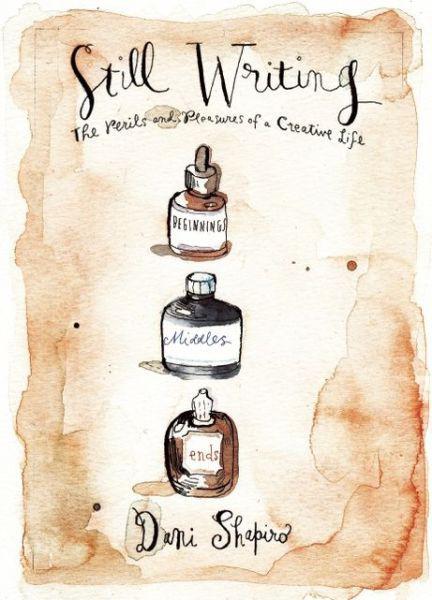

Still Writing: The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life

Read Still Writing: The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life Online

Authors: Dani Shapiro

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Writing

The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life

Also by Dani Shapiro

Devotion

Black & White

Family History

Slow Motion

Picturing the Wreck

Fugitive Blue

Playing with Fire

Sti l l Wri t in g

The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life

By Dani Shapiro

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

Copyright © 2013 by Dani Shapiro

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials.

Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or [email protected].

Printed in the United States of America

Published Simultaneously in Canada

ISBN: 978-0-8021-2140-0

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

In Memory of Grace Paley

“I have to get lost so I can invent some way out.”

—David Salle, “41 False Starts”

The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life

I’ve heard it said that everything you need to know about life can be learned from watching baseball. I’m not what you’d call a sports fan, so I don’t know if this is true, but I do believe in a similar philosophy, which is that everything you need to know about life can be learned from a genuine and ongoing attempt to write.

At least this has been the case for me.

I have been writing all my life. Growing up, I wrote in soft-covered journals, in spiral-bound notebooks, in diaries with locks and keys. I wrote love letters and lies, stories and missives. When I wasn’t writing, I was reading. And when I wasn’t writing or reading, I was staring out the window, lost in thought. Life was elsewhere—I was sure of it—and writing was what took me there. In my notebooks, I escaped an unhappy and lonely childhood. I tried to make sense of myself.

I had no intention of becoming a writer. I didn’t know that 1

Dani Shapiro

becoming a writer was possible. Still, writing was what saved me. It presented me with a window into the infinite. It allowed me to create order out of chaos.

Of course, there’s a huge difference between the scribblings of a young girl in her journals—I would never get out from under my bed if anyone were ever to read them—and the sustained, grown-up work of crafting something resonant and lasting, a story that might shed light on our human condition. “The good writer,” Ralph Waldo Emerson noted in his journal, “seems to be writing about himself, but has his eye always on that thread of the universe which runs through himself and all things.”

Sitting down to write isn’t easy. A few years ago, a local high school asked me if a student who is interested in becoming a writer might come and observe me. Observe me! I had to decline. I couldn’t imagine what the poor student would think, watching me sit, then stand, sit again, decide that I needed more coffee, go downstairs and make the coffee, come back up, sit again, get up, comb my hair, sit again, stare at the screen, check e-mail, stand up, pet the dog, sit again

.

.

.

You get the picture.

The writing life requires courage, patience, persistence, empathy, openness, and the ability to deal with rejection. It requires the willingness to be alone with oneself. To be gentle with oneself. To look at the world without blinders on. To observe and withstand what one sees. To be disciplined, and 2

Still Writing

at the same time, take risks. To be willing to fail—not just once, but again and again, over the course of a lifetime. “Ever tried, ever failed,” Samuel Beckett once wrote. “No matter.

Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” It requires what the great editor Ted Solotoroff once called

endurability

. It is this quality, most of all, that I think of when I look around a classroom at a group of aspiring writers. Some of them will be more gifted than others. Some of them will be driven, ambitious for success or fame, rather than by the determination to do their best possible work. But of the students I have taught, it is not necessarily the most gifted, or the ones most focused on imminent literary fame (I think of these as short sprinters), but the ones who endure, who are still writing, decades later.

It is my hope that—whether you’re a writer or not—this book will help you to discover or rediscover the qualities necessary for a creative life. We are all unsure of ourselves. Every one of us walking the planet wonders, secretly, if we are getting it wrong. We stumble along. We love and we lose. At times, we find unexpected strength, and at other times, we succumb to our fears. We are impatient. We want to know what’s around the corner, and the writing life won’t offer us this. It forces us into the here and now. There is only this moment, when we put pen to page.

Had I not, as a young woman, discovered that I was a writer, had I not met some extraordinarily generous role models and 3

Dani Shapiro

teachers and mentors who helped me along the way, had I not begun to forge a path out of my own personal wilderness with words, I might not be here to tell this story. I was spinning, whirling, without any sense of who I was, or what I was made of. I was slowly, quietly killing myself. But after writing saved my life, the practice of it also became my teacher. It is impossible to spend your days writing and not begin to know your own mind.

The page is your mirror. What happens inside you is reflected back. You come face-to-face with your own resistance, lack of balance, self-loathing, and insatiable ego—and also with your singular vision, guts, and fortitude. No matter what you’ve achieved the day before, you begin each day at the bottom of the mountain. Isn’t this true for most of us? A surgeon about to perform a difficult operation is at the bottom of the mountain. A lawyer delivering a closing argument. An actor waiting in the wings. A teacher on the first day of school.

Sometimes we may think that we’re in charge, or that we have things figured out. Life is usually right there, though, ready to knock us over when we get too sure of ourselves. Fortunately, if we have learned the lessons that years of practice have taught us, when this happens, we endure. We fail better. We sit up, dust ourselves off, and begin again.

4

“Endings are elusive, middles are nowhere to be found, but worst of all is to begin, to begin, to begin!”

—Donald Barthelme

I grew up the only child of older parents. If I were to give you a list of all the facts of my early life that made me a writer, this one would be near the top.

Only child. Older parents.

It now almost seems like a job requirement—though back then, I wished it to be otherwise. A lonely, isolated childhood isn’t a prerequisite for a writing life, of course, but it certainly helped.

My parents were observant Jews. We kept a kosher home. On the Sabbath, from sundown on Friday evening until sundown on Saturday, we didn’t drive, we didn’t turn on lights, or the radio, or television, and I wasn’t allowed to ride my bike, or play the piano, or do homework. This left me with a lot of time to do nothing. Most Saturday mornings, I walked a half-mile to synagogue with my father while my mother stayed home with a sinus headache.

Our house was silent and spotless. Dirt, smudges, noise—

any kind of disarray would have been unthinkable. House-keepers were always quitting. No one could keep the house to my mother’s standards. Every surface gleamed. Picture frames were dusted daily. Sheets and pillowcases were ironed three times a week. My drawers were color-coordinated: blue 7

Dani Shapiro

Danskin tops perfectly folded next to blue Danskin bottoms.

The exterminator came monthly. The toxic mold guy made biannual visits. Summers, the lawn man came every few days with his mower and hedge trimmer, clipping our suburban New Jersey acre into shape.

Control was important. It wasn’t the messiness of life that we were girding ourselves against. Secrets floated through our home like dust motes in the air. Every word spoken by my parents contained within it a hidden hard kernel of what wasn’t being said. Though I couldn’t have expressed it, I knew with a child’s instincts that life was seen by both my parents as a teeming, seething, frightful hall of mirrors. Something had made them scared. They tried to protect me from themselves, from their own histories—

der kinder,

one of them would whisper harshly and they’d stop talking after I entered the room.

I loved my parents, but I didn’t want to be like them. I didn’t want to be afraid of life. The trouble was, their way was all I knew.

And so I spent my childhood straining to hear. With no siblings to distract me, I had plenty of time, and eavesdropped and snooped in every way I could devise. I lurked outside doorways, crouched on staircase landings. I fiddled with the intercom system in our house, attempting to tune in to rooms where one or both of my parents might be. I riffled through filing cabinets when my parents were out to dinner and the 8

Still Writing

babysitter was downstairs watching “The Partridge Family.” I haunted my mother’s closets—the cashmere sweaters in indi-vidual plastic garment bags, the shoes and purses in their original boxes. What was I hoping to find? A clue. A

reason

. We had telephones in almost every room, but the one in my mother’s office had a little doohickey that you could lift up, preventing anyone from picking up another extension, and listening in. I noticed that whenever my mother was on the phone, she used it. What was she saying that I wasn’t meant to hear?

I didn’t know that this spying was the beginning of my literary education. That the need to know, to discover, to peel away the surface was a training ground for who and what I would grow up to become. The idea of becoming a writer was more remote to me than becoming an astronaut. I didn’t know any writers. Our neighborhood wasn’t an artistic hot-bed. I didn’t draw parallels between the books I loved, and read every night under the covers with a flashlight, and the idea that someone—a woman, say, alone in a room, wrestling with words and thoughts and ideas—could in fact spend her life writing them.

I slunk around like a detective. I learned to hide on the staircase without making a sound. I wanted to unearth the sources of my parents’ pain, though it would be many years before I would begin to understand it. All I knew was this: life seemed sad. It seemed parched, fruitless, devoid of joy. By the 9

Dani Shapiro

time I was eleven or twelve, I began to escape into my room and to write. I discovered my imagination, where I was free of my father’s sorrow, my mother’s headaches. I was free from the sense that my parents were disappointed in each other, and from my fear that they would be disappointed in me. I was free from

der kinder!,

and the Sabbath rules. I closed and locked my bedroom door—take

that,

parents!—and I made up stories. Sometimes I wrote them as letters to friends. Sometimes I pretended every word was true.

I wondered if I might be crazy.

I had no idea that I was becoming a writer.

Here’s a short list of what not to do when you sit down to write. Don’t answer the phone. Don’t look at e-mail. Don’t go on the Internet for any reason, including checking the spelling of some obscure word, or for what you might think of as research but is really a fancy form of procrastination. Do you need to know, right this minute, the exact make and year of the car your character is driving? Do you need to know which exit on the interstate has a rest stop? Can it wait? It can almost always wait. On the list of other, less fancy procrastinations, 10