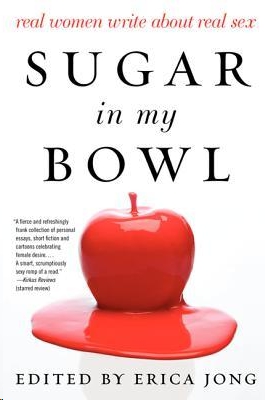

Sugar in My Bowl

Authors: Erica Jong

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Sexuality, #Literary Collections, #Essays

SUGAR IN MY BOWL

Real Women Write About Real Sex

Edited by

ERICA JONG

Dedication

For BJG and her brothers

when they grow up

Epigraph

Tired of bein’ lonely, tired of bein’ blue,

I wished I had some good man, to tell my troubles to

Seem like the whole world’s wrong, since my man’s been gone

I need a little sugar in my bowl,

I need a little hot dog, on my roll

I can stand a bit of lovin’, oh so bad,

I feel so funny, I feel so sad

—“I NEED A LITTLE SUGAR IN MY BOWL,”

BESSIE SMITH, 1931

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction - Erica Jong

A Fucking Miracle - Elisa Albert

Worst Sex - Gail Collins

Peekaboo I See You - Anne Roiphe

Prude - Jean Hanff Korelitz

Sex with a Stranger - Susan Cheever

Everything Must Go: A Short Story - Jennifer Weiner

Love Rollercoaster 1975 - Susie Bright

Absolutely Dangerous - Linda Gray Sexton

The One Who Breaks My Heart - Rosemary Daniell

Do I Own You Now? - Daphne Merkin

Let’s Not Talk About Sex - Julie Klam

My Best Friend’s Boyfriend - Fay Weldon

The Diddler - J. A. K. Andres

The Dignity Channel - Jann Turner

Miss Honeypot Marries: A Short Story - Barbara Victor

Best Sex Ever: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis - Jessica Winter

Cock of My Dreams: A Graphic Fantasy - Marisa Acocella Marchetto

Cramming It All In: A Satire - Susan Kinsolving

Reticence and Fieldwork - Min Jin Lee

My First Time, Twice - Ariel Levy

Light Me Up - Margot Magowan

Herman and Margot - Karen Abbott

Somewhere I Have Never Traveled, Gladly - Meghan O’Rourke

Skin, Just Skin: A Dramatic Triologue - Eve Ensler

Reading of O - Honor Moore

Going All the Way - Liz Smith

The Man in Question - Rebecca Walker

They Had Sex So I Didn’t Have To - Molly Jong-Fast

Kiss: A Short, Short Story - Erica Jong

Acknowledgments

Contributors

About the Editor

Notes

Also by Erica Jong

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

W

hy are we so fascinated with sex? Probably because such intense feelings are involved—above all, the loss of control. Anything that causes us to lose control intrigues and enthralls. So sex is both alluring and terrifying.

Perhaps that is why assembling this anthology surprised me.

Conventional wisdom tells us that we live in a sex-saturated society where nothing is taboo anymore. Teenagers supposedly give blow jobs at the flash of a zipper. Reliable birth control and Internet mating have made casual sex ubiquitous at younger and younger ages.

So why was it that when I first started asking for contributions to this collection, some women thought they had to check with their husbands before they agreed to contribute? Or their significant others. Or their children, for goodness’ sake. (I know that one’s children positively

avoid

one’s writing—especially if they are literarily inclined themselves.)

I guess I had bought the bullshit that

everything

had changed, that

pudeur

was obsolete, that women today were wild viragos. I knew I had been in a state of palpitating terror about revealing sexual fantasy while writing

Fear of Flying,

but things were supposed to be different now (and I was usually blamed for it).

I was wrong. At least half a dozen contributors to this book would not say yes until their partners agreed.

That was the first surprise.

The next surprise was the fear some potential contributors had that they would not be taken seriously if they wrote for my anthology.

Anaïs Nin had made exactly the same argument in 1971 when I asked her why she allowed her diaries to be bowdlerized for publication: “Women who write about sex are never taken seriously as writers,” she said.

“But that’s why we must do it, Miss Nin,” I countered.

And that

is

why we must do it. We must brave the literary double standard. Doing so, we also liberate our brothers, sons, grandsons, lovers, and husbands—who now write more fiercely and honestly about women—think of David Grossman, John Irving, Jonathan Franzen, and Abraham Verghese—than even Gustave Flaubert, Leo Tolstoy, John Updike, and Philip Roth did in the past.

I admire these men. They can teach a young—or old—writer more about writing than any book purporting to teach the art of fiction. Read them and learn. The ones who came of age after literary censorship gave way in the 1950s and 1960s have plenty to teach.

When did literary censorship become obsolete? It actually happened in the United States within my own memory. I was a graduate student in eighteenth-century English literature at Columbia when suddenly

Fanny Hill, or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure

migrated from the locked rare book room to the open shelves at Butler Library. Vladimir Nabokov’s

Lolita

was published by Putnam in 1958 after several years of underground notoriety thanks to Olympia Press, Paris. And D. H. Lawrence’s

Lady Chatterley’s Lover,

first printed in Florence, Italy, in 1928. Henry Miller’s

Tropic of Cancer

was first privately published thanks to Obelisk Press in Paris in 1934 and later published in 1961 by Grove Press in the United States.

At first, writers were ecstatic. We thought we would usher in a new age of classical bacchanalia. We thought of Sappho, Aristophanes, Ovid, Juvenal, Chaucer, Shakespeare’s bawdy plays, Swift’s “unprintable” poems, and of course D. H. Lawrence and Henry Miller. And it was true that

Couples,

Portnoy’s Complaint,

and my own

Fear of Flying

promised honesty.

But it didn’t take long for

Debbie Does Dallas

to drown out

Ulysses

. Sex, once so literary and rare, got dumbed down like everything else. When published sex became ubiquitous, it also became banal. Profit triumphed over art, and pornography became as dreary as other sleazy products in a culture where everything is for sale.

Many writers began to think it was time to clean up sex. The younger generation—children of hippies and nudists—were, like my daughter, appalled by their parents’ freedom.

Why shouldn’t they be? Isn’t it our job to be appalled by our parents? Isn’t it every generation’s duty to be dismayed by the previous generation? And to assert that we are different—only to discover later that we are distressingly the same?

Nothing new under the sun. The child is mother to the woman, father to the man. Our parents once were us—and now we are them. Our parents, bless them, thought they were oh so modern.

My own artist/musician parents ran around Provincetown in the 1930s wearing nothing but their scanties (which were much less scanty than scanties are today). They were modern bohemians of the Depression Era. Their children grew up in the fabulous 1950s, when even bohemians could be affluent. And our children grew up in the 1980s, thinking Greed was Good.

Now Depression is back—though we hope not here to stay. But sex hasn’t changed all that much. Not since the bonobos and silverback gorillas. We use sex for relaxation. We use it for domination, for power, for pride, for pleasure. We use it to titillate, to ejaculate (including women), to cuddle, and to coo.

We even use it to make babies—although we can use in vitro for that too.

We use it to hold back consciousness of mortality, as Jennifer Weiner’s moving story shows. We use it to assert ownership as Daphne Merkin’s story about obsession illustrates. We even use it for love—as Elisa Albert ecstatically shows in “A Fucking Miracle,” and we use it to indulge our kinks—as Linda Gray Sexton shows in exploring asphyxiation. We use it to depict outrageous fantasy—as Marisa Acocella Marchetto demonstrates in her imaginative graphic piece, “Cock of My Dreams.”

In none of this are we radical. Sappho got there first. And so did Catullus, Ovid, and Petronius, Chaucer, Boccaccio, Shakespeare, Henry Miller, Norman Mailer, and so many others.

We have not invented adultery. Nor have we invented kink. We are just the same old primates who have, for thousands of centuries been hallooing at one another from the trees and doing it behind the bushes.

The beat of blood in the slippery clitoris, the thrusting of the cock—none of it surprises. Fay Weldon talks about her first experience of sex and how much she liked it despite her dowdy mother-made cover-up. She wasn’t supposed to like it, but she did anyway. Nature made us that way, and not all the promises of the promise keepers or the purity-ring wearers can change it.

So sex is here to stay—though perhaps not for reproduction—as the prophetic Aldous Huxley predicted.

But we like it. We are made to like it. As long as two halves must come together to make a whole, there is no chance that we will stop clicking the “like” button.

And once women start writing about it, there’s no stopping us.

Doing it

is another thing, apparently.

Rereading these contributions, however, I cannot help thinking that the fantasy of perfect sex is far more powerful than explicit sex itself. There is much yearning here, and the yearning is often more thrilling than the consummation. Sexual women are in touch with their fantasy lives. They do not always have to act out their fantasies. I think the so-called sexual revolution misunderstood the importance of fantasy in our lives. We do not have to make fantasy literal to be enriched by it. Fantasy itself is empowering. Because my contributors span the generations, we read about the great range of sexuality—subtle and overt. Sex has changed a lot, and it hasn’t. Sex is more about imagination than friction. Most of these efforts are psychological rather than explicit.

I chose to have both fiction and nonfiction pieces because the line between the two has blurred in our time and fantasy enriches both genres. Since

Dubliners

and

Ulysses,

memoir and fiction have drifted together—as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Miller both predicted. And our physical lives cannot be separated from our emotional or artistic lives.