Stories for Boys: A Memoir (14 page)

Read Stories for Boys: A Memoir Online

Authors: Gregory Martin

Accountability

I CALLED MY FATHER AND WE TALKED FOR A FEW MINUTES. We didn’t argue the semantics of beg, borrow, or steal. We didn’t talk about Thanksgiving or Christmas or my birthday. We didn’t talk about how long it had been since we last talked. We didn’t talk about his new condo or the new person in his life, with whom he seemed to have much in common. We didn’t talk about science fiction or incest self-help literature. We talked about the weather in Spokane and Albuquerque.

Then I said, “I’m sorry you’ve been having such a hard time lately.”

He said, “Thank you, son. I guess it helps to just acknowledge it.”

“I think so.”

He asked how the boys were doing, and I told him about how, that morning at preschool, Evan and his best friend, Isaac, had been playing on the platform at the top of the slide, and Evan either bumped or pushed Isaac, and Isaac had fallen down the slide headfirst. Isaac’s arm was broken; Evan’s heart was broken. When I arrived to pick him up after lunch, Evan’s face was still flushed red and tear-streaked. When I asked him what happened, he had a hard time catching his breath. He couldn’t tell me. His teacher had to tell me. I asked him, “Did you push Isaac? Or was it just an accident?”

Evan didn’t answer this question, not then, not later. He just wailed. He kept saying, “I’m so sorry,” over and over.

If You Build It

I STARTED IMAGINING A HOUSE IN THE TREES. A TREEHOUSE, in the backyard. There had been talk of a treehouse for a few years. The boys wanted one. I wanted one and wanted to build one. Christine wanted me to build one because the boys wanted one. I just hadn’t gotten around to it yet, because of

blah, blah, blah

, and what with

blah, blah, blah

.

blah, blah, blah

, and what with

blah, blah, blah

.

My father built a treehouse when I was five or six years old. It wasn’t really a treehouse because it was freestanding, but we still called it a treehouse. The top deck was shrouded by branches and leaves. It was in the side yard of the house where I grew up in Lincoln, Nebraska. A host of objects, some harmless, some not, were hurled from the deck down upon suspecting and unsuspecting foes. Headquarters. Refuge. Secret hiding place. The long slow hours of afternoons. Comic books abandoned to weather. The call for dinner. The dark coming on.

IT WAS MARCH, and the days were getting warmer, up into the sixties. Oliver and Evan and I were walking the two blocks to the park in the late afternoons and early evenings. I was capable, again, of ordinary park conversation, so long as you were willing to talk with me about treehouses. I’d bought some lumber and nails and lag bolts and screws. I’d salvaged the two-by-six tongue and groove boards from the old patio cover I’d torn down the year before. The new and salvaged lumber was stacked on the back patio. I had made preliminary notes and sketches but had lost momentum somehow and re-lapsed into the procrastination phase of my creative process.

Dan was a neighborhood dad and an engineer who worked for one of the national laboratories in Albuquerque. He did something with lightwave particles, photons maybe. I didn’t have the upper division math and physics prerequisites to understand what he did, but I weathered him talking about a recent work project until I could change the subject to treehouses.

It turned out that Dan had built a treehouse a few years before. He mentioned static and dynamic loads. He’d used steel cables set at certain tensions. I said I thought you only used steel cables on suspension bridges and chair lifts at ski resorts. He looked at me and shook his head in the way that engineers always shake their heads at people with MFAs. I told him that I could just about run my tape measure so long as I didn’t have to convert fractions.

“I can loan you my blueprints, if you want,” he offered.

“You made blueprints?”

Dan had blueprint-making software, which he was willing to loan me as well.

I didn’t like blueprints. Like all women her age, Christine wanted a kitchen remodel, and I’d reluctantly glanced at some blueprints in books she’d checked out from the library. I could sometimes tell where the doors were. Nothing left me dizzy like blueprints. They never became three dimensional holograms, like the intercepted plans for the Death Star do at the end of

Return of the Jedi

.

Return of the Jedi

.

“Maybe you could just write a story about a treehouse?” Dan said unkindly.

“About not building a treehouse after all,” I said, “about giving up and failing my children and myself?”

“Right,” Dan said. “Isn’t failure one of the writer’s great subjects?”

“Engineers aren’t supposed to know that,” I said.

I left the park demoralized. I couldn’t even pretend to be alpha male of the neighborhood. Not with guys like Dan in the pack. Or Steve, an ER doctor with a beat-up truck and a motorcycle. I drove a twelve-year-old Saturn station wagon. Travis used to race mountain bikes professionally. My mountain bike didn’t have a suspension fork. DJ drank more than anyone else on poker nights but never seemed drunk and consistently won big. Mark was a teacher, like me, but he’d climbed a bunch of the fourteeners in Colorado. You didn’t get points towards alpha male by coming up with the best similes. They deducted points from the guy with the best similes. I’d been hoping that my treehouse would move me up in the standings, but there was no way my treehouse would be better than Dan’s. His treehouse probably had a wall made entirely of glass, cantilevered at an architecturally sophisticated angle. His treehouse probably had an elevator that opened onto an atrium.

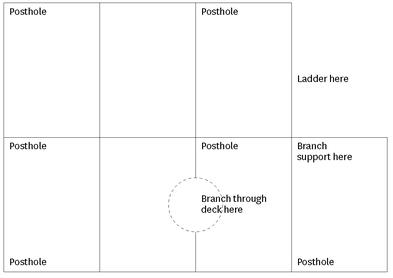

ONE EARLY WEEKEND morning, right after coffee, I put Dan mostly out of my mind. I went outside into the cool spring air and got after it. I nailed together the two-by-six floor joists. The platform was to be eight feet by nine feet. I wanted one of the branches of the tree to come up through the floor of the treehouse deck and another branch to support the platform. The rest would be supported by four-by-four posts set into holes dug three feet deep.

Out in the yard, I hammered wooden stakes in the ground where the postholes would be and ran a string between them to make sure the corners were true. I stood in the space between the strings and looked up to see where the branch of the tree would pass through the deck. This eyeballing wasn’t precise enough. In a moment of inspiration, I tied a one-half inch hex nut to a long piece of string and dropped this string from the tree branch. A plumb line! My stakes were in the right place! I went inside for a second breakfast to thunderous imaginative applause.

When I came out Evan was jumping around in the grass inside the strings. He was in his pajamas. My hex nut plumb line had become a pendulum.

“Look, Dad,” Evan said. “I’m playing in the treehouse!” And he was. The treehouse in Evan’s mind was real in the way memory is real, like the memory I have now of that time before I built a treehouse. Igor Stravinsky says in

Poetics of Music

: “Invention presupposes imagination but should not be confused with it … What we imagine does not necessarily take on concrete form and may remain in a state of virtuality; whereas invention is not conceivable apart from its actually being worked out.”

Poetics of Music

: “Invention presupposes imagination but should not be confused with it … What we imagine does not necessarily take on concrete form and may remain in a state of virtuality; whereas invention is not conceivable apart from its actually being worked out.”

Stravinsky says, “We have a duty towards music; namely, to invent it.”

I had begun to feel Stravinskian about the treehouse, a deep inner obligation, a faith that it would not be just Evan and Oliver who needed the treehouse, but other children in the neighborhood as well, children known to me and not yet known. I felt that my neighborhood itself would be a better place because of the treehouse. I had a duty towards treehouses; namely, to build one.

Evan ran around inside the strings for awhile. When he went back in the house, I cut the strings and where each stake had been, I dug a deep hole. The first foot and half went quickly; the next foot and a half took ten times as long – the soil deeper down was hard clay, but it broke up in small pieces if I just kept chipping away at it. This was a metaphor if I wanted one, but I didn’t. I didn’t want a post hole digger, either. Steve had one, but I didn’t want to ask anyone for anything or tell anyone what I was up to. Not anymore. I was all through with talk. I felt like working hard. My self-pity had melted away. I felt purposeful, attentive, focused.

At the bottom of each of these holes I set a brick. I carried the floor joist platform over from the patio and set it on the ground so that each posthole was now in a corner of the frame.

In a feat of mechanical advantage that would have made Archimedes proud, using two thin ropes each running through pulleys set high up in the tree, Oliver and Evan and I hoisted the platform slowly into the air. We tied off the ropes. The frame of the floor of our treehouse swayed in the breeze above our heads. There was cheering. Christine came out to see what was going on, and she could not quite disguise her pride in her man.

One by one we set the posts in their holes, and by inserting lag bolts through pre-drilled holes, we connected each post to the platform six feet off the ground, leaving the nuts only finger-tight, for now. We’d tighten them later, when the posts were plumb. In discussion threads all over the internet, the question of setting posts has been examined. Ready-mix concrete or compressed soil? I based my decision on the terse conviction of a Wyoming rancher. His ranch was big; he maintained a lot of fence; he couldn’t pour concrete in all those holes. Compress the soil, he said. It works.

Christine used the level to make sure each post was plumb, and with a two-by-two, Oliver and Evan I took turns tamping the dirt we kicked back in the holes. It worked and still works. Those posts ain’t going nowhere.

We untied the ropes and pulleys. We didn’t need them anymore.

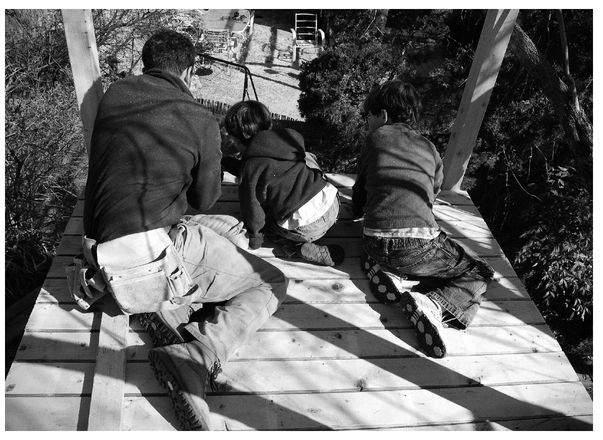

The boys wanted to get up on the frame and walk on the open joists, balance beam style. This wasn’t particularly safe, but I got my ladder and propped it against the frame. I went up and Oliver and Evan followed. Maternal exhortations reached us faintly from somewhere far below. The boys started out on their knees. Then they stood, holding on to the tree’s branch coming up through the joists. I was happy. The boys were happy. Christine was unhappy. The boys and I stayed up there a good while, growing more confident, but never just walking out with our arms outspread. The day was ending. We came down the ladder. I cleaned up the site and put my tools away. Christine made hot dogs and french fries, and we ate dinner out on the patio and looked at the frame of the floor of our house in the trees.

The next morning, I nailed and set the salvaged two-by-six tongue and groove flooring. This went fast. I left only a few inches between the emerging branch of the tree and the deck flooring, and so now when the wind blows hard, the branch sways, and the whole treehouse creaks and groans satisfyingly. The boys climbed the ladder onto the finished platform and looked around, feasting their eyes about. They could see down into each of the neighbor’s yards – north, south, and west.

The boys went back inside. I built the stud walls of the house with the two-by-sixes that I ripped into two-by-fours. I didn’t own a table saw or a chop saw, and so I did all this cutting and ripping on my Porter Cable circular saw. If I were willing to advertise this, it would certainly earn me points towards alpha male of the neighborhood. My guess was that Dan had more power tools than Norm Abram on New Yankee Workshop. I was practically a Shaker by comparison. But I kept all this to myself. I didn’t care about that anymore. I screwed in one-by-ten pine boards for siding, leaving windows all around. I notched and nailed rafters. I nailed down the pine board roof. I built a wraparound picket railing.

Other books

Crooked by Laura McNeal

A History of the Crusades-Vol 2 by Steven Runciman

Sookie 09 Dead and Gone by Charlaine Harris

The Exodus Sagas: Book III - Of Ghosts And Mountains by Jason R Jones

Slade by Victoria Ashley

Monarchy by Erasmus, Nicola

Silver Wedding by Maeve Binchy

Of Noble Chains (The Ventori Fables) by Miles, D.L.

Spirit's Release by Tea Trelawny

Garden of Darkness by Anne Frasier