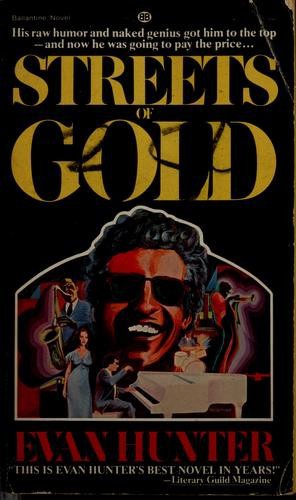

Streets of Gold

Annotation

Evan HunterIgnazio Silvio Di Palermo was born in an Italian neighborhood in New York’s East Harlem in 1926. He was born blind but was raised in a close, vivid, lusty world bounded by his grandfather’s love, his mother’s volatility, his huge array of relatives, weekly feasts, discovery of girls, the exhilaration of music and his great talent leading to a briefly idolized jazz career.

Streets of Gold

This is for my grandfather —Giuseppantonio Coppola

IThat was a hit before your Mother was bornThough she was born a long long time agoYour Mother should know — your Mother should knowSing it againJohn Lennon and Paul McCartney

I’ve been blind since birth. This means that much of what I am about to tell you is based upon the subjective descriptions or faulty memories of others, blended with an empirical knowledge of my own — forty-eight years of touching, hearing, and smelling. But paintings, rooms with objects in them, lawns of bright green, crashing seascapes, contrails across the sky, the Empire State Building, women in lace, a Japanese fan, Rebecca’s eyes — I have never seen any of these things. They come to me secondhand.

I sometimes believe, and I have no foundation of fact upon which to base this premise, that

all

experience is secondhand, anyway. Even my grandfather’s arrival in America must have been colored beforehand by the things he had heard about this country, the things that had been described to him in Italy before he decided to come. Was he truly seeing the new land with his own eyes? Or was that first glimpse of the lady in the harbor — he has never mentioned her to me, I only assume that the first thing all arriving immigrants saw was the Statue of Liberty — was that initial sighting his

own

, or was there a sculptured image already in his head, chiseled there by Pietro Bardoni in his expensive American clothes, enthusiastically selling the land of opportunities where gold was in the streets to be picked up by any man willing to work, himself talced and splendored evidence of the riches to be mined.

all

experience is secondhand, anyway. Even my grandfather’s arrival in America must have been colored beforehand by the things he had heard about this country, the things that had been described to him in Italy before he decided to come. Was he truly seeing the new land with his own eyes? Or was that first glimpse of the lady in the harbor — he has never mentioned her to me, I only assume that the first thing all arriving immigrants saw was the Statue of Liberty — was that initial sighting his

own

, or was there a sculptured image already in his head, chiseled there by Pietro Bardoni in his expensive American clothes, enthusiastically selling the land of opportunities where gold was in the streets to be picked up by any man willing to work, himself talced and splendored evidence of the riches to be mined.

The villagers of Fiormonte, in the fifth year of their misery since

la fillossera

struck the grape, must have listened in awe-struck wonder as Bardoni used his hands and his deep Italian baritone voice to describe New York, with its magnificent buildings and esplanades, food to be had for pennies a day (food!), and gold in the streets, gold to shovel up with your own two hands. He was speaking figuratively, of course. My grandfather later told me no one believed there was

really

gold in the streets, not gold to be mined, at least. The translation they made was that the streets were

paved

with gold; they had, some of them, been to Pompeii — or most certainly to Naples, which lay only 125 kilometers due west — and they knew of the treasures of ancient Rome, knew that the statues had been covered with gold leaf, knew that even common hairpins had been fashioned of gold, so why not streets paved with gold in a nation that surely rivaled the Roman Empire so far as riches were concerned? It was entirely conceivable. Besides, when a man is starving, he is willing to believe anything that costs him nothing.

la fillossera

struck the grape, must have listened in awe-struck wonder as Bardoni used his hands and his deep Italian baritone voice to describe New York, with its magnificent buildings and esplanades, food to be had for pennies a day (food!), and gold in the streets, gold to shovel up with your own two hands. He was speaking figuratively, of course. My grandfather later told me no one believed there was

really

gold in the streets, not gold to be mined, at least. The translation they made was that the streets were

paved

with gold; they had, some of them, been to Pompeii — or most certainly to Naples, which lay only 125 kilometers due west — and they knew of the treasures of ancient Rome, knew that the statues had been covered with gold leaf, knew that even common hairpins had been fashioned of gold, so why not streets paved with gold in a nation that surely rivaled the Roman Empire so far as riches were concerned? It was entirely conceivable. Besides, when a man is starving, he is willing to believe anything that costs him nothing.

Geography is not one of my strongest subjects. I have been to Italy many times, the last time in 1970, on a joint pilgrimage — to visit the town where my grandfather was born and to visit the grave where my brother is buried. I know that Italy is shaped like a boot; I have traced its outline often enough on Braille maps. And I know what a boot looks like. That is to say, I have lingeringly passed my hands over the configurations of a boot, and I have formed an image of it inside my head, tactile, reinforced by the rich scent of the leather and the tiny squeaking sounds it made when I tested the flexibility of this thing I held, this object to be cataloged in my brain file along with hundreds and thousands of other objects I had never seen — and will never see. The way to madness is entering the echo chamber that repeatedly resonates with doubt: is the image in my mind the

true

image? Or am I feeling the elephant’s trunk and believing it looks like a snake? And anyway, what does a snake look like? I believe I know. I am never quite sure. I am not quite sure of anything I describe because there is no basis for comparison, except in the fantasy catalog of my mind’s eye. I am not even sure what I myself look like.

true

image? Or am I feeling the elephant’s trunk and believing it looks like a snake? And anyway, what does a snake look like? I believe I know. I am never quite sure. I am not quite sure of anything I describe because there is no basis for comparison, except in the fantasy catalog of my mind’s eye. I am not even sure what I myself look like.

Rebecca once told me, “You just miss looking dignified, Ike.”

And a woman I met in Los Angeles said, “You just miss looking shabby.”

Rebecca’s words were spoken in anger. The Los Angeles lady, I suppose, was putting me down — though God knows why she felt any need to denigrate a blind man, who would seem vulnerable enough to even the mildest form of attack and therefore hardly a worthy victim. We later went to bed together in a Malibu motel-cum-Chinese restaurant, where the aftertaste of moo goo gai pan blended with the scent of her perfumed breasts and the waves of the Pacific crashed in against the pilings and shook the room and shook the bed. She wore a tiny gold cross around her neck, a gift from a former lover; she would not take it off.

For the record (who’s counting?), my eyes are blue. I am told. But what is blue? Blue is the color of the sky. Yes, but

what

is blue? It is a cool color, Ah, yes, we are getting closer. The radiators in the apartment we lived in on 120th Street were usually cool if not downright frigid. Were the radiators blue? But sometimes they became sizzling hot, and red has been described to me as a hot color, so were the radiators red when they got hot? Rebecca has red hair and green eyes. Green is a cool color also. Are green and blue identical? If not, how do they differ? I know the smell of a banana, and I know the shape of it, but when it was described to me as yellow, I had no concept of yellow, could form no clear color image. The sun is yellow, I was told. But the sun is hot; doesn’t that make it red? No, yellow is a much cooler color. Oh. Then is it like blue? Impossible. The only color I know is black. I do not have to have that described to me. It sits behind my dead blue eyes.

what

is blue? It is a cool color, Ah, yes, we are getting closer. The radiators in the apartment we lived in on 120th Street were usually cool if not downright frigid. Were the radiators blue? But sometimes they became sizzling hot, and red has been described to me as a hot color, so were the radiators red when they got hot? Rebecca has red hair and green eyes. Green is a cool color also. Are green and blue identical? If not, how do they differ? I know the smell of a banana, and I know the shape of it, but when it was described to me as yellow, I had no concept of yellow, could form no clear color image. The sun is yellow, I was told. But the sun is hot; doesn’t that make it red? No, yellow is a much cooler color. Oh. Then is it like blue? Impossible. The only color I know is black. I do not have to have that described to me. It sits behind my dead blue eyes.

My hair is blond. Yellow, they say. Like a banana. (Forget it.) I can only imagine that centuries back, a Milanese merchant (must have been a Milanese, don’t you think? It couldn’t have been a

Viking

) wandered down into southern Italy and displayed his silks and brocades to the gathered wide-eyed peasants, perhaps’ hawking a bit more than his cloth, Milanese privates securely and bulgingly contained in northern codpiece; the girls must have giggled. And one of them, dark-eyed, black-haired, heavily breasted, short and squat, perhaps later wandered off behind the grapes with this tall, handsome northern con man, where he lifted her skirts, yanked down her knickers, explored the black and hairy bush promised by her armpits, and probed with northern vigor the southern ripeness of her quim, thereupon planting within her a few thousand blond, blue-eyed (blind?) genes that blossomed centuries later in the form of yours truly, Dwight Jamison.

Viking

) wandered down into southern Italy and displayed his silks and brocades to the gathered wide-eyed peasants, perhaps’ hawking a bit more than his cloth, Milanese privates securely and bulgingly contained in northern codpiece; the girls must have giggled. And one of them, dark-eyed, black-haired, heavily breasted, short and squat, perhaps later wandered off behind the grapes with this tall, handsome northern con man, where he lifted her skirts, yanked down her knickers, explored the black and hairy bush promised by her armpits, and probed with northern vigor the southern ripeness of her quim, thereupon planting within her a few thousand blond, blue-eyed (blind?) genes that blossomed centuries later in the form of yours truly, Dwight Jamison.

My maiden name is Ignazio Silvio Di Palermo.

Di Palermo means

of

Palermo or

from

Palermo, which is where my father’s ancestors worked and died. All except my father’s father, who came to America to dig out some of the gold in them thar streets, and ended up as a street cleaner instead, pushing his cart and shoveling up the golden nuggets dropped by horses pulling streetcars along First Avenue. Ironically, he was eventually run over by a streetcar. It was said he was drunk at the time, but a man who comes to shovel gold and ends up shoveling shit is entitled to a drink or two every now and then. I never met the man. He was killed long before I was born. The grandfather I speak of in these pages was my mother’s father. From my father’s father, I inherited only my name, identical to his, Ignazio Silvio Di Palermo. Or, if you prefer, Dwight Jamison.

of

Palermo or

from

Palermo, which is where my father’s ancestors worked and died. All except my father’s father, who came to America to dig out some of the gold in them thar streets, and ended up as a street cleaner instead, pushing his cart and shoveling up the golden nuggets dropped by horses pulling streetcars along First Avenue. Ironically, he was eventually run over by a streetcar. It was said he was drunk at the time, but a man who comes to shovel gold and ends up shoveling shit is entitled to a drink or two every now and then. I never met the man. He was killed long before I was born. The grandfather I speak of in these pages was my mother’s father. From my father’s father, I inherited only my name, identical to his, Ignazio Silvio Di Palermo. Or, if you prefer, Dwight Jamison.

My father’s name is Jimmy, actually Giacomo, which means James in Italian; are you getting the drift? Jamison, James’s son. That’s where I got the last name when I changed it legally in 1955. The first name I got from Dwight D. Eisenhower, who became President of these United States in 1953. The Dwight isn’t as far-fetched as it may seem at first blush. I have never been called Ignazio by anyone but my grandfather. As a child, I was called Iggie. When I first began playing piano professionally, I called myself Blind Ike. My father liked the final name I picked for myself, Dwight Jamison. When I told him I was planning to change my name, he came up with a long list of his own, each name carefully and beautifully hand lettered, even though he realized I would not be able to see his handiwork. He was no stranger to name changes. When he had his own band back in the twenties, thirties, and forties, he called himself Jimmy Palmer.

There is in America the persistent suspicion that if a person changes his name, he is most certainly a wanted desperado. And nowhere is there greater suspicion of, or outright animosity for, the name-changers than among those who steadfastly

refuse

to change their names. Meet a Lipschitz or a Mangiacavallo, a Schliephake or a Trzebiatowski who have stood by those hot ancestral guns, and they will immediately consider the name-changer a deserter at best or a traitor at worst. I say fuck you, Mr. Trzebiatowski. Better you should change it to Trevor. Or better you should mind your own business.

refuse

to change their names. Meet a Lipschitz or a Mangiacavallo, a Schliephake or a Trzebiatowski who have stood by those hot ancestral guns, and they will immediately consider the name-changer a deserter at best or a traitor at worst. I say fuck you, Mr. Trzebiatowski. Better you should change it to Trevor. Or better you should mind your own business.

For reasons I can never fathom, the fact that I’ve changed my name is of more fascination to anyone who’s ever interviewed me (I am too modest to call myself famous, but whenever I play someplace, it’s a matter of at least some interest, and if you don’t know who I am, what can I tell you?) — a subject more infinitely fascinating than the fact that I’m a blind man who happens to be the best jazz pianist who ever lived, he said modestly and self-effacingly, and not without a touch of shabby dignity. No one ever asks me how it feels to be blind. I would be happy to tell them. I am an expert on being blind. But always, without fail, The Name.

“How did you happen upon the name Dwight Jamison?”

“Well, actually, I wanted to use another name, but someone already had it.”

“Ah, yes? What

was

the other name?”

was

the other name?”

“Groucho Marx.”

The faint uncertain smile (I can sense it, but not see it), the moment where the interviewer considers the possibility that this wop entertainer — talented, yes, but only a wop, and only an entertainer — may somehow be blessed with a sense of humor. But is it possible he really considered calling himself Groucho Marx?

“No, seriously, Ike, tell me” — the voice confidential now — “

why

did you decide on Dwight Jamison?”

why

did you decide on Dwight Jamison?”

“It had good texture. Like an augmented eleventh.”

“Oh. I see, I see. And what is your

real

name?”

real

name?”

“My real name has been Dwight Jamison since 1955. That’s a long, long time.”

“Yes, yes, of course, but what is your

real

name?” (Never “was,” notice. In America, you can never lose your real name. It “is” always your real name.) “What is your real name? The name you were born with?”

real

name?” (Never “was,” notice. In America, you can never lose your real name. It “is” always your real name.) “What is your real name? The name you were born with?”

“Friend,” I say, “I was born with yellow hair and blue eyes that cannot see. Why is it of any interest to you that my

real

name was Ignazio Silvio Di Palermo?”

real

name was Ignazio Silvio Di Palermo?”

“Ah, yes, yes. Would you spell that for me, please?”

I changed my name because I no longer wished to belong to that great brotherhood of

compaesani

whose sole occupation seemed to be searching out names ending in vowels. (Old Bronx joke: What did Washington say when he was crossing the Delaware? “

Fá ’no cazzo di freddo qui!”

And what did his boatman reply? “

Pure tu sei italiano?”

Translated freely, Washington purportedly said, “Fucking-A cold around here,” and his boatman replied, “

You’re

Italian, too?”) My mother always told me I was a Yankee, her definition of Yankee being a third-generation American, her arithmetic bolstered by the undeniable fact that

her

mother (but not her father) was born here, and she herself was born here, and I was certainly born here, ergo Ignazio Silvio Di Palermo, third-generation Yankee Doodle Dandy. My mother was always quick to remind me that

she

was American. “I’m American, don’t forget.” How

could

I forget, Mama darling, when you told me three and four times a day? “I’m American, don’t forget.”

compaesani

whose sole occupation seemed to be searching out names ending in vowels. (Old Bronx joke: What did Washington say when he was crossing the Delaware? “

Fá ’no cazzo di freddo qui!”

And what did his boatman reply? “

Pure tu sei italiano?”

Translated freely, Washington purportedly said, “Fucking-A cold around here,” and his boatman replied, “

You’re

Italian, too?”) My mother always told me I was a Yankee, her definition of Yankee being a third-generation American, her arithmetic bolstered by the undeniable fact that

her

mother (but not her father) was born here, and she herself was born here, and I was certainly born here, ergo Ignazio Silvio Di Palermo, third-generation Yankee Doodle Dandy. My mother was always quick to remind me that

she

was American. “I’m American, don’t forget.” How

could

I forget, Mama darling, when you told me three and four times a day? “I’m American, don’t forget.”

In Sicily, where I went to find my brother’s grave, your first son’s grave, Mom, the cab driver told me how good things were in Italy these days, and then he said to me, “America is

here

now.”

here

now.”

Maybe it

is

there.

is

there.

One thing I’m sure of.

It isn’t

here

.

here

.

And maybe it never was.

Other books

Matahombres by Nathan Long

At His Mercy by Alison Kent

Owner 03 - Jupiter War by Neal Asher

Thrive by Rebecca Sherwin

Shadows on the Ivy by Lea Wait

The Crimes of Paris: A True Story of Murder, Theft, and Detection by Dorothy Hoobler, Thomas Hoobler

A Second Chance With Emily by Alyssa Lindsey

Midnight Magic by Shari Anton

Red Dirt Rocker by Jody French

Succubus, Interrupted by Jill Myles