Start Your Own Business (30 page)

Read Start Your Own Business Online

Authors: Inc The Staff of Entrepreneur Media

Too frequently, business owners fail to take the time to figure out exactly what kind of paperwork should be completed when they bor row from family or friends. “Often small-business owners put more thought into figuring out what type of car to buy than how to structure this type of lending arrangement,” says Steven I. Levey of accounting firm GHP Financial Group. Unfortunately, once you’ve made an error in this area, it’s difficult to correct it.

e-FYISimplify your money hunt at the Idea Café (businessownersideacafe. com). Click on “Business Financing” to find online calculators and self-evaluation worksheets that individualize the financing process so you can get the money that’s right for you and your business.

Your loan agreement needs to specify whether the loan is secured (that is, the lender holds title to part of your property) or unsecured, what the payments will be, when they’re due and what the interest is. If the money is in the form of an investment, you have to establish whether the business is a partnership or corporation, and what role, if any, the investor will play. To be sure you and your family and friends have a clear idea of what financial obligations are being created, you have a mutual responsibility to make sure everyone is informed about the process and decide together how best to proceed.

Most important, says McKeever, “Outline the legal responsibilities of both parties and when and how the money should be paid back.” If your loan agreement is complex, it’s a good idea to consult your accountant about the best ways to structure the loan (see the “Taxing Matters” section next).

Whichever route you take, make sure the agreement is in writing if you expect it to be binding. “Any time you take money into a business, the law is very explicit: You must have all agreements written down and documented,” says McKeever. If you don’t, emotional and legal difficulties could result that end up in court. And if the loan isn’t documented, you may find yourself with no legal recourse.

Taxing MattersPutting the agreement on paper also protects both you and your lender come tax time. Relying on informal and verbal agreements results in tax quagmires. “In these cases, you have a burden of proof to show the IRS that [the money] was not a gift,” says Tom Ochsenschlager, vice president of taxation for the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. If the IRS views it as a gift because there was no intention to repay it, then the lender becomes subject to the federal gift tax rules and will have to pay taxes on the money if it is more than $13,000. Also make sure the person providing the money charges an interest rate that reflects a fair market value.

If your friend or family member wants to give you a no-interest loan, make sure the loan is not more than $100,000. If you borrow more, the IRS will slap on what it considers to be market-rate interest, better known as “imputed interest,” on the lender. That means that while your friend or relative may not be receiving any interest on the money you borrowed, the IRS will tax them as if they were.

No interest is imputed if the aggregate loans are less than $10,000. Between $10,000 and $100,000, the imputed amount is limited to your net investment income, such as interest, dividends and, in some cases, capital gains. To determine the interest rate on these transactions, the IRS uses what it calls the applicable federal rate, which changes monthly. Keep in mind that if you don’t put all the details of the loan in writing, it will be very difficult for you to deduct the interest you pay on it. Additionally, the relative who lent the money won’t be able to take a tax deduction on the loss if you find you can’t repay.

“Right now, today,

with a little luck and

brains and timing, any

kid with a computer

can do what Netscape

has done. There are no

barriers to entry anymore.

Any kid can

spark a revolution.”—MARC ANDREESSEN, CO-

FOUNDER OF NETSCAPE

COMMUNICATIONS

To be absolutely safe, Ochsenschlager recommends that you make the friend or relative who is providing the money one of the business’ shareholders. This effectively makes the transaction an investment in your company and also makes it easier from a tax standpoint for your friend or relative to write off the transaction as an ordinary loss if the business fails. (This applies only if the total amount your company received for its stock, including the relative’s investment, does not exceed $1 million.)

In addition, “if your company is wildly successful, your relative will have an equity interest in the business, and his or her original investment will be worth quite a bit more,” Ochsenschlager says. In contrast, if a relative gives you a loan and your company goes under, the relative’s loss would generally be considered a personal bad debt. This creates more of a tax disadvantage because personal bad debts can be claimed as capital losses only to offset capital gains. If the capital loss exceeds the capital gains, only $3,000 of the loss can be used against ordinary income in any given year. Thus, an individual making a large loan that isn’t repaid may have to wait several years to realize the tax benefits from the loss.

SAVEYou don’t necessarily need a lawyer to write your loan agreement. You can find examples of loan agreements in many business books; just write up the same information, complete it and sign it. If you do decide to get legal advice, you can save money by drawing up the loan agreement yourself and then giving it to an attorney to redraft.

If the loan that can’t be repaid is a business loan, however, the lender receives a deduction against ordinary income and can take deductions even before the loan becomes totally worthless. (One catch: The IRS takes a very narrow view of what qualifies as a business loan. To qualify as a business loan, the loan would have to be connected to the lender’s business.) This will be difficult, so consult an accountant about the best way to structure the loan for maximum tax benefits to both parties.

Making your relative a shareholder doesn’t mean you’ll have to put up with Mom or Pop in the business. Depending on your company’s organizational structure, your friend or relative can be a silent partner if your company is set up as a partnership, or a silent shareholder if you are organized as an S corporation or limited liability company.

Keep ’Em HappyEven with every detail documented, your responsibilities are far from over. Don’t make assumptions or take people for granted just because they are friends or family members. Communication is key.

If your relative or friend is not actively involved in the business, make sure you contact him or her once every month or two to explain how the business is going. “When people invest in small businesses, it often becomes sort of their pet project,” says McKeever. “It’s important to take the time to keep them informed.”

And, of course, there are the payments. Though friends or relatives who invest in your business understand the risks, you must never take the loan for granted. “Don’t be cavalier about paying the money back,” McKeever says. “That kind of attitude could ruin the relationship.”

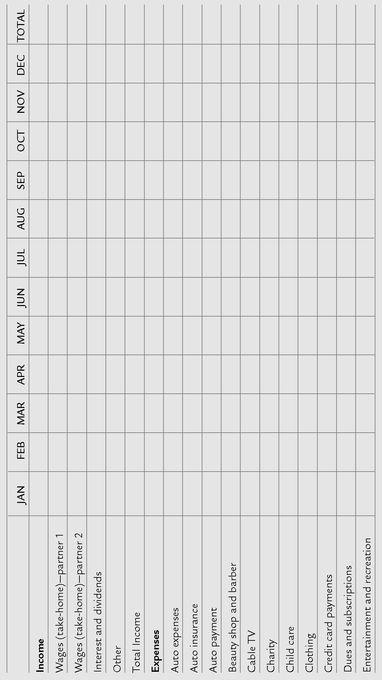

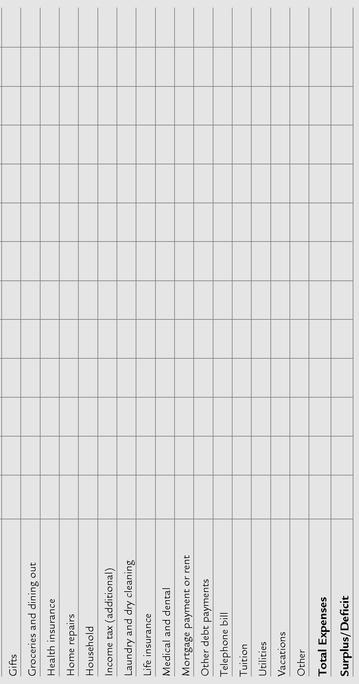

How Much Is Enough?Before you begin planning for the cash needs of your business, you must figure out how much money you will need to live on for the first six to 12 months of your business’s operation. The best way to accomplish this is to create a budget that shows where you spent your money in the past 12 months. Make sure you look over the whole 12-month period, because expenses often change a lot from month to month. When creating the schedule, be on the lookout for expenses that could be reduced or eliminated if necessary. Use the form starting on page 190 to create your own budget.

Monthly Budget

chapter 13

NOTHING VENTURED, NOTHING GAINED

How To Find and Attract Investors

N

o matter what type of financing source you approach—a bank, a venture capitalist or your cousin Lenny—there are two basic ways to finance a business: equity financing and debt financing. In equity financing, you receive capital in exchange for part ownership of the company. In debt financing, you receive capital in the form of a loan, which must be paid back. This chapter explains various types of equity financing; the following chapter explains debt financing.

Equity Basicso matter what type of financing source you approach—a bank, a venture capitalist or your cousin Lenny—there are two basic ways to finance a business: equity financing and debt financing. In equity financing, you receive capital in exchange for part ownership of the company. In debt financing, you receive capital in the form of a loan, which must be paid back. This chapter explains various types of equity financing; the following chapter explains debt financing.

Equity financing can come from various sources, including venture capital firms and private investors. Whichever source you choose, there are some basics you should understand before you try to get equity capital. An investor’s “share in your company” comes in various forms. If your company is incorporated, the investor might bargain for shares of stock. Or an investor who wants to be involved in the management of the company could come in as a partner.

AHA!One entrepreneur who wanted to open a restaurant got a list of potential investors by attending all the grand openings of restaurants in the area where he wanted to locate. By asking for the names of people who invested in those restaurants, he soon had enough contact names to finance his own business.

Other books

The Sperm Donor’s Daughter and Other Tales of Modern Family by Kathryn Trueblood

Where The Flag Floats by Grant, D C

Music of the Soul by Katie Ashley

Barbarian's Soul by Kayse, Joan

Made by Hand by Mark Frauenfelder

The Cage by Ethan Cross

Pull Me Closer (Suits in Pursuit) by Kelley, Lauren H.

Dorothy on the Rocks by Barbara Suter

Interim Goddess of Love by Mina V. Esguerra

The Color Of Love: A BWWM Billionaire Alpha Male Romance by BWWM Club, Alia Thomas