Straight on Till Morning (18 page)

Read Straight on Till Morning Online

Authors: Mary S. Lovell

1931â1933

Beryl had already received some six hours of flying tuition in one of the Wilson Airways Gipsy Moths when she returned to Nairobi in June 1931. After a further two and a half hours Tom decided she was ready to go solo. This does not mean she became a fully fledged pilot â far from it. Dual instruction continued as before in a process all pilots have to endure, even today. The student follows the instructor through the various points of flying â take-off, turning, banking, climbing, stalling and landing â whilst paying particular attention to the actions of the different control surfaces upon the aeroplane's flight â ailerons, elevators, rudder and flaps. This was basic instruction to give the student the feel of the aeroplane.

In common with all student pilots Beryl had spent most of her initial training on âcircuits and bumps', for it was not until Tom was absolutely sure that she was capable of handling this procedure that he could allow her to solo. It involves taking off, circling the aerodrome in the correct pattern, and landing. It sounds simple and indeed in today's modern aircraft it is not difficult. But in 1931 at Nairobi things were not quite so easy. The runway â a dirt track â was subject to the sudden appearance of pig-holes and ant-hills and it was not unusual to have to clear it of wild animals who had wandered on to it from the Athi plains in search of water.

1

The landing technique involved executing a perfect three-pointer in which the two wheels of the undercarriage had to make contact with the ground at the precise moment that the tail skid touched down. If the aeroplane came in too fast, when the control column was pulled back to stall the machine bounced up into the air and came to rest after an embarrassing series of bumps always watched with great interest by spectators. If the speed was too slow the aeroplane would pancake heavily, often breaking the tail skid.

Gradually the instructor hands over control of the aeroplane until, confident that the pupil is able to take off, circle the aerodrome and land safely, almost casually he utters the awesome words: âI think you might be ready for a solo now, you know. Would you like to take her around?' Of course the student has been waiting for just this moment, but when it happens, the stomach tightens, and the heart turns over.

Beryl would not have been sent up alone one second sooner than Tom felt she was ready. He was an extraordinarily careful pilot and she could not have been more fortunate in having him as an instructor. He was probably one of the best pilots in the world at that time. A modest man, with a delightfully puckish sense of humour, he was precise, well educated and kind; and he believed implicitly in the future of civil aviation. While many of his generation who had learned to fly in the war now saw aeroplanes as toys, and flying as the smart thing to do, Tom had a broad vision of future civil aviation which was subsequently borne out almost exactly.

Born in Brighton in 1898, the son of an Australian who became mayor of Brighton, Tom was educated at Brighton College and at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich. Writing of his schoolday interests he recalled, âWhen Bleriot flew the Channel there was intense excitement. We all set to work to construct modelsâ¦It was this early toying with models and the opportunity which the war gave to so many of my generation that created in me the urge to fly.' He was seventeen when the war broke out but he immediately enrolled with the Royal Naval Air Service, adding a year to his age in order to be accepted. Later he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps

2

and at the end of the war he led the first British squadron into Cologne.

3

He remained in the RFC after the war ended, and then, after an inconclusive period studying law, in the early 1920s he went out to Kenya with backing from an uncle. With his brother, he started a coffee farm at Rongai. By now, though, flying was in his blood, and he spent less and less time coffee-farming and more in the air. Eventually his brother returned to England. Tom hired a full-time manager to run the farm, which was not self-supporting, got himself a commercial licence and did freelance flying work from a landing ground at the side of the Langata Road, which was later to become Nairobi West Airport (now Wilson Airport). He opened up air routes for mail deliveries in East Africa, and he saw it almost as a personal mission to establish a commercial air service there. Without any doubt his level-headed approach to flying was responsible for Beryl's competence later on.

In 1928 Tom met Mrs Florence Kerr Wilson, then nearly fifty years old and recently widowed. In the spring of 1929 Tom flew âFlorrie' to England in a Fokker Universal aircraft belonging to John Carberry, taking Archie Watkins along as the engineer. He had made the flight several times before and indeed was partly responsible for establishing the air route for civilian traffic. There were no airfields as such, for flying was not an established occupation, and proper facilities for aircraft did not become available until the African service of Imperial Airways was formally established in the early 1930s.

4

When Tom made his flight in 1929, the best one could hope for was a level piece of ground, suitable for landing and taking off, located near a refuelling depot. The Shell Oil Company were of tremendous assistance in the early days of flying, particularly over the Sudan, and would usually provide a representative with a fuel supply to hang around and wait for a pilot on a given day. If an aeroplane didn't turn up, the representative would assume the worst and instigate a search â if the pilot was lucky.

At the end of 1924 captains Tony Gladstone and Tom Twist had pioneered air transport routes by making a journey up the Nile from Cairo to Kisumu on foot to establish landing stages for the first flying-boat services,

5

and for many years civilian pilots used landing strips adjacent to these staging posts when flying between Europe and Africa. There were no proper flying maps, merely charts which had been put together based on the few flights made by pilots over the territory. Tom, Florrie Wilson and Archie accomplished their flight to London in eight days, a record time for the journey which lasted only briefly. Tom broke it later that same year.

Â

Beryl Markham, July 1936.

Â

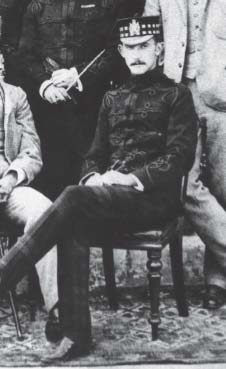

Charles Clutterbuck in the uniform of the King's Own Scottish Borderers Regiment,

circa

1895.

(Neil Potts)

Â

Paddy (the lion who attacked the ten-year-old Beryl) with his owners: Margaret and âMrs Jim' Elkington.

(Elspeth Huxley)

Â

The house which Clutterbuck built for Beryl in 1915.

Â

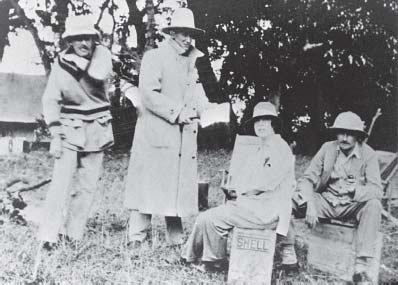

Beryl's first marriage to Jock Purves in Nairobi, October 1919.

l. to r.

Jock, Beryl, Charles Clutterbuck, Captain Lavender, Miss Eliza Milne.

Â

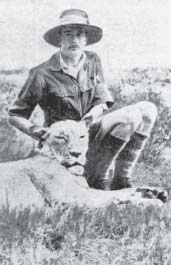

Prince Henry with the lion he killed while on safari in 1928.

(British Library)

Â

l. to r.

Bror Blixen, Edward, Prince of Wales, Denys Finch Hatton.

(Cockie Hoogterp)

Â