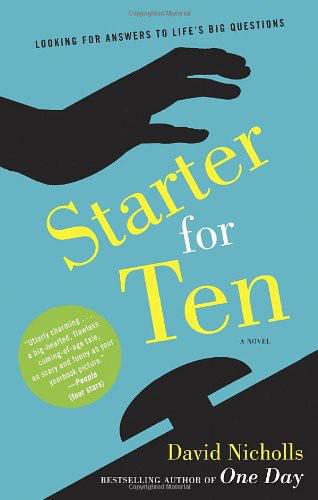

Starter For Ten

Authors: David Nicholls

Tags: #Humor, #Young Adult, #Adult, #Contemporary

To Ann and Alan Nicholls.

And Hannah, of course.

She knew this type very well - the vague aspirations, the mental disorder, the familiarity with the outside of books...

E.M. Forster, Howards End

QUESTION: Stepson to Robert Dudley and onetime favourite of Elizabeth I, which nobleman led a poorly planned and unsuccessful revolt against the Queen, and was subsequently executed in 1601?

ANSWER: Essex.

All young people worry about things, it's a natural and inevitable part of growing up, and at the age of sixteen my greatest anxiety in life was that I'd never again achieve anything as good, or pure, or noble, or true, as my O-level results. I didn't make a big deal about them at the time of course; I didn't frame the certificates or anything weird like that, and I won't go into the actual grades here, because then it just gets competitive, but I definitely liked having them; Qualifications. Sixteen years old, and the first time I'd ever felt qualified for anything. Of course, all that was a long, long time ago. I'm eighteen now, and I like to think I'm a lot wiser and cooler about these things. So my A-levels are, comparatively, no big deal. Besides, the notion that you can somehow quantify intelligence by some ridiculous, antiquated system of written examinations is obviously specious. Having said that, they were Langley Street Comprehensive School's best A-level results of 1985, the best for fifteen years in fact, three As and a B, that's 19 points - there, I've said it now - but I really, honestly don't believe that's particularly relevant, I just mention them in passing. And anyway, compared to other qualities, like physical courage, or popularity, or good looks, or clear skin, or an active sex-life, just knowing a whole load of stuff isn't actually that important.

But like my dad used to say, the crucial thing about an education is the opportunity that it brings, the doors it opens, because otherwise knowledge, in and of itself, is a blind alley, especially from where I'm sitting, here, on a late September Wednesday afternoon, in a factory that makes toasters.

I've spent the holiday working in the despatch department of Ashworth Electricals, which means I'm responsible for putting the toasters in their boxes before they're sent out to the retailers. Of course, there are only so many ways you can put a toaster in a box, so it's been a pretty dull couple of months over all, but on the plus side it's Ł1.85 an hour, which isn't bad, and as much toast as you can eat. As it's my last day here, I've been keeping an eye open for the surreptitious passing-round of the goodbye card and the collection for the leaving present, and waiting to find out which pub we're going to for farewell drinks, but it's 6.15 now, so I think it's probably safe to assume that everyone's just gone home.

Just as well though, because I had other plans anyway, so I get my stuff, grab a handful of biros and a roll of sellotape from the stationery cupboard and head off to the pier, where I'm meeting Spencer and Tone.

At 2,360 yards, or 2.158 kilometres, Southend pier is officially the longest pier in the world. This is probably a little bit too long, to be honest, especially when you're carrying a lot of lager. We've got twelve large cans of Skol, sweet-and-sour pork balls, special-fried-rice and a portion of chips with curry sauce - flavours from around the world - but by the time we reach the end of the pier, the lagers are warm and the takeaway's cold. As this is a special celebration Tone's also had to lug his ghetto-blaster, which is the size of a small wardrobe and, it's fair to say, will probably never blast a ghetto, unless you count Shoeburyness. At the moment it's playing Tone's homemade compilation The Best Of The Zep as we settle down on a bench at the end and watch as the sun sets majestically over the petrol refinery.

'You're not going to turn into a wanker, are you?' says Tone, opening a can of lager.

'What d'you mean?'

'He means you're not going to get all studenty on us,' says Spencer.

'Well, I am a student. I mean, I will be, so . . .'

'No, but I mean you're not going to get all twatty and up-your-own-arse and come home at Christmas in a gown, talking Latin and saying "one does" and "one thinks" and all that . . .'

'Yeah, Tone, that's exactly what I'm going to do.'

'Well don't. Because you're enough of a twat already without becoming even more of a twat.'

I get called 'twat' a lot by Tone, either 'twat' or 'gaylord', but the trick is to make a sort of linguistic adjustment, and try to think of it as a term of affection, in the same way as some couples say 'dear' or 'darling'. Tone's just started a job in the warehouse in Currys, and is starting to develop a nice little sideline in knocked-off portable hi-fis, like the one we're listening to now. It's his Led Zeppelin tape too; Tone likes to call himself 'a Metallist', which sounds more vocational than 'rocker' or 'heavy-metal fan'. He dresses like a Metallist too; lots of light blue denim, and long, flicked-back lustrous blond hair, like an effeminate Viking. Tone's hair is actually the only effeminate thing about him. This is, after all, a man steeped in brutal violence. The mark of a successful evening out with Tone is that you get home without having had your head flushed down a toilet.

It's 'Stairway to Heaven' now. 'Do we have to listen to this fucking hippie bollocks, Tone?' says Spencer.

'This is The Zep, Spence.'

'I know it's The Zep, Tone, that's why I want you to turn the fucking thing off.'

'But The Zep rule.'

'Why? Because you say they rule?'

'No, because they were a massively influential and important band.'

'They're singing about pixies, Tony. It's embarrassing . . .'

'Not pixies . . .'

'Elves then,' I say.

'It's not just pixies and elves, it's Tolkien, it's literature . . .' Tone loves that stuff; books with maps in the front, and cover illustrations of big, scary women in chain-mail underwear, holding broad-swords, the kind of woman that, in an ideal world, he'd marry. Which, in Southend, is actually a lot more feasible than you'd think.

'What's the difference between a pixie and an elf anyway?' asks Spencer.

'Dunno. Ask Jackson, he's the cunt with the qualifications.'

The dunno, Tone,' I say.

The guitar solo has kicked in and Spencer's wincing now. 'Does it ever end or does it just go on and on and on and on . . .'

'It's seven minutes, thirty-two seconds of pure genius.'

'Pure torture,' I say. 'Why's it always your choice, anyway?'

'Because it's my ghetto-blaster . . .'

'Which you nicked. Technically, it still belongs to Currys.'

'Yeah, but I buy the batteries . . .'

'No, you nick the batteries . . .'

'Not these, I bought these.'

'So how much were the batteries then?'

'One pound ninety-eight.'

LSo if I give you sixty-six pence, can we have something decent on?'

'What, like Kate Bush? Alright then, Jackson, let's put some Kate Bush on then, all have a really good time listening to Kate Bush, all have a really, really good dance and a singalong to Kate Bush . . .' And while Tone and I are bickering, Spencer leans over to the ghetto-blaster, nonchalantly ejects The Best Of The Zep, and skims it far out to sea.

Tone shouts 'Oi!' and throws his can of lager after him as they both run off down the pier. It's best not to get too involved in the fights. Tone tends to get a little bit out of control, possessed by the spirit of Odin or something, and if I get involved it will inevitably end with Spencer sitting on my arms while Tone farts in my face, so I just sit very still, drink my lager, and watch Tone trying to hoist Spencer's legs over the pier railings.

Even though it's September, there's the beginning of a damp chill in the evening air, a sense of summer coming to an end, and I'm glad I wore my army-surplus greatcoat. I've always hated summer; the way the sun shines on the TV screen in the afternoons, and the relentless pressure to wear T-shirts and shorts. I hate T-shirt and shorts. If I were to stand outside a chemist in T-shirt and shorts, I guarantee some old dear would try and put a coin in the top of my head.

No, what I'm really looking forward to is the autumn, to kicking through leaves on the way to a lecture, talking excitedly about the Metaphysical Poets with a girl called Emily, or Katherine, or Francois, or something, with black opaque woolly tights and a Louise Brooks bob, then going back to her tiny attic room and making love in front of her electric bar fire. Afterwards we'll read T.S.Eliot aloud and drink fine vintage port out of tiny little glasses while listening to Miles Davis. That's what I imagine it's going to be like, anyway. The University Experience. I like the word experience. It makes it sound like a ride at Alton Towers. The fight's over, and Tone is burning off his excess aggression by throwing sweet-and-sour pork-balls at the seagulls. Spencer walks back, tucking his shirt in, sits down next to me and opens another can of lager. Spencer really has a way with a can of lager; watching him, you could almost imagine he's drinking from a martini glass.

Spencer's the person I'll miss the most. He isn't going to university, even though he's easily the cleverest person I've ever met, as well as the best-looking, and the hardest, and the coolest. I wouldn't tell him any of that of course, because it would sound a bit creepy, but there's no need as he clearly knows it, anyway. He could have gone to university if he'd really wanted to, but he fouled up his exams; not deliberately as such, but everyone could see him doing it. He was sat at the desk next to me for the English Set-text Paper, and you could tell by the movements of his pen that he wasn't writing, he was drawing. For his Shakespeare question he drew The Merry Wives of Windsor, and for Poetry he did a picture entitled 'Wilfred Owen Experiences the Horror of the Trenches at First Hand'. I kept trying to catch his eye, so I could give him a friendly 'hey, come on mate' kind of look, but he just kept his head down, drawing away, and then after an hour he got up, and walked out, winking at me on the way; not a cocky wink, a slightly tearful, red-eyed wink, like a plucky tommy on his way to the firing squad.

After that, he just stopped coming in for exams. In private, the phrase 'nervous breakdown' was mentioned a couple of times, but Spencer's far too cool to have a nervous breakdown. Or if he did, he'd make the nervous breakdown seem cool. The way I see it, that whole Jack Kerouac, tortured existential thing is fine up to a point, but not if it's going to interfere with your grades.

'So what are you going to do, Spence?'

He narrows his eyes, looks at me. 'What d'you mean, "Jo"?'

'You know. Job-wise.'

'I've got a job.' Spencer's signing on, but also working cash-in-hand at the all-night petrol station on the A127.

'I know you've got a job. But in the future . . .'

Spencer looks out across the estuary, and I start to regret raising the subject.

'Your problem, Brian my friend, is that you underestimate the appeal of life in an all-night petrol station. I get to eat as much confectionery as I want. Road atlases to read. Interesting fumes to inhale. Free wine glasses . . .' He takes a long swig of lager, and looks for a way to change the subject. Reaching into his Harrington, he pulls out a cassette tape with a handwritten inlay card: 'I made this for you. So you can play it in front of your new university friends, trick them into thinking you've got taste.'

I take the tape, which has 'Bri's College Compilation' written down the spine in careful 3-D capitals. Spencer's a brilliant artist.

'This is fantastic Spencer, thanks mate . . .'

'Alright, Jackson, it's only a sixty-nine pee tape from the market, no need to cry about it.' He says that, but we're both aware that a ninety-minute compilation tape represents a good three hours of work, more if you're going to design an inlay card. 'Put it on will you? Before the muppet comes back.'

I put the tape in, press play, and it's Curtis Mayfield singing 'Move On Up'. Spencer was a mod, but has moved on to vintage soul; Al Green, Gil Scott-Heron, that kind of thing. Spencer's so cool he even likes jazz. Not just Sade and The Style Council either; proper jazz, the irritating, boring stuff. We sit and listen for a while. Tone's now trying to wheedle money out of the telescopes with the flick-knife he bought on a school trip to Calais, and Spencer and I watch like the indulgent parents of a child with acute behavioural problems.

'So are you coming back at weekends?' asks Spencer.

The don't know. I expect so. Not every weekend.'

'Make sure you do though, won't you? Otherwise I'll just be stuck here on my own with Conan The Barbarian . . .' and Spencer nods towards Tone, who's now taking running jumps and drop-kicking the telescope.

'Shouldn't we make a toast or something?' I say.

Spencer curls his lip 'A toast? What for?'

'You know - to the future or something?'

Spencer sighs, and taps his can against mine. 'To the future. Here's hoping your skin clears up.'

'Piss off, Spencer,' I say.

'Piss off, Brian,' he says, but laughing.

By the time we're on to the last cans of lager, we're pretty drunk, so we lie on our backs, not saying anything, just listening to the sea and Otis Redding singing 'Try A Little Tenderness', and on this clear late summer night, looking up at the stars, with my best mates either side of me, it feels as if real life is beginning at last, and that absolutely everything is possible.