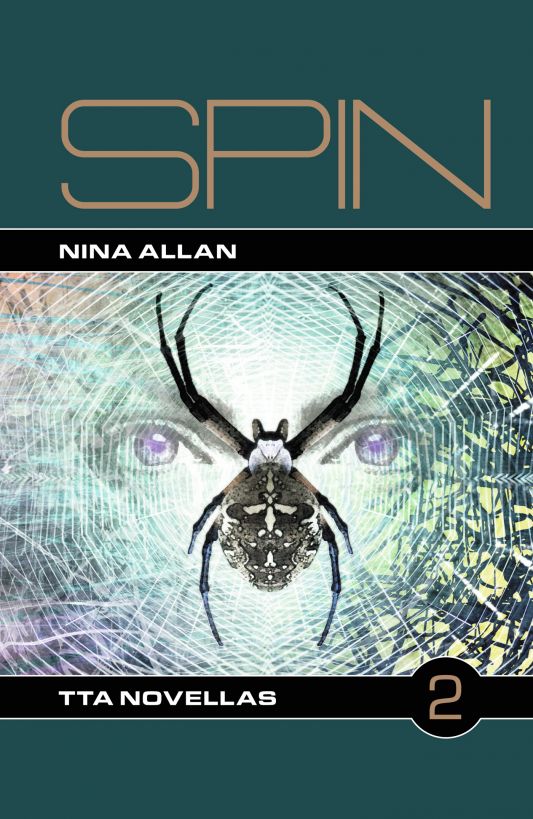

Spin

Authors: Nina Allan

Tags: #fantasy, #science fiction, #prophecy, #mythology, #greek mythology, #greece, #weaving, #nina allan, #arachne myth

BY NINA ALLAN

* * * * *

.

First published 2013 by

TTA Press

Print Edition ISBN

978-0-9553683-6-3

Smashwords Edition

ISBN: 9781301417698

Copyright © Nina Allan

2013

Cover by Ben

Baldwin

Copyright © Ben Baldwin

2013

The right of the author

to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in

accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No

part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the

prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise

circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which

it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on

the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record

for the printed version of this book is available from the British

Library

Proofread by Peter

Tennant

Designed and typeset

for print by the publisher,

Ebook v2 RG

TTA Press

5 Martins Lane

Witcham

Ely, Cambs

UK, CB6 2LB

ttapress.com

* * * * *

Smashwords Edition

License Notes

This ebook is licensed

for your personal use/enjoyment only. It may not be re-sold or

given away to other people. If you would like to share this ebook

with others please purchase an additional copy for each recipient.

If you are reading this ebook and did not purchase it, or it was

not purchased for your use only, then please go to Smashwords.com

and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work

of the author and publisher.

* * * * *

For my father,

Stuart Stephen Allan

* * * * *

* * * * *

Low was her

birth, and small her native town,

She from her

art alone obtain’d renown.

Idmon, her

father, made it his employ,

To give the

spungy fleece a purple dye:

Of vulgar

strain her mother, lately dead,

With her own

rank had been content to wed;

Yet she their

daughter, tho’ her time was spent

In a small

hamlet, and of mean descent,

Thro’ the

great towns of Lydia gain’d a name,

And fill’d the

neighb’ring countries with her fame.

from

Metamorphoses, Book the Sixth, The Transformation of

Arachne into a Spider

by Ovid, translated by John Dryden

Her father was not there to say goodbye. It

was not

unusual

for him to get up early and take the boat out, but

Layla knew that today it was deliberate, that he didn’t want to see

her leave. She walked to the bus stop by way of the harbour front,

hoping she might still catch a glimpse of him, his body a taut line

above the water as he pulled back on the

Auster

’s sail rope, aiming the sea kite into the sunrise

like an arrow into fire. She scanned the horizon expectantly,

shading her eyes with both hands, but there was no sign of him. He

was too far out by now, probably. It might be several hours before

he returned.

She arrived at

the harbour bus stop just after six. Dawn was stepping from the sea

on to the sand. When she was a child Layla liked to imagine that

her mother would come back to her that way, rising smoothly out of

the water she had been drowned in, her sodden dress clinging to the

curves of her body like a second skin, her long feet high-arched

and pearly white in their pink suede flip-flops.

The stop was

deserted. The seven o’clock shuttle would be much busier, something

Layla had wanted to avoid. As it was the bus came late, rattling

along the coast road in a trail of diesel fumes and fine white

dust. She showed the driver her ticket then sat down on a bench

near the front. She disliked the back seats, where the cloth

merchants and wool gatherers played out their endlessly rolling

whist tournaments and gave one another black eyes when they started

to lose. She stowed her rucksack under the seat. This made the

space more cramped but she didn’t feel like trusting her luggage to

the open rack.

As the bus

drew away from the waterfront and headed inland Layla wondered if

it was true, what her nurse Iona had told her, that once you were

away from the coast the Mani became another country entirely. She

could sense the land’s rough breathing, so different from the

sweet-mouthed breezes that stirred the breakers along the shoreline

at Kardamyli. The road across the mountains was bumpy and

gravel-strewn, still unmade in places, the slopes above steeped

thickly in stunted olives and golden saxifrage. For the first time

since buying her ticket, Layla felt queasy with doubt and something

she supposed was homesickness. If the Taygetus were another

country, Atoll City itself was an alien world.

They came into

Kalamata at around midday. This was a scheduled rest stop, an hour

to stock up on food or just stretch your legs. Layla walked down to

the harbour, where a consignment of mirror glass was being unloaded

from a steam freighter and lifted in gleaming stacks on to the open

bed of a sky truck. The navvies glistened with sweat, while a tiny

bearded man clutching an iPad dashed around yelling instructions.

Layla bought a crab sandwich and watched the harbour traffic as it

inched slowly towards the exit slipway that led to the ring road.

The people in the cars were brightly dressed, their cheap garments

a rainbow of synthetics, reductions of the hues her father had

taken decades to perfect. Their loud cacophony raised an itching

sensation in her nerve endings.

At five

minutes to the hour she began to walk back. She knew more

passengers would be boarding at Kalamata, and she didn’t want to

risk losing her seat. By the time the rest stop was over the bus

was full. The seat beside her, empty until the rest stop, was now

occupied by an old woman. She was stick-thin, and frightening to

look at, ugly in a way that was almost freakish. On her lap she

held a knapsack, a leather drawstring bag that seemed to heave and

pulse with a life of its own. Layla dreaded to think what horror

might be inside. She stared fixedly out of the window, determined

not to meet the crone’s gaze. She yearned to get out her

embroidery, but her rucksack had slipped right back under the seat

and she didn’t want to draw attention to herself by rummaging for

it. It would be another five hours until they stopped for the night

in Corinth. The thought of having the old woman wedged up against

her for the duration made her feel sick. There was a toilet break

at Tegea, where to Layla’s surprise the old woman vacated her seat

as soon as the vehicle came to a standstill. Layla snatched up her

rucksack and got off the bus. There was a roadside drinking

fountain, a rusted length of piping set straight into the rock.

Layla drank, filling her mouth and throat with the taste of coins.

In spite of the heat of the day the water was icy.

The cicadas

were in uproar. The uneven road shimmered in the heat like a

mirage. After ten minutes or so the bus driver blew a whistle and

everyone began to re-embark. Layla pushed to the front, not wanting

the old crone to get ahead of her and grab the window seat. When

the old woman didn’t appear she felt surprised. As they lurched out

of the lay-by Layla scanned the roadside, half expecting to see her

hobbling after the bus at a stunted run, the bulging leather sack

clutched to her chest. There was no sign of her, however, and the

seat beside Layla remained empty.

As the evening

drew on the light softened, winding down from topaz through

sapphire to a dusty amethyst. Layla opened her rucksack and drew

out the miniature panorama she had been working on before she left.

It was scarcely begun, with just one bright corner of stitching as

proof of what she intended, but already the piece possessed her,

had become for her as each new work inevitably did a material

extension of her spirit.

She was using

the smallest of her embroidery frames, the only one she had that

would fit inside her rucksack without having to be taken apart. It

was made of gingko wood, the timber sanded and then sealed with

teak oil, its two interlocking sections a perfect fit. It had been

Iona who had first shown her how to use it, how to stretch the

canvas as tight as it would go over the inner circle then secure it

by winding the four brass screws on the outer ring. Layla had been

four at the time, and making a nuisance of herself by excavating

the contents of Iona’s work basket.

No doubt Iona

believed the child in her charge would soon become bored when faced

with having to do something more constructive than simply making a

mess; as it turned out she was wrong. By the afternoon of the same

day, Layla was able to form a simple cross-stitch. A week later she

presented her father Idmon with her first tapestry. The work was

simple but it was extraordinary nonetheless. Where a less

complicated child might have tried to work a simplified diagram of

the house she lived in, say, or her pet monkey, the four-year-old

Layla Vargas had coloured the entire area of the circular canvas

with a forest of green stitching, an abstract design created from

the odd tag ends of test silk she had found scattered beneath the

workbenches of the master dyers. Idmon Vargas counted twenty-six

different shades of green in all. The stitching itself was almost

perfectly uniform, the standard of workmanship you might expect

from a girl three times Layla’s age or even more.

Layla

remembered being made a fuss of, she remembered becoming aware that

in the eyes of Iona and her father and the workmen in the silk

shops she had performed an unusual feat. But in her own mind these

things were marginal and surface, like the wavelets that scurry

along the shoreline at the first breath of wind. What mattered to

her was the thing that happened inside her when she thought about

silk. Until the day she learned to cross-stitch she had been

surrounded by colour and texture without realising that something

might be made of it. Afterwards the gingko frame became for her an

‘o’ as vast as the world, a circular window she could climb through

into realms and realities of her own choosing. With this ‘o’ she

could draw sense from colour and make it her slave. She could bind

it to herself, refine it as the High Priestess at Delphi refined

the empty echoes in the hollow rocks below and brought them forth

into daylight as the voice of a god.

When she was

twelve years old, Layla suddenly became convinced that her mother,

Romilly Perec, had been a sibyl. It was the only way she could

think of to explain her gift, and although all savants now held

equal rights under the law, she had learned at school that sibyls

were still being executed for crimes of clairvoyancy as little as

ten years ago, especially in the provinces.