Spirited (18 page)

Authors: Judith Graves,Heather Kenealy,et al.,Kitty Keswick,Candace Havens,Shannon Delany,Linda Joy Singleton,Jill Williamson,Maria V. Snyder

The oast house, like any old building, had been standing long enough to harbor many secrets. Whatever mysteries were buried deep within these walls had been suppressed for too long, denied for too long. But while I lived here, the oast fed on my energy, taking it all, draining me until I had nothing left to give. The heart of the oast was beating out its broken rhythm one drop at a time.

I staggered forward as the oast pulled me toward the truth. I passed the light switch on the landing but left it untouched.

I passed my father’s empty room.

I passed the window that overlooked the fields and the brewery.

Plink.

The oast house was steeped in darkness. I wasn’t afraid of the unseen horrors of my childhood tonight—no hands would grab me, no shivering breath would tickle the back of my neck. Whatever was here was real. And it waited for me now.

A shaft of moonlight from the window marked the bathroom doorway. Although it was only a small offering of light, it would have to suffice.

I crept closer until I stood at the doorway. I entered the room with my eyes squeezed shut, pressing my toes against the cold tiles one small step at a time

The dripping stopped the moment I walked through the door. I envisioned my mother the last time I had seen her. She’d lain in the tub with her back toward me, her hair spilling out over the rim of the bath. The water ran red with her blood as she lay across the thin line between life and death.

I opened my eyes and wiped away tears as I tried to make sense of the scene before me.

The floor wasn’t tiled as it had been the last time I’d entered the bathroom. Instead, the floor was untreated oak. The walls were stone, and in the air hung the thick, bitter smell of dried hops.

Everything as it had been had disappeared. Nothing remained except for the body on the floor.

“Isobel,” I breathed.

I knelt beside her battered body and smoothed the hair from her face.

I checked her cold skin for a pulse, but felt none. The little girl lay dead, surrounded by broken beer bottles in the aftermath of a drunken and violent frenzy.

A muffled creak like a door opening downstairs, startled me, and I left Isobel to check it out. I fought panic as I peeked over the railing to the entrance hall below.

“Ty?” my father called up.

I stared back blankly.

“What are you doing up so late?” he said.

“I… what are you doing here?” I glanced from him to the bathroom.

My father sighed. “I forgot my ID.”

I could think of nothing to say to him in that moment. My thoughts were with Isobel alone, and I stepped back through the door to the scene of her demise.

The room had returned to normal. I flicked on the light and faced nothing more than the dirty tiles and the frosted mirror.

“Isobel?”

The tears on my face had dried. Was I losing my sanity? First my mother, then the girl from the brewery. It had all seemed so real.

My father’s boots clomped on the tile as he approached. I was slumped on the floor next to the bathtub. I didn’t even realize I was crying again until Dad crouched next to me and placed a hand on my shoulder.

“It’s going to be okay,” he said. He took me by the arm and led me away from the bathroom, away from my memories. I lay down on top of my bedcovers and closed my eyes. The oast house was silent, but it rang with the echo of my father’s voice:

It’s going to be okay

.

When I woke the next morning, I had more pressing matters to deal with than algebra. As soon as I’d dressed, I ran straight across the fields to the brewery. I didn’t stop to catch my breath as I headed for the stairwell and the upstairs room where I’d found Isobel hiding before.

“It’s me. Open the door,” I called.

The door opened, and Isobel stood before me as she had done previously. She smiled, but I couldn’t return the gesture.

“What happened last night?” I asked.

Isobel’s brow creased. “What do you mean?”

“You were in my house.” I folded my arms across my chest.

She shook her head. “No, I wasn’t.”

I sighed and ran a hand through my hair. “I don’t want to play games, Isobel. I don’t know who you are—or what you are—but I saw you.” The word

dead

was on the tip of my tongue, but I couldn’t bring myself to say it. “Come outside with me.” I reached for her arm, but she sprang back.

“No,” she cried.

I stepped closer to her and held out my hand. I took another step. Isobel retreated farther into the corner of the vast room. I strode forward. I needed answers. Isobel stopped only when her back hit the wall.

“Come with me,” I said.

Tears streamed down her face. I forced myself to remain unmoved. “You either

can’t

, or you

won’t

.”

“I tried to tell you,” she whispered. Her tears continued to flow. “Ever since the other people… I’ve been stuck here. Please help me.

Please

.”

Leaving Isobel, I ran back through the fields to the oast house. Her secret lay within those walls, and I intended to discover it even if it killed me.

I grabbed a crowbar from the mudroom and took the stairs two at a time.

Plink.

My footfalls on the treads of the stairs matched the pounding rhythm of the dripping in the bathroom.

Plink. Plink

.

I hoped my father would understand what I planned to do. I’d need an explanation that wouldn’t get me grounded for life.

Plink.

The dripping grew louder and louder, reverberating in my eardrums as I entered the bathroom. I cried out in pain. Dropping the crowbar, I pressed my palms over my ears to block out the noise.

Clenching my fists until my fingernails pierced my skin, I braced myself. I snatched up the crowbar. I struck at the tiles. Some of them resisted and merely cracked. Others fell and shattered on the floor. I smashed at the wall until I broke through the plaster and reached the ancient laths underneath. The thudding in my ears was almost unbearable.

Part of the bathroom had been insulated. I tore out sections of foamy insulation to find nothing. I moved on to other sections of the wall. Nothing. I slid to the floor, exhausted. “What am I supposed to do?” I raked my hands through my hair.

When the morning sun, light as the sunburned fields, shone in through the window, one golden ray landed in the center of the mirror. Swiping plaster dust from my eyes, I jumped up.

With the crowbar, I wrenched the mirror from the wall. The glass shattered as it hit the floor. I smashed through the plaster and then tore pieces away with my hands. The sink blocked my way, so I moved to the side of the vanity and yanked away chunks of plaster with newfound energy, barely noticing the gap made by the missing oak laths here. My heart was pounding. When the hole was large enough, I put my foot through and stepped inside the wall of the oast house.

The thudding drips ceased, plunging the room into a silence that enveloped my whole body. I blinked more dust from my eyes as they adjusted to the dark.

I plunged forward in the small space. The hollow was less than six feet deep, but without light the space seemed as immense as a bottomless pit. The stonework of the walls was the same as I’d imagined it, and I could make out an indistinct mass lying on the floor.

With shaking hands, I leaned down to pull away the crumpled sheets covering it, but stopped. Lying on the ground was a shoe. Small and dusty. A child’s shoe. I didn’t touch the sheets. I didn’t want to see Isobel that way.

~*~*~

I visited my mother after the inquest. I told her about school and the drama club. I told her about the color of field grass when the frost burns it white. But I didn’t tell her about the brewery or the oast house. My mother needed to hear stories about life and living, and Isobel’s story was not yet finished. Her death remained unsolved. It would only be complete when she chose to tell me about it.

Since the day in the bathroom, Isobel hasn’t reappeared.

Even cold and empty, the brewery hints at stories it wants to tell, and although Isobel no longer hides behind its crumbling walls, she has to be somewhere nearby. After all, she needs my company. And I need hers.

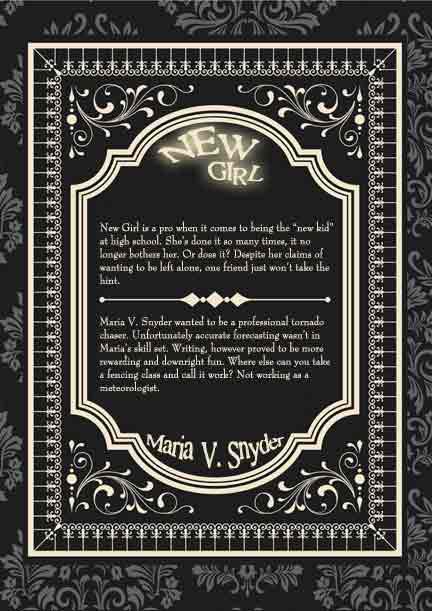

New Girl

New Girl

I’m the new girl. Always am. Don’t worry, it doesn’t bother me anymore. I’m a pro. It’s so easy to ignore the stares of the other students as I stand on the steps leading into the main entrance of another Dead President High School. I’m in some town in Wisconsin. Or is it Minnesota?

All I know is, it’s cold and bleak here, my mother’s still dead, and there’s nothing to distinguish this place from any other town in the Midwest. Just like the school. It resembles the one I attended before and the dozen I attended before that. I can predict my first day here without fail.

One of the type-A cheerleaders will show me around. She’ll be friendly, bubbly, and introduce me to all my teachers. And then she’ll abandon me ‘cause I’m not one of her “people.” She will have determined my place in the high school hierarchy thirty seconds after meeting me by assessing my average—i.e., not designer—clothes, my generic backpack, and well-loved purple sneakers. She’ll rate me slightly better than the freaks, geeks, and invisible types, but far below her own exalted station.

I’ll try not to laugh at her, ‘cause I’ve seen her type in every high school across the United States. There’s nothing special about her or anyone in this place. Millions just like them are forming the same cliques, dealing with the same problems, and all believing they’re special.

In fact, nothing will surprise me today. The jocks, the goths, and the teachers will meet my low expectations. The faces and names might be different, but that’s it. I’ll attend my classes amid whispered speculation, rude stares, and I’ll see that hopeful gleam in a few girls’ gazes. You know the type—the fringers who don’t have any friends. They’ll see the new girl as a potential new BFF.

I’ll ignore them. It’s kinder this way, trust me. If we become BFFs, I’ll only break their hearts when I leave to attend the next Dead President School or Dead Humanitarian School. ‘Cause I will leave. That’s a guarantee.

Maybe not for a month or two, but my dad will find another job that will be too good to pass up, and off we’ll go.

So I know you’re wondering why I still bother with school. I’m sixteen and could just quit. But, you see, attending college is my goal. Why? ‘Cause college means I get to stay put for four whole years. When I’m in college, I won’t be dragged from place to place, and I can make a friend without worry.

And as I predicted, my day plays out like it has too many times to count. At the end of the first day, I retreat to the library. Sorry, I guess I should say the Learning Resource Center, or the Media Center, or the IMC. Doesn’t matter what it’s called, it’s my place to study and hang out until my dad picks me up.

I’d rather be here than in some hotel room. Wouldn’t you? I find a spot that’s hidden and quiet and make it my temporary home.

Except this time, my spot isn’t quite as hidden as I’d thought.

“Hey, you’re the new girl, aren’t you?”

I stare at the “genius,” deciding between a sarcastic reply or cold silence to drive him away. He looks like a fringer, but he could be one of the invissies. I opt for silence, but he doesn’t get the hint.

“I’m Josh Martin.” He plops in the chair on the opposite side of the table. He points to my open textbook. “I have Algebra Two with Mr. Kindt.”

When I don’t respond, he leans forward and says, “So what do you think about our school?”

I consider my options. What will drive him away the fastest? “Did you know there are forty-seven other high schools with the same name across the US?”

“Really? Wow. How do you know that?”

I suppress a groan and shrug. “Internet.”

“Cool.” He smiles at me.

Josh has freckles, a few pimples, and grayish green eyes. His shaggy brown hair curls at the ends. He’s wearing generic jeans, sneakers, a gray hoodie, and an L.L. Bean® backpack. At least he doesn’t have his initials stitched on it—that’s so lame.

Before I can tell him to get lost, he asks my most hated question, “So where are you from?”

I refuse to answer. Always will. Instead, I say, “Look, John—”

“Josh.”

“I have lots of work to catch up on.”

But he’s sixteen and male. Which means he’s denser than a dwarf star and unable to pick up on subtle hints. I try a more direct brush off. “Jack—”

“Josh.”

“Go away. Shoo!” I wave my hand.

But the idiot just gives me a goofy grin. He pulls out his Algebra Two textbook, flips the pages, and works on the assigned problems.

Whatever. I ignore him and concentrate on my own work. But he can’t keep quiet.

“Number five is tricky,” he says.

“What did you get for number nine?”

“Avoid the taco salad. It’s poison. But make sure you try the school’s french fries,” he says.

I don’t answer, but that doesn’t seem to matter to him. He gossips about the other students despite the fact I have zero interest.