forces, the people of the UK seized the chance to rebuild their lives. Families split and unsettled by the demands and circumstances of the war made the effort to resume normal life.

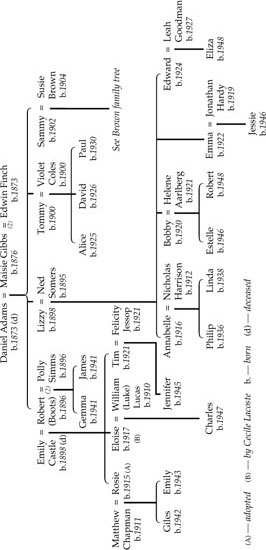

The families relating to Mrs Maisie Finch went about the pleasure of reunion with typical enthusiasm. Marriages that had been blessed by the arrival of children during the war were followed by post-war marriages and births. In the third year of the war, Boots and Polly had become the parents of twins, Gemma and James. And in 1945, Felicity, the blind wife of Tim, had had a baby girl, Jennifer.

Post-war, a girl, Estelle, and a boy, Robert, had been born to Bobby and Helene Somers. Bobby’s brother Edward and wife Leah had brought forth a girl, Eliza. Sammy Adams’s son Daniel, married to Patsy from America, was presented with a girl, Arabella. Boots’s French daughter, Eloise, and her husband, Colonel Lucas, had a boy, Charles. And Emma and Jonathan had a girl, Jessie.

With the advent of 1949, life was in full swing for Mrs Maisie Finch and her extensive family.

Late July, 1949

The day was breezy, the sky above London a pattern of swirling white clouds against the canopy of blue. The cockneys might have admired the picturesque look of such a sky if they hadn’t known July clouds could turn as spiteful as April’s and drop heavy showers on them.

It was midday Saturday, and in Walworth’s East Street market a flowing tide of shoppers surged around the stalls. The war had been over for four years, and while some foods were still rationed, home-grown produce was up to the mark in quality and quantity, and imported fruit was beginning to add colour and choice to laden stalls.

A well-dressed man, whose stylish grey trilby was worn at a dashing angle, was moving from stall to stall, pausing to say hello to stallholders he had come to know years ago. The responses were of a typical cockney kind.

‘Well, if it ain’t Mister Bleedin’ Sammy Adams ’imself in a Sunday suit. How yer doing, Sammy?’

‘Still standing up,’ said Sammy.

From another stallholder, ‘Blimey O’Reilly, ain’t seen you in years, Sammy old cock. Thought Hitler had got yer with his bombs.’

‘Well, he tried, believe me he did,’ said Sammy. ‘He dropped one straight through the roof of the family castle, and it fell down. Fortunately, no-one was in it at the time, including me.’

It was an excursion into the old and familiar for Sammy, who had left his office early to visit the market. He was now forty-seven, but still a fine figure of a bloke with electric blue eyes that could make some ladies feel he could see more than was good for him. Sharp as a needle, but with an unfailing sense of humour, his exchanges were lively with the men and women he had known since he himself had been a stallholder. Sammy had a long memory for good turns done and friends made in true and hearty cockney fashion during his struggling years. Although some faces were missing, he liked the fact that those who’d survived the war had kept their stalls going. They were all older than he was, but still sturdy on their feet, still offering bargains to the people of Walworth and the kind of competition that made Walworth Road shop prices look a bit over the top.

Down near the middle of the market was a stall that specialized in quality fruit and vegetables, the prices always a little more per pound than elsewhere, but the quality guaranteed. The woman running it looked up into the face of her next customer. She blinked.

‘Well, bless me old plates of meat,’ she said, ‘is that you, Boots?’

Robert Adams, known as Boots, smiled. Just fifty-three, he was a distinctive figure in his Norfolk jacket, light grey trousers and tweed hat. He had served in both world wars, but neither had soured him. His whimsical nature, his interest in life and people, and his love for his family were always evident. If age could not weary those who had fallen, neither did it yet sit tiredly on survivors like Boots. His wife Polly, who thought him the best of men, also thought it was time he showed his age, since she was sure she herself showed her own. Actually, that was not the case.

‘Hello, Ma,’ said Boots, ‘how are your best pippins?’

One could have said he wasn’t referring to her apples, for Ma Earnshaw was decidedly overflowing and always had been. Still, everyone who knew her agreed that even at her advanced age she made up for the beanpole look of her old man, a retired railway porter who was talking about going to live by the seaside at Southend. Some hopes, said Ma Earnshaw, I’m living and dying at me Walworth stall.

‘Now then, Boots,’ she said, ‘none of yer sauce, I used to get all I needed from yer brother Sammy. How are yer, love, and how’s that Sammy?’

‘He’s around,’ said Boots, ‘he’ll be along to say hello.’

‘I felt for yer fam’ly when the bombs started dropping,’ said Ma Earnshaw. ‘It got around, Boots, that you lost Em’ly.’

‘Damned dark day, Ma, for all of us,’ said Boots.

‘I felt real sad for you, Boots,’ said Ma. ‘Them ’orrible bombs did for others like Em’ly. Mind, I heard from someone that you’d got married again—Here, wait a bit, is that lot yourn?’

‘This lot?’ Boots turned and looked down at three girls and a boy. ‘Well, they’re all family. The two small ones are mine. Gemma and James. Twins by my second wife. The larger ones are Sammy’s, Paula and Phoebe. Say hello to Mrs Earnshaw, young ’uns, she’s an old friend.’

‘Hello.’ The three girls and a boy responded in chorus.

‘Well, ain’t you all a sight for sore eyes?’ smiled Ma, her weathered face creasing benignly.

Paula, fourteen, was fair, slim and skittish. Phoebe, twelve, was dark-haired, dainty, winsome and adopted. The twins were seven but hardly identical, for Gemma owned the dark sienna hair and piquant looks of her mother, while James had his father’s deep grey eyes, dark brown hair and firm features. Each was a bundle of energy, even if at the moment they were shyly quiet under the motherly gaze of Ma Earnshaw.

‘I think they’d all like some oranges,’ said Boots.

‘Well, bless ’em,’ said Ma Earnshaw, ‘and for old times’ sake they can ’ave two each and I couldn’t say fairer.’

‘You could if you’d include two each for their parents,’ said Boots, ‘and two for the girls’ brother Jimmy.’