Spider Light

PIDER

L

IGHT

Roots of Evil

A Dark Dividing

Tower of Silence

Visit www.sarahrayne.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2006

This edition published by Pocket Books, 2007

An imprint of Simon & Schuster UK

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright © Sarah Rayne, 2006

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

® and © 1997 Simon & Schuster Inc. All rights reserved.

The right of Sarah Rayne to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

Africa House

64–78 Kingsway

London WC2B 6AH

Simon & Schuster Australia

Sydney

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN-13: 978-1-84739-664-8

ISBN-10: 1-84739-664-X

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either a product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual people living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

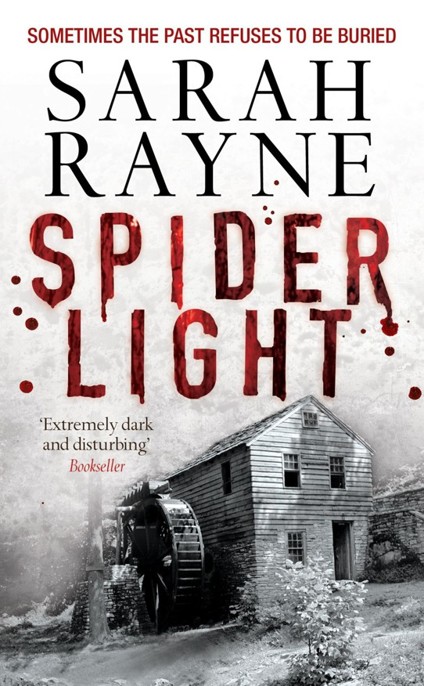

My grateful thanks are due to Craig Ferguson and his National Trust colleagues at Nether Alderley Mill in Cheshire, who were so very helpful when I was researching this book.

The time I spent at the beautifully maintained Mill was immensely valuable in the writing of

Spider Light

, and Craig and his team gave generously and enthusiastically of their time and knowledge.

The layout and atmosphere of Twygrist are unashamedly based on Nether Alderley Mill, but there the similarity ends. Nether Alderley has almost certainly never been the setting for the strange and often macabre events that take place within the walls of Twygrist.

Sarah Rayne

2005

After five years away from the world, the first thing to strike Antonia Weston about her return to it was the noise. She had forgotten how loudly and how energetically people talked, and how shops and eating-places were filled with intrusive music. It was, it seemed, dangerously easy to believe you had kept up-to-date, but when it came to it, you might as well have been living on the moon.

Even something as simple as entering the restaurant where she had arranged to meet Jonathan Saxon was a culture shock. Antonia managed not to flinch from what felt like a wall of sound, and to avoid staring at the people at other tables. But just as she had forgotten how loud the world was, she had also forgotten how fashions could change for ordinary people. Not startlingly, not drastically–not in the way of celebrities or TV stars–but more subtly. Had these sleek svelte girls, who were having their lunch and who probably worked in management consultancy or PR or in the still bewildering world of the internet, always dressed in dark, almost masculine suits, and worn their hair quite so casually?

One thing she had not forgotten, though, was Jonathan’s habit of opening a door with an impatient rush, so that people looked

up from whatever they were doing or saying to see who had come in. It was a trick Antonia remembered him using at meetings, deliberately arriving late and then switching on a beam of crude masculine energy at the exact right moment. It had always annoyed Antonia and it annoyed her now, especially since at least six people in the restaurant were responding exactly as if somebody had tugged an invisible string. (All right, so it was an

effective

trick. That did not make it any less irritating.)

‘I’m sorry about the tumult in here,’ said Jonathan, sitting down and studying Antonia intently. ‘I expect it’s a bit shrill for you. But I wasn’t expecting you until next week, and I couldn’t think of anywhere else that was easy to get to.’

‘Change of date at the last minute,’ said Antonia offhandedly. She studied the menu and, with sudden anger, said, ‘I don’t know what to order.’

‘Poached salmon?’

‘Oh God, fresh salmon. I’d forgotten there was such a thing in the world. Yes, please.’

‘And a glass of wine with it? Chablis?’

‘I–no, I’d better not.’

‘You used to like wine,’ said Jonathan, raising an eyebrow. ‘Or are you frightened of the consequences?’

‘I’m frightened of sliding under the table. You try not having a drink for the best part of five years and see how strong your head is.’

‘Fair enough,’ he said equably, and ordered mineral water for her and a carafe of wine for himself.

When the food came he ate with swift economy. This was something Antonia had forgotten about him. For all his tricks and deliberately created effects, his movements were always oddly pleasing. Feline. No, make that wolfish. This was the man who was rumoured to have systematically slept his way through medical school and to have continued the process when he became head of psychiatric medicine at the big teaching hospital where he and Antonia had first met.

‘I thought,’ he said, ‘that you’d want to get right away for a while. That’s why I wrote to you. And someone at the hospital mentioned a cottage that’s available for a few months–it’s somewhere in Cheshire.’

It would be one of his women who had mentioned it. Saxon’s string puppets, someone had once called them: he pulls the strings and they dance to his music.

‘It’s apparently a very quiet place,’ the man who pulled the strings was saying. ‘And the rent’s quite reasonable.’ He passed over a folded sheet of paper. ‘That’s the address and the letting agent’s phone number. It might give you a breathing space until you decide what to do next.’

‘I haven’t the least idea what I’m going to do next,’ said Antonia, and before he could weigh in with some kind of sympathy offer, she said, ‘I do know you can’t re-employ me. That the hospital can’t, I mean.’

‘Yes, I’m sorry about that. We all are. But it would be a great shame to waste all your training. You could consider teaching or writing.’

‘Both presumably being available to a struck-off doctor of psychiatric medicine.’ This did not just come out angrily, it came out savagely.

‘Writing’s one of the great levellers,’ said Jonathan, not missing a beat. ‘Nobody gives a tuppenny damn about the private life of a writer. But if you’re that sensitive, change your name.’ He refilled his glass, and Antonia forked up another mouthful of the beautifully fresh salmon which now tasted like sawdust.

‘I don’t suppose you’ve got much money to fling around, have you?’ he said suddenly.

Antonia had long since gone beyond the stage of being embarrassed about money. ‘Not much,’ she said. ‘What there is will probably last about six months, but after that I’ll have to find a way of earning my living.’

‘Then why don’t you rent this cottage while you look for it? Whatever you end up doing, you’ve got to live somewhere.’

‘It’s just–I’m not used to making decisions any longer.’ This sounded so disgustingly wimpish that Antonia said firmly, ‘You’re quite right. It is a good idea. Thank you. And can I change my mind about that wine?’

‘Yes, of course. If you slide under the table I promise to pick you up.’

‘As I recall,’ said Antonia drily, ‘you were always ready to pick up anyone who was available.’

Appearance did not really matter, but one might as well turn up at a new place looking halfway decent.

Antonia spent two more days in London having her hair restyled into something approximating a modern look and buying a few clothes. The cost of everything was daunting, but what was most daunting was the occasional impulse to retreat to the small Bayswater hotel where she was staying and hide in the darkest, safest corner. This was a reaction she had not envisaged or bargained for, even though it was easily explained as the result of having lived in an enclosed community for so long and a direct outcome of being what was usually called institutionalized. Still, it was ridiculous to keep experiencing this longing for her familiar room, and the predictable routine of meals, work sessions, recreation times.

‘I expect you like to simply wash your hair and blast-dry it, do you?’ said the friendly hairdresser while Antonia was silently fighting a compulsion to scuttle out of the salon and dive back to the hotel room. ‘So much easier, isn’t it, especially with a good conditioner?’

Antonia said yes, wasn’t it, and did not add that for five years she had been used to queuing for the communal showers each morning, and hoarding a bottle of shampoo as jealously as if it was the elixir of eternal life.

Clothes were more easily dealt with. She bought two pairs of jeans, a couple of sweaters, and some trainers, at a big chain-store in Oxford Street. Then a cup of coffee and a sandwich at

the crowded self-service restaurant–yes, you

can

cope with being out for another hour, Antonia! After this modest repast she hesitated over a trouser and jacket outfit the colour of autumn leaves. Useful for unexpected invitations, and an absolutely gorgeous colour. Oh sure, and when would you wear it? Or are you expecting the locals at this tiny Cheshire village to sweep you into a dizzy social whirl the minute you arrive? In any case, you can’t possibly afford clothes like that, said a bossy voice in her head, this is the boutique section, and look at the price tag for pity’s sake! This remark tipped the balance irrevocably. Antonia came out of the shop with the autumn-brown outfit lovingly folded into its own designer-label bag.

The cottage suggested by Jonathan’s contact or newest bed partner or whatever she was, apparently stood in the grounds of an eighteenth-century manor. It was called Quire House and it had been converted into a small museum–Charity Cottage was apparently a former tied cottage in its grounds. Antonia thought the name smacked of paternalism and gentrified ladies visiting the poor with baskets of calf’s-foot jelly, and thought she would probably hate it.

But by this time she was committed. She had sent a cheque for two months’ rent which she certainly could not afford to forfeit, and had received by return of post a standard short-term lease agreement. This granted her full and free enjoyment of the messuage and curtilage, whatever those might be, permitted various rights of way depicted in red on a smudgily photocopied plan which presumably allowed her to get in and out of the place, and wound up by forbidding the playing of loud music after eleven at night, the plying of any trade, profession or business whatsoever, and the entertaining of any rowdy, inebriated or otherwise disruptive guests.

Charity Cottage, Amberwood. It sounded like a cross between Trollope and the

Archers

. I won’t be able to stand it for longer than a week, thought Antonia, rescuing her car which had been standing in an ex-colleague’s garage for the past five years, and

which the ex-colleague had generously kept serviced for her. It’ll either be impossibly twee or tediously refined, and Quire House will be one of those earnest folksy places–afternoon classes in tapestry weaving, and displays of bits of Roman roads dug up by students. Or it’ll be a sixties-style commune, with people trading soup recipes or swapping lovers. If they find out I’m a doctor they’ll consult me about bunions or haemorrhoids, and if they find out I’m a psychiatrist they’ll describe their dreams.

But I certainly won’t get within hailing distance of any rowdy guests. Nor will I be plying a profession.

It felt odd to have a latchkey again; the agents had sent it by recorded delivery, and Antonia had had to phone them to confirm its arrival. This was somehow rather comforting; it was a reminder that there was still a world where people cared about privacy and where they took trouble to safeguard property. Perhaps it might be all right after all, thought Antonia. Perhaps I’ll find I’ve made a good decision.

There was more traffic on the roads than she remembered, and it was much faster and more aggressive, but she thought she was doing quite well. She did not much like launching out into the stream of cars on the big roundabouts, but she managed. So far so good, thought Antonia. All I’ve really got to worry about is finding the way.

Richard had always teased her about her appalling sense of direction; he had usually made some comment about the Bermuda triangle, or quoted the old Chesterton poem about the night we went to Birmingham by way of Beachy Head. But then he would reach for the map and study it with the intensity that was so much part of him, after which he would patiently and clearly point out the right route and send Antonia the sideways smile that made his eyes look like a faun’s. It had been five years since Antonia sat in a car with Richard, and it was something she would never do again.

She stopped mid-journey to top up with petrol and have a cup

of tea–it was annoying to find it took ten minutes to talk herself into leaving the safety of the car to enter the big motorway service station. I’ll master this wretched thing, said Antonia silently, I

will,

I’ll turn on the car radio for the rest of the journey or put on some music–yes, that’s a good idea.

Before starting off again she rummaged in the glove compartment for a tape. There was a bad moment when she realized that some of Richard’s favourite tapes were still here, but she pushed them determinedly to the back and sorted through the others to find something sane and soothing. There was some old pop stuff, which would be lively but might remind her too much of the past. Was it Noël Coward who said, ‘Strange how potent cheap music is?’ Ah, here was Beethoven’s

Pastoral Symphony

. Exactly right. Hay-making and merry peasants and whatnot.

Beethoven had just reached the ‘Shepherd Song’ and Antonia thought she was about forty miles short of her destination, when a vague suspicion began to tap against her mind and send a faint trickle of fear down her spine.

She was being followed.

At first she dismissed the idea; there were enough cars on the road to mistake one for another, and there were dozens of dark blue hatchbacks of that particular make.

She watched the car carefully in the driving mirror, and saw that it stayed with her, not overtaking or quite catching up, but persistently there. I’m seeing demons, thought Antonia. There’s nothing in the least sinister about this, just two people going in the same direction.

Without realizing she had planned it, she swung off the motorway at the next exit, indicating at the last possible moment, and then took several turnings at random. They took her deep into the heart of completely unknown countryside and into a bewilderment of lanes, out of which she would probably never find her way, so it really would be Beachy Head by way of Birmingham. But getting lost would be worth it if it proved to her stupid neurotic imagination that no one was following her.

It would prove it, of course. The man who had once driven a dark blue car–the man who had ruined her life–could not possibly be tailing her along these quiet roads. He was dead, and had been dead for more than five years. There could not possibly be any mistake about it. And she did not believe in ghosts–at least, she did not believe in ghosts who took to the road in blue hatchbacks, and whizzed along England’s motorways in pursuit of their prey.

She glanced in the driving mirror again, fully prepared to see a clear stretch of road behind her, and panic gripped her. The car was still there–still keeping well back, but definitely there. Was it the same car? Yes, she thought it was. She briefly considered pulling onto the grass verge and seeing what happened. Would the driver go straight past? (Giving some kind of sinister, you-are-marked-for-death signal as he went…? Oh, don’t be ridiculous!)

Still, if he did drive past she could try to see his face. Yes, but what if there wasn’t a face at all? What if there was only something out of a late-night, slash-and-gore film? A grinning skull, a corpse-face?

It had not been a corpse-face that first night in the tiny recovery room off A&E. It had been an attractive, although rather weak face, young and desperately unhappy. Antonia could still remember how the unhappiness had filled the small room, and how the young man in the bed had shrugged away from the doctors in the classic but always heart-breaking gesture of repudiation. Face turned to the wall in the silent signal that said, I don’t want to be part of this painful world any longer. At first he had turned away from Antonia, who had been the on-call psychiatrist that night. She had been dozing in the duty room on the first floor when her pager went, and she had paused long enough to dash cold water onto her face, slip into her shoes and pull on a sweater before going quickly through the corridors of the hospital.