Spice (45 page)

Authors: Ana Sortun

4 red bell peppers, roasted and peeled (see page 97)

3 tablespoons toasted sesame seeds

1 tablespoon red wine vinegar

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 tablespoon chopped fresh dill

½ teaspoon finely minced garlic (about ½ clove)

1.

Cut each pepper into quarters, removing as many seeds as possible and scraping away any rib on the underside of each piece.

2.

Place the peppers in a small glass mixing bowl and add the rest of the ingredients.

3.

Stir to coat the peppers with the sesame seeds, vinegar, garlic, oil, and dill. Let the mixture sit at room temperature for at least 30 minutes (or up to 1½ hours) and serve.

GOLD AND BOLD

C

URRY

P

OWDER

, T

URMERİC, AND

F

ENUGREEK

The warm, bittersweet, earthy, golden spices in this chapter have similar qualities yet very different flavors, so using them interchangeably is not recommended. I chose to group the three spices together because turmeric and fenugreek are often found in curry powders. Here, “curry” refers to the spice blend and not the leaf or plant, which is also called curry.

Curry spices can brighten up soups or creamy preparations like whipped potatoes or sauces. They also add depth to beef or sausage meats and are wonderful with rich, oily shellfish, fishes, and chicken. Turmeric can be used in small quantities as a coloring agent to intensify the golden colors of corn or yellow tomato; its flavor is subtle enough to lend a background earth tone.

C

URRY

P

OWDER

Curry, which comes from the South Indian word

kari,

meaning “sauce,” is a blend of sweet, hot, and earthy spices that can be mixed in hundreds of different proportions to complement meat, fish, and vegetables. Indian chefs do not use commercial curry powder and neither do Indian families; they grind and create their own blends containing as few as seven or as many as twenty spices. Commercial curry powder was invented and made popular by the British, who sought to replicate the taste of Indian food during the Raj.

Curry powders now spice food all over the world. In the Mediterranean and Portugal, curry is used with a light hand in combination with tomato and fresh herbs like cilantro. Jamaicans use curry powder in meat stews and potato breads. In England, they serve curried egg salad with their afternoon tea. The French whisk curry powder into crème fraîche to finish soups or sauce fish.

A typical Madras-style curry blend may include ground coriander to form the bright flavor base; turmeric for color and earthiness; ginger, black pepper, and chilies to give it zing; and cardamom and cinnamon to add sweetness. By adding different spices, you can change the balance of the curry: allspice or nutmeg will increase sweetness, cumin adds earthiness, mustard or additional chilies increase feistiness, and fennel or bay leaf impart fragrance and more brightness.

I find that curry powder can easily overwhelm the other flavors in a dish, so I like to use it with an extremely light hand and add just the slightest pinch that imparts fragrance. My favorite ways to use curry are with chopped fresh tuna in deviled eggs (page 203) and in tomato-based fish soups like the Portuguese Acorda (page 214). At home, I like to add a pinch to mayonnaise when making egg or chicken salad and to soft butter to eat on radishes fresh from the garden.

Curry powders vary in quality and strength: Madras can be hot, for example, but vindaloo is always very hot. The best curry powders are those you make yourself by toasting, grinding, and mixing spices by hand (see Make Your Own Curry Powder, page 209).

Some commercial brands that you can find in the grocery store—McCormick’s, for example—are acceptable, but they can be chalky because the spices aren’t toasted before grinding. To revive commercial curry powder, toast it for a few minutes in a skillet over low heat while shaking the pan until it gives off a fragrant oil.

I adore the subtlety of the sweet curry powder available at www.penzeys.com. All of the Madras curry powders at www.kalustyans.com are excellent, especially the India spice brand.

T

URMERİC

Turmeric is the orange-yellow rhizome of a tropical plant—similar to ginger but with a rounder bulb—grown chiefly in India, China, and Indonesia. Powdered turmeric is bright yellow and has a distinct, earthy aroma and a pleasing sharp bitterness. It is used to give an earthy depth to curry powders and to color and flavor sauces, prepared mustard, pickles, relish, chutneys, and rice dishes as well as butter and cheese. Turmeric is used widely in North African cooking, as a fish condiment called Charmoula (page 205).

Although turmeric’s bright yellow color is similar to saffron, the two should never be confused, as the flavors differ considerably: saffron is much stronger, acidic, and complicated. Turmeric is also used as a fabric dye, so be careful not to spill any on your clothes; the stains are hard to get out.

There are two main types of turmeric: Alleppey and Madras. Alleppey, which is deeper in color and more flavorful, is the type you’ll find in the spice section of American supermarkets. If you want to try Madras turmeric, visit an Indian grocery store.

F

ENUGREEK

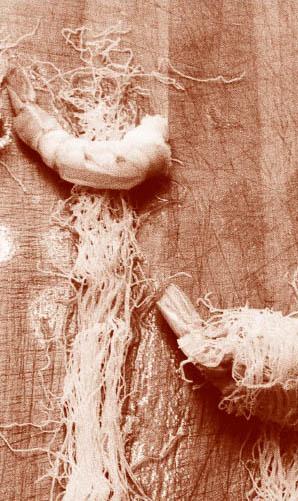

Fenugreek is an annual herb that is a member of the pea family. The seeds look like brown gravel, and they develop in horn-shaped pods that look like miniature broad beans. Fenugreek seeds are often toasted to release their nutty, burnt-sugar flavor, similar to maple syrup (imitation maple sugar is made from fenugreek). Toasting also highlights fenugreek’s bitterness, a coffee or chocolate flavor that is desirable if used in the right proportion in a recipe. The leaves form long tendrils and have a similar flavor to the seeds but lack the underlying bitterness.

Fenugreek is distinctly bittersweet and adds a caramely richness without adding sugar. It’s used in curry powders and in the preparation of eastern Mediterranean charcuterie. It flavors basturma, a pastrami-like dried cured beef that is made in almost every eastern Mediterranean country. It also flavors the

sujuk

(sausage) made by Greeks, Turks, and Armenians.

I’ve become addicted to adding fenugreek to my mashed potatoes (page 216) and homemade mayonnaise for French fries. A “white” platform showcases this spice’s complicated flavors, so fenugreek also goes particularly well with white cheese, cauliflower, and white sauce. In this chapter, I prefer to use fenugreek leaves rather than seeds; I find the flavor to be warmer, grassier, and sweeter and the bitterness easier to control. Fenugreek has a very strong flavor, so use a careful hand. Too much of it—especially the ground seed—can make a dish bitter and inedible.

You can find fenugreek leaves at Indian markets or Middle Eastern stores, or you can get them online at www.kalustyans.com. To make fenugreek powder, push the leaves through a medium-fine sieve over a small mixing bowl, crushing them and removing bits of stem.

RECIPES WITH CURRY, TURMERIC, AND FENUGREEK

H

OT

B

UTTERED

H

UMMUS WİTH

B

ASTURMA AND

T

OMATO

D

EVİLED

E

GGS WİTH

T

UNA AND

B

LACK

O

LİVES

S

HRİMP WİTH

K

ASSERİ

C

HEESE

, F

ENNEL, AND

F

ENUGREEK

W

RAPPED İN

S

HREDDED

P

HYLLO

F

ANNY

’

S

F

RESH

P

EA AND

T

WO

P

OTATO

S

OUP

A

CORDA

: P

ORTUGUESE

B

READ

S

OUP WİTH

R

OCK

S

HRİMP

R

OAST

C

HİCKEN

S

TUFFED WİTH

B

ASTURMA AND

K

ASSERİ

C

HEESE

Hot Buttered Hummus with Basturma and Tomato

This recipe was inspired by my trip to Cappadocia, in the center of Turkey, where I saw the most incredible phallic natural rock formations. These “fairy chimneys” are volcanic deposits that have been sculpted by wind and rain. Cappadocia is also known for its

manti

—very small raviolis—and its kasseri cheese and thriving dairy farms. In Cappadocia, they make hummus without tahini, and they use butter instead of olive oil because of its quality and availability. I lighten this recipe by using half butter and half olive oil. The butter pairs well with the spicy beef, and the olive oil imparts the Mediterranean flavor.