Summer of '68: The Season That Changed Baseball--And America--Forever (21 page)

Read Summer of '68: The Season That Changed Baseball--And America--Forever Online

Authors: Tim Wendel

Tags: #History, #20th Century, #Sports & Recreation, #United States, #Sociology of Sports, #Baseball

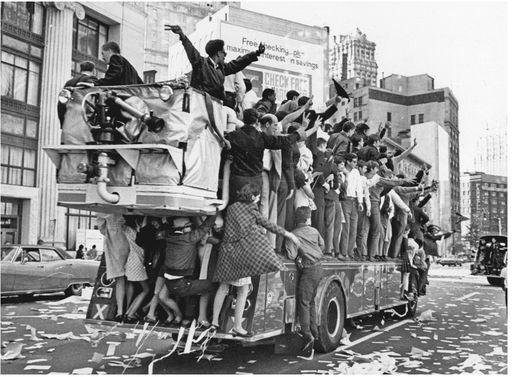

Thanks to complete-game victories by Denny McLain and Mickey Lolich, the Tigers took the final two games in St. Louis to win their first World Series title since 1945. Moments after the final out, the streets of Detroit, where there had been riots only the summer before, filled with fans celebrating their team’s victory for the ages.

Getty Images

PART V

Rewriting the Record Book

Action is character.

—F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

Despite the riots in Chicago, the Democrats moved ahead with their selection of Hubert Humphrey, Lyndon Johnson’s vice president, as their presidential nominee. He would oppose Richard Nixon in the November election, and those new to the game, the ones who had supported Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy, realized that when it came to the Vietnam War, the most divisive issue in the land, little was going to change in terms of public policy.

“After the convention, I was on pins and needles awaiting possible (federal) indictment,” remembered Tom Hayden, one of the Chicago Seven, who was charged with conspiracy and inciting to riot in connection to the Windy City protests. “I thought Humphrey had blown it. Later on, he did break with LBJ when it came to the war and rose in the polls, but it was not enough.”

Hayden grew up in southeastern Michigan, and in fact had played youth ball against several of the 1968 Tigers. Detroit catcher Bill Freehan remembered Hayden as “a little guy, always arguing with the umpires and getting thrown out of games.”

Decades later, Hayden reluctantly agreed with Freehan’s scouting report. “Bill has a good memory,” he said. “We were kids together and we both loved playing ball. I was scrawny, he was a big man. Bill had a great arm, even back then, and he’d sometimes pitch. I managed to get a clutch hit off him once, and made a diving catch in left field on a line drive of his, while he was otherwise mowing us down. Those remain the baseball highlights of my youth.”

In the late fifties and early sixties, before the riots and talk of revolution, the Motor City “played some of the best amateur baseball in America,” Freehan wrote in his memoir,

Behind the Mask

. In high school, when his family moved to St. Petersburg, Florida, Freehan still returned to the Detroit area in the summers, living with his grandparents, so he could play against several of his future Tigers’ teammates and such prospects as Alex Johnson and future basketball star Dave DeBusschere. Willie Horton, who graduated from Northwestern High School in Detroit, believes that’s where the ’68 ballclub really began, where it learned about determination and resiliency—qualities that were about to be tested again.

On August 28, 1968, second baseman Dick McAuliffe returned to the Tigers’ lineup, having served his five-day suspension. Still, the losing streak the team suffered while he was out had taken its toll, and a sense of foreboding had settled in Detroit. The California Angels were coming to town, followed by the hard-charging Baltimore Orioles. It had been the Angels the year before who had eliminated the Tigers on the final day of the season, in that wild dog pile with four teams in contention down the stretch. Now with the ’68 pennant race on the line, they relished the chance to play spoilers once more.

“Wouldn’t it be funny if we did it again?” asked Angels manager Bill Rigney before the start of the two-game set.

In the first game, ace Denny McLain was on the mound for the Tigers, looking to break his two-game losing streak—his longest of the season. Facing off against him was Tom Burgmeier, pitching for the Angels.

From the start, the contest was a heated one, with McAuliffe’s first at-bat returning from suspension nearly echoing the one that sent him there. It appeared Rigney had taken a page from the White Sox’s playbook—Burgmeier came in high and tight, moving the Tigers’ lead-off hitter off the plate. For a moment, McAuliffe glared out at Burgmeier, ready to charge the mound. “It took a lot for me to stop there,” McAuliffe said decades later. “But I knew I couldn’t risk another suspension. Not with the way we were struggling.”

With McAuliffe still in the game, igniting the attack, the Tigers scored three times in the second inning with Freehan cracking a two-run homer. In the eighth inning, Freehan was hit by a pitch for the twenty-second time that season. He stared out at California reliever Bobby Locke as he made his way to first. Later he came around to score on Jim Northrup’s home run.

With the victory, McLain became the first American League pitcher to win twenty-six games since Bob Feller and Hal Newhouser in 1946. Afterward he was asked how he could pitch and somehow win with such a sore shoulder. “Because we were only four games ahead of Baltimore,” he replied.

Back in Baltimore, Frank Howard made the Tigers’ victory especially sweet as his home run propelled the Washington Senators past the Orioles, 3–2. Detroit’s lead was back up to five games.

The next afternoon, Mickey Lolich made his third start since being released from the bullpen. He allowed three Angel hits in the first two frames but then settled down, retiring twenty consecutive batters. Willie Horton supplied the firepower, walloping his thirty-first homer of the year. The blast landed in the center-field stands, the same area where he once delivered a homer at the tender age of sixteen in the Detroit Public School League championships. The Tigers won 2–0, and back in Baltimore the lowly Senators somehow did it again, this time tripping up the Orioles 5–4 in eleven innings.

Always eager to play the prophet, Rigney told the media if Detroit took just one from Baltimore in the upcoming series “it will just about be over.”

The big home stand against Baltimore opened on Friday, August 30, and 53,575 packed Tiger Stadium, the largest crowd since 1961. A highway sign on the Lodge Expressway leading to the ballpark read, GO GET ‘EM TIGERS!!! Detroit right-hander Earl Wilson didn’t disappoint, pitching a four-hitter and driving in four runs with a single and home run.

The Orioles won the next day, 5–1, behind Dave McNally’s pitching gem and Paul Blair’s three-run home run. Afterward Weaver said, “If we beat them tomorrow, the pressure’s back on them.”

Rain delayed the start of the rubber game of the three-game series for forty-five minutes, complicating pregame preparation for McLain, who still nursed a sore shoulder. Unable to get loose, he fell behind 2–0 when the first two Orioles he faced singled and homered.

With that Smith hustled out to the mound and asked McLain if he wanted out. Was the shoulder too painful to continue?

“It’s the first goddamn inning,” McLain replied. “There’s 42,000 people here—it’ll get better.”

Smith looked to Freehan, who had joined the discussion on the mound.

“How ’s he throwing, Billy?” Smith asked.

“How would I know?” the catcher said. “I haven’t caught anything yet.”

That broke the tension and McLain remained in the game.

Northrup tied it with a two-run shot in the bottom of the first inning. But then yet another rain delay exasperated McLain. As the rain fell, he took a hot shower in the home clubhouse, trying to loosen up his aching shoulder. When the clouds lifted, McLain was back on the mound and the Tigers soon pegged him to a 4–2 lead. But the Orioles answered and after a walk, a single, and an RBI by Frank Robinson, trimmed the margin to a single run.

With men on first and second base, with none out, up stepped the Orioles’ Boog Powell, the last guy McLain wanted to face in that situation. “I could never get that son of a bitch out,” McLain recalled. “I hated hitters who hung out over the plate, and Powell was one of those. I’d already tried everything with him. I used to yell to him, ‘Fastball’s coming—I might as well tell you so we can speed up the game.’ And I’d throw him a fastball. Other times, I’d lie and see if that would help, but it never did.”

This time McLain wanted to come inside, but instead the pitch caught too much of the plate. Powell smashed the offering right back at the pitcher. In self-defense, McLain stabbed at it and somehow caught the screaming line drive for the first out.

With that he turned and fired to shortstop Tom Matchick at second base for the second out, and Matchick threw on to first baseman Norm Cash to double off Robinson for the third out. Bing-Bang-Boom. Triple play.

“As was discovered long ago, Denny McLain had this flair for showmanship, this knack of doing things a little differently,” Jerry Green wrote. “ What other ballplayer had met his future wife when his bat flew into the grandstands at a kids’ game and struck her? Who else in the big leagues played the organ?”

And who else but Denny McLain could escape trouble by starting a triple play?

“The ball was heading right at my head,” he said. “If I hadn’t caught it, it would’ve killed me.”

No matter that the ball was actually headed for his midsection. Why let the truth get in the way of a good story, right? From there, McLain cruised, striking out nine and raising his record to 27–5. Afterward, the winning pitcher announced with confidence, “I think the pennant race is getting near over.”

Can a guy stuff too much good fortune into a single season? Can somebody’s good luck be so bright and beguiling before one starts to wonder when the proverbial piper will need to be paid? While McLain’s teammates were beginning to wonder, meanwhile the winningest pitcher since Dizzy Dean thirty-four years before continued racing full-bore toward the horizon.

After the Orioles series, the Tigers traveled to the West Coast, where their ace ushered Ed Sullivan and singer Glen Campbell around the Detroit clubhouse, introducing them to his teammates. While his fellow Tigers were shy or even envious, McLain reveled in the attention. It was all good, he told anybody who would listen, as if he were convincing himself. Even a piece in

Life

magazine hinting that he might be too distracted in flying and his music for his own good didn’t upset McLain that much. The talkative right-hander remained eager to embrace the moment.

Soon afterward McLain was scheduled to go for his thirtieth victory on a Saturday—September 14, 1968—against the Oakland Athletics. The night before the game Sandy Koufax and Dizzy Dean visited the ballpark. Koufax was a member of the NBC television crew in town to nationally broadcast Saturday’s game. Dean, meanwhile, had traveled from his home in Wiggins, Mississippi, to bear witness to the thirty-victory torch being passed. “I’m getting more publicity now with Denny winning thirty than I did when I won thirty,” Dean said.

Years later, McLain remembered Koufax as a class act, while Dean “was just a good ole boy who wanted to talk about the football season and point spreads.”

Unable to resist a dig at his larger-than-life teammate, Lolich put up a sign on the pillar in the middle of the home clubhouse. “Attention Sportswriters,” it read, “Denny McLain’s Locker This Way,” with big arrow pointing stage right. In perhaps the most intriguing interview conducted that season, he spoke with the

Detroit News

as the media hordes swirled about McLain.

“How could I be a thirty-game winner?” Lolich asked. “How could I ride my motorcycle on the

Ed Sullivan Show

?”

Lolich explained that he was getting into music, too, learning to play the drums. But in a stream-of-consciousness ramble, Lolich honestly summed up what it was like to live in McLain’s large shadow that season. “If I have a good year next year and win twenty, they’ll say, ‘So what?’”

Looking back over at McLain and all of the attention that enveloped him, Lolich added, “He’s sort of ruined things for everybody around here.”

After such a buildup, McLain’s thirtieth could have been anticlimatic. Instead it was again the kind of thriller that had become so indicative of the Tigers’ remarkable season.

By this point in the season, the game really didn’t have any pennant implications as the Tigers were only days away from clinching. The Orioles were history, reconciled with positioning themselves to win it all the following season. Yet on that sunny afternoon in Detroit, 33,688 fans still jammed into the old ballpark at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull. McLain’s opposing number was Oakland’s Chuck Dobson and before the game Jim Pagliaroni, the Athletics’ backup catcher—the one who had caught Catfish Hunter’s perfect game—did up a sign of his own that read “Dobson goes for #12 today.”

Usually pitchers don’t talk to the press before a start. Yet when McLain saw the crowd around his locker, no one was very surprised when he found he had plenty to say. “I never understood how a writer could have anything to do with my performance,” he later explained. “What a special day it was and what an absolutely marvelous time to be alive. I loved it all. I was a circus leader and these were my animals following me around. I told the writers that I’d been on the phone until midnight. Logically, one of them asked me what I’d dreamt. I said, ‘I dreamt about losing my contact lenses, and I spend more on contact lenses than most guys make.’”