Stalin's Daughter (14 page)

Authors: Rosemary Sullivan

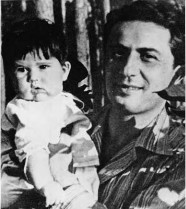

Yakov with his daughter, Gulia, 1939.

By early September, Sochi was no longer a safe refuge, and the family returned to Moscow. The ravages of the war were already apparent. From the windows of the Kremlin apartment, Svetlana could see a gaping hole on the corner of the Arsenal Building opposite, where a German bomb had hit. Vasili had been in the apartment and had been thrown from the bed as

the windows shattered.

23

She was terrified to discover that a bomb had fallen on Model School No. 25. Of course, it had already been evacuated. Construction crews were hastily building a bomb shelter inside the subway for the War Cabinet.

After their arrival, Stalin explained to Svetlana that there would be new arrangements: “Yasha’s daughter can stay with you for a while. But it seems that his wife is dishonest. We’ll have to look into it.”

24

Svetlana was appalled and had no idea what her father was talking about. How could Yulia be dishonest?

Yulia was arrested and incarcerated in the Lubyanka prison. Was it possible that another family member could disappear like this? When the last wave of family arrests had occurred in 1938, Svetlana had been twelve. Now she was fifteen, but she still did not understand. Who was doing this to her family?

On August 16, Stalin had issued Order 270, condemning all who surrendered or were captured as “traitors to the Motherland.” Wives of captured officers were to be arrested and imprisoned.

25

Yakov was a traitor; Yulia must be arrested. There would be no exception made for Stalin’s son.

Meanwhile poor Yulia was held in solitary confinement in the dark bowels of the dreaded Lubyanka. The “investigation” would take a year and a half. As the Germans advanced, she was transferred to a prison in Engels, on the Volga.

26

When she was eventually freed, in the spring of 1943, her five-year-old daughter, Gulia, did not recognize her and had to be encouraged to approach her mother. No explanation was ever offered to Yulia for her imprisonment. She was simply told she was free to go. She never spoke to Stalin again.

The news of what had actually happened to Yakov filtered out slowly. One report came from Ivan Sapegin, commanding officer of the 303rd Light Artillery Regiment. When Yakov’s armored division was encircled and overrun at Vitebsk in Belarus

on July 12, 1941, the divisional commander had fled the battlefield, but Yakov was separated from his unit and had been taken prisoner.

27

Yakov served as a Red Army artillery officer in World War II, and he was captured by the Germans on July 16, 1941.

The German command immediately informed Stalin by flash cable of his son’s capture and then used it for propaganda purposes. Pamphlets with a photograph of Yakov in his uniform without belt or epaulets, surrounded by German officers, were dropped on Soviet troops.

Stalin’s son, Yakov Dzhugashvili, full lieutenant, battery commander, has surrendered. That such an important Soviet officer has surrendered proves beyond doubt that all resistance to the German army is completely pointless. So stop fighting and come over to us.

28

Yakov languished in various POW camps until the spring of 1943, when, after their disastrous defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad, the Germans attempted to exchange him for Field Marshal

Friedrich Paulus. Stalin refused the prisoner exchange. That spring Yakov either was shot or committed suicide; it would never be known which. It would be several years before Svetlana knew her brother’s fate. In this she was like millions of her fellow Soviets.

With the Germans on Moscow’s doorstep and an invasion of the city imminent, the town of Kuibyshev to the southeast was chosen to be the alternative capital. In early October 1941, government personnel, foreign diplomatic missions, and cultural institutions began a hasty evacuation. Lenin’s mummified body had already been removed from its mausoleum and sent by secret train to Tyumen in Siberia.

As Moscow filled with smoke from the bonfires of burning archives, the Stalin family’s belongings were packed into a van. Most of the family was already in Kuibyshev, but it wasn’t yet clear whether Stalin would evacuate too, though it was assumed he would. The Kuntsevo dacha was booby-trapped, and a secret train to transport Stalin stood waiting at a railway siding.

In Kuibyshev, a small local museum on Pioneer Street was emptied of its exhibits and newly painted to house the Stalin family, along with bodyguards, cooks, and waiters. Svetlana’s nanny came with her, as did Mikhail Klimov, her personal “secret police watch-dog,” as she called him. Vasili’s young wife, Galina (they had married in 1940, when Vasili was nineteen), was there. While Grandmother Olga came, Grandfather Sergei had decided he would return to Tbilisi and spent most of the war in Georgia. At Svetlana’s urging, Yakov’s baby daughter, Gulia, was soon permitted to join them.

Stalin elected to stay in Moscow to conduct the war. Svetlana wrote to her father from Kuibyshev on September 19, 1941.

My dear Papochka my dear happiness. Hello.

How do you live my dear Secretary? I am fine here. In our

school there are other kids from Moscow. There are many of us so I am not bored.

I only miss you … now especially I want to see you. If you allow me, I could fly on a plane there for two or three days….

Recently a daughter of Malenkov and the son of Bulganin … left for Moscow, so if they can fly why can’t I? They are the same age as me and in general they are in no way better than I am….

I don’t like the city very much…. There are many, and I don’t know why, people who are blind…. Every 5th person is a disabled man. Very many poor people and urchins. In Kuibyshev during the war, many people came from Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev, Odessa and other cities and the locals treat the incomers with an anger they don’t hide….

And now Hitler will come and will bomb this place…. Papa, why do the Germans keep coming and coming? When will they finally get a kick in the neck? After all we cannot give up all our industrial areas.

Papa, I have one more request for you. Yasha’s [Yakov’s] daughter Galechka [Gulia] is right now in Sochi…. I would very much like for Galechka to be brought to me here. Now she has no one….

Dear Papa … I wait for your permission to take a flight to Moscow. But only for two days … I don’t know when you are free and that’s why I don’t call…. I kiss you many many times once again.

Svetanka

29

The fifteen-year-old Svetlana was by turns petulant, begging, naive, and then, finally, generous. She was a daughter fearful for her father so far away and in danger, a daughter with expectations: she must be flown to see him. On October

28, Stalin gave her permission to travel to Moscow. It was the day the Bolshoi Theater, the university buildings on Mokhovaya Street, and the Central Committee building on Staraya Ploshchad (Old Square) were bombed. She found her father in his bomb shelter, reached by an elevator descending ninety feet into the ground. The commissars had exactly replicated his rooms at Kuntsevo, lining the walls with wood paneling, though now they were covered in maps. The same dining room table had been installed for his dinner guests, who were the same men, but now uniformed officers. The table was also covered with maps, and telephone lines snaked through the rooms. Stalin was constantly in contact with the front. Svetlana was, of course, in the way.

As millions starved in the cities under siege, life in Kuibyshev often had a strange, surreal normalcy. Musicians who had been evacuated from Moscow formed a philharmonic orchestra, and there were concerts. Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony was premiered in Kuibyshev and broadcast around the world. The war was a shadow presence. Health centers and most of the city’s hospital facilities were turned into base hospitals as the wounded arrived with devastating injuries.

A makeshift cinema had been constructed in the ex-museum next to the kitchen, and there everyone watched the newsreels from the front. The cameramen were in the trenches and accompanied the advancing tanks. Svetlana watched battles on the outskirts of Moscow. She soon lost her naïveté about the meaning of war.

That spring in Kuibyshev, Svetlana made a devastating discovery that she claimed shattered her life. Her father had instructed her to keep up with her English language skills now that Britain and the United States were Russia’s allies, and so she had taken to reading any English or American magazine she could lay her hands on. She read

Life, Fortune, Time

, and

the

Illustrated London News.

One day that spring (she had just turned sixteen), she came across an article about her father. It mentioned, “not as news but as a fact well known to everyone,” that his wife, Nadezhda Sergeyevna Alliluyeva, had killed herself on the night of November 8, 1932.”

30

The shock of this revelation was heart-stopping. Svetlana rushed to her grandmother, article in hand, and demanded to know if her mother had committed suicide and why this had been hidden from her. Olga replied that, yes, it was true. Nadya had had a small gun. It had been a gift from Pavel. Olga kept repeating, “Who would have thought it?”

Marfa Peshkova remembered Svetlana showing her the magazine with the article. “I remember this very well. She showed me this photograph. It was a photograph of her mother lying in the coffin. She had never seen this. And somewhere … she did not know for sure about the death of her mother. It was rumored then that she died from appendicitis, from a failed operation or something like that. For her it was a shock.”

31

When Svetlana had read the article, she hadn’t wanted to believe it, but her grandmother had confirmed it. Her mother had killed herself. Only she, her daughter, seemed not to know. Her anger at her mother’s betrayal of her must have been profound. And she turned that anger on her father. She knew how he could be. She had seen him become mean, even brutal. She was certain it was his cruelty that had caused her mother to commit suicide. Now she began to switch her allegiance to the memory of her mother, but like all orphans of suicides, she would need decades to forgive Nadya for abandoning her.

Things that had been mysterious before suddenly became clear. When her father had said to her over the phone, “Don’t say anything to Yulia for the time being,” it hadn’t been solicitude he was expressing. It was suspicion. The idea of Yulia and Yakov betraying their country was inconceivable. Svetlana

began the slow process of realizing that her father was capable of condemning innocent people to prison and even to death.

She would look back and say, “The whole thing nearly drove me out of my mind. Something in me was destroyed. I was no longer able to obey the word and will of my father and defer to his opinions without question.”

32

This is the voice of an adult, but certainly Svetlana’s adolescent confusion must have been overwhelming. Which was more devastating: her belief that her father was responsible for her mother’s death or her discovery that her mother had not loved her enough not to kill herself?

Everywhere—at home, at school—her father was called the wise, truthful leader. Stalin’s name was linked to winning the war. He was the great Stalin. Only he could save Russia. To doubt him was an act of

blasphemy.

But Svetlana had begun to doubt.