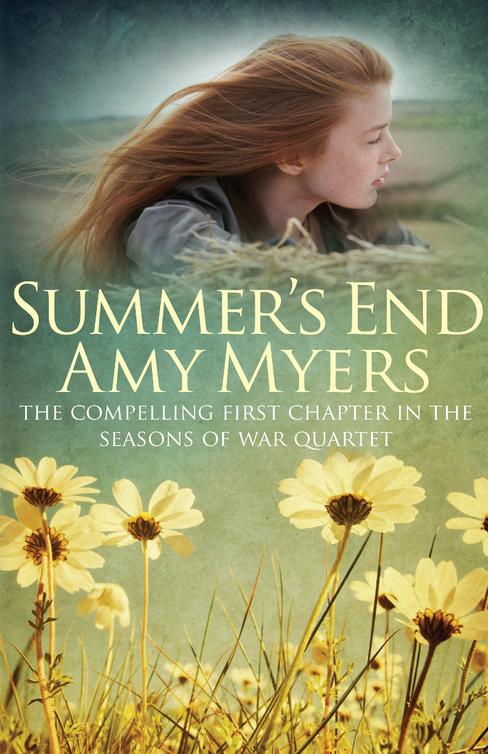

Summer's End

Authors: Amy Myers

Amy Myers

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

For

Audrey

with

gratitude

and

love

My

thanks

are

due

above

all

to

my

editor

Jane

Wood

of

Orion

from

whom

the

idea

for

this

book

stemmed,

and

to

both

her

and

my

agent,

Dorothy

Lumley

of

the

Dorian

Literary

Agency,

for

their

continuous

encouragement.

In

addition,

I

have

prized

the

help

that I

have

received

from

Alan

Bignell,

Ned

Binks,

The

Church

of

England

Record

Centre,

my

uncle

Albert

Hudson,

Martin

Kender,

Audrey

Kimber,

Mary

Lewis

and

Sheelagh

Taylor.

To

all

of

them

my

deep

gratitude.

âT

om, Tom, the Piper's son â¦'

The Austin's engine chugged rather than sang as it tackled the shallow incline past Tillow Hill, a cloud of dust billowing behind to mark its passage. Always the son, never the daughter, Tilly thought bitterly.

âStole the pig and away she run â¦'

Run? She'd

marched

out. Families should shelter, not judge, surely? There'd been no haven for wounded chicks at

her

home, though â not unless she betrayed everything she believed in. Yet what, ironically, was she doing now? Why, motoring straight towards another family, her brother Laurence's. Life at the Rectory was different, however, Ashden was different, and they sang to her a siren song.

âOver the hills and far away â¦' In the mildness of the Sussex air, it would be all too easy to abandon the fight, and let England drowse on. But she couldn't, and some day soon she would be forced to leave even Ashden.

As the Austin motored over the brow of the hill, she glimpsed Lovel's Mill and now the first tentative leaves of Gowks Wood, the cuckoos' wood. It was early April and Ashden's children would be listening eagerly for the sound of the first cuckoo, just as Laurence's brood used to when they were younger. Caroline her favourite, Isabel, Felicia, Phoebe and nephew George. Well, my pretty darlings, here comes your cuckoo! Tilly laughed, but soon stopped, for it hurt to do so, and, besides, there was no humour left in her.

She turned the wheel of the tourer to round the bend, and the wind caught her face, attacking even the secure moorings of her black toque, and assailing her dustcoat. It exhilarated her. Something was thudding as loud as the engine, her heart perhaps, if she still had one. Then the wind was breeze, and before her was the rose-red warmth of Ashden.

From Stumbly Bottom, wild daffodils and primroses sang of spring, trumpeting her arrival, but the woman did not need trumpets.

Already, perhaps, she had been over-daring, by choosing to drive here by motor-car. Call it her gesture, her snook at disapproving Society. Ashden, she thought with a touch of impatience, could call it anything it dashed well chose. She had promised her brother to abide by Ashden's rules while she was here, both in the Rectory and in the village, and that meant slipping back into the role she had filled at home â no, not home any more, at Dover: dutiful, all fires damped down, and waiting.

Such had been the pace of events in her life recently, however, that it was nearly two years since her last visit to Ashden, and the village unfolded itself in one panoramic swoop as memory's clutch released its hold. Bankside, rising from the Withyham road to red-brick cottages, the ugly Village Institute, the proudly white Norville Arms, and beyond it Nanny Oates' cottage. She must go to see Nanny tomorrow; she'd be expected of course, Tilly realised with pleasure. Over to the left was St Nicholas, Laurence's church, and beyond it the village high street. Wasn't that a new sign? Teas! Who for, she wondered. Outside boys were playing, spilling all over the roadway. Marbles? Of course, in readiness for the great Marble Day of Good Friday in a few days' time. A girl was bowling a hoop, pinafore skirts flying. Wryly, Tilly noted that she, who believed so fiercely that England needed change, was already being seduced by a scene that was yesterday, today â and, if she knew Ashden, had every intention of being tomorrow.

People were looking up. Surely now, in 1914, motor-cars were not so unusual even on this remote Sussex road? Motor-cars were the future, however, even Ashden must see that. She was glad that in a spirit of bravado she had kept the top down, for this, the Austin's first outing since its winter lay-up.

Taking a deep breath, she gripped the wheel to turn in to the familiar driveway. Who would come racing out to greet her? Anyone? She gave a defiant toot on the hooter as she swept around the garden, its grass still sheltering the countless daffodils and tiny blue scillas that dotted it in clumps under the trees.

Somewhere a dog barked, her tyres crunched on the gravel, still muddy from the March rain. Loving mud they called it in Sussex, because it held so fast to you. Like Sussex itself in the mind and in the heart. Somewhere a door slammed, girls' voices were raised in laughter, sounds distanced by her own memories. She had driven over

the hills and far away, and now âfar away' was

here.

The smell of the rich earth brought out by the spring sun caught her with a rush of emotion for the timeless England she both loved and resented. The late afternoon sun mellowed the red brick of the rambling Rectory, and the front door was opening.

T

he Rectory shook itself awake. Outside the red bricks were already brightening in the early morning light. Inside, still dark, the house waited expectantly as the first feet clattered down the servants' stairs. Soon the shutters would be flung open, letting the new day into the Rectory's cheerfully cluttered rooms. In the kitchen a print-gowned backside swayed vigorously as its owner attacked the kitchen-range with black-lead, and another was soon at work in the dining room with cinder pail, black-lead, broom, and tea-leaves to strew on the carpet for easier sweeping. Any moment now the descent of a superior being would herald the turning of the key in the clock of the Rectory's daily life: the cook-housekeeper Mrs Dibble was never late.

Upstairs in her small room on the second floor Agnes Pilbeam yawned. It was six o'clock and it was her privilege as parlourmaid to enjoy another thirty minutes in bed. She was no longer a mere housemaid like that dratted Harriet, but almost old Dribble Dibble's equal. Any moment now, Mrs Dibble would, she guessed, be strutting round âher' kitchen, superintending Myrtle, the new tweeny, like a sergeant-major as she prepared breakfast for the servants and later for the family. She debated whether the moral advantage of keeping even with Mrs D. by forgoing her precious lie-in was worth it, and decided it wasn't â especially on Easter Day. High up in her small room on the second floor, she felt as far away from grates and bedmaking as the birds singing their spring song in the waving branches of the tall larch tree outside her window. They must think a good day lay ahead â and they were right. It was her half day off.

âWater, Miss Pilbeam.'

The raucous shout was unnecessary. The thump outside the door would have told her that Myrtle had plonked down her jug of hot water. Agnes sighed, forced to contemplate the tasks ahead before she met her Jamie this afternoon. Dribble Dibble was all too adept at nabbing the tweeny during the times when she should properly be

assigned to house cleaning. Not if Agnes Pilbeam had anything to do with it she wouldn't. With sudden resolution she swung her feet to the floor on to the old Wilton carpet â it was threadbare, but nevertheless

carpet

, which was more than Rosie Trott got at the Manor. That reminded her what was unusual about today. Those Swinford-Brownes were coming to luncheon, instead of the Squire. Yet the Hunney family

always

came to the Rectory on Easter Day. She supposed it would not affect her, except in so far as everything that went on in the Rectory mattered to her; it almost intoxicated her, in fact, and had right from the moment she'd nervously asked Mrs Lilley what her wages might be.

âTuppence a week and jam every other day,' had been the alarming answer. It had been Miss Caroline who had explained it was just a joke, a quotation from some book, and the wages were sixteen pounds a year. Then she'd lent her the book, not even asking if she could read. From then on, she felt part of the family. She never let it show, but within herself, she laughed when they laughed, grieved when they grieved and stomped around bad-humouredly when there was stormy weather. And that was inevitable from time to time, what with the Rector and Mrs Lilley, the four girls, young Master George, and now Miss Tilly, the Rector's sister, come to stay.

Often Agnes played silent umpire when these thunderclouds appeared: âMiss Isabel, you're being downright bossy'; âMiss Caroline, don't you let your ma leave everything to you'; âMiss Felicia, stand up for yourself'; âMiss Phoebe, remember you're a young lady now'; âMr George, don't you cheek your father'; and above all, âMrs Lilley, don't let them get away with it!' â by them she meant old Dibble, Percy Dibble, and that Harriet (Agnes's own thorn in the flesh), as well as Mrs Lilley's family.

Or did Mrs Lilley let them get away with it? Agnes reconsidered this as she hopped on one foot struggling with a recalcitrant black stocking. Now she came to think of it, no one did get away with much in the Rectory. For all Mrs L. never seemed to get involved in quarrels, either in her family or in the servants' hall (and what a silly name that was for the converted apple storeroom allotted to them at the back of the house, comfy though it was), everything usually turned out the way Mrs Lilley wanted. Luck, Agnes supposed vaguely.

The Rectory was large; even with seven family, plus six live-in staff (if you could call poor Fred Dibble staff), they rattled around like old

peas in a pod. Somehow, however, the only time it

seemed

large was when the girls and Master George went to Dover once a year to visit the Reverend's mother, the Countess of Buckford. Then she missed the laughs, the cries of horror or disgust, the constant noise. To Agnes, the only child of elderly parents, coming to the Rectory (even though that had meant only a half mile walk down Silly Lane from the cottage she'd lived in with her parents) was like being thrust into a pen at market, deafened by moo's and baa's. She wasn't sure she liked it at first, but once she got used to it, it made her feel safe. And

that

made her think of Jamie again â his warm arms round her and the way it made her feel.

âAgnes Pilbeam, you should be ashamed of yourself,' she informed her reflection in the oval mirror, before slipping her blue print gown over her head, automatically tugging at those dratted garment shields. No afternoon black for her today, she rejoiced. She'd be wearing her Sunday best, her new pink linen costume with a wrap-over skirt, not to mention underneath. Daringly she was going to wear the nainsook camisole and knickers she'd bought in Weekes' in Tunbridge Wells. Her mother would be shocked; if she had her way her daughter would be in cotton bloomers and neck-to-knee whalebone for the rest of her life. But times were changing â because of Jamie Thorn. She'd never let him see how she felt about him, of course; that wouldn't be proper. Any more than she'd let the family see how much being at the Rectory meant to her. It was better that way. She remembered hearing years ago: âThe Royal Sussex is going away, Leaving the girls in the family way.' What did it mean, she asked her mother, only to receive the sharp reply, âIt means keeping yourself to yourself, gal.'

So she had.

Talking of families, she remembered she'd promised to clean Miss Caroline's blue felt hat, the one messed by the jackdaw last week. Miss Caroline had joked that the feather must have annoyed the bird on behalf of his fellows, and made her smile. Strictly speaking, it was Harriet's job as housemaid, but Agnes was known to have a way with stains. Anyway, it was always a pleasure to do something for Miss Caroline. Secretly, she was her favourite â perhaps it was because of her brown curls, and her quick, light way of moving, so different to Agnes's own dull straight lumps of hair, and deliberate steps. She twisted the offending locks up into the usual bun, glad she'd given

them a rosemary rinse when she washed them. Jamie seemed to like her hair, she couldn't think why. She'd do that old hat straight away to be ready for church. For her, Miss Caroline was the centre of the Rectory whirlpool, and if a mix of lime and pearl-ash could help her, then Agnes was only too willing to dab it on.

âCaroline!'

The door of her room crashed open, and defensively Caroline burrowed down under the bedclothes. Pointless, of course, since if Isabel had a crisis she would rampage through the household until it was solved. Why pick on her first, though, on Easter Day of all times? She peered out cautiously to see Isabel posed behind her bedroom door, a Second Mrs Tanqueray, tragedy writ large on her face. Unfortunately her fair curls and English rose complexion, plus her carelessly tied dressing gown revealing dancing corset, bodice and pink tango knickers, made this a difficult role to sustain.

âDespair!' Isabel continued.

âDon't tell me,' Caroline muttered. âYou've torn a button off your glove.'

âWorse. Truly. I've lost my silver buckle.'

âBut that was Grandma Overton's.' In her shock Caroline sat bolt upright.

âI know. Isn't it a nuisance?' Isabel sighed. âBut you do see I simply must have a special buckle. Could I borrow the jet?'

âWhy

must

you?'

âI simply must, that's all. I want to look my best. You do see?' She opened grey-blue eyes earnestly.

âJust because the Swinford-Brownes are coming to luncheon, I suppose?' Caroline came back to the heart of the grievance. It was Easter Day, and for some unknown reason for luncheon this year the Hunneys had been superseded by the ghastly Swinford-Brownes.

The Rectory living was in the gift of Sir John Hunney as lord of Ashden Manor, although neighbouring parishes were held direct in the Diocese of Chichester, so surely this meant that close links should be maintained between the two houses? Caroline had always thought of Ashden Manor as a second home, since she and Isabel had shared a governess with the three children of the Manor, Reginald, Daniel and Eleanor. Felicia, Phoebe and George, being younger, had been drawn into the family by a kind of osmosis.

So why was everything to be different today? George was furious because Reggie and Daniel provided a rare ration of menfolk among the monstrous regiment of women he lived with and Felicia upset because she, as Caroline, liked tradition. Only Phoebe was not too perturbed, probably because she could poke fun at some new victims, her sister thought indulgently.

Caroline realised that Isabel was getting her own way as usual over the jet, but, if she refused to produce it, the large eyes would fill with unshed tears and Isabel would depart in silent bravery to tell Mother all about it. As usual, her sense of proportion came to her aid.

âAll right. But be

careful

.' Despite her porcelain looks, Isabel was renowned for her clumsiness, and jet was fragile.

Isabel jumped up and planted a kiss on her sister's forehead. âYou're a dear. I knew you would.' She skipped over to the dressing table, yanked open the lid of the wooden jewellery box (Caroline's own remembrance of Grandma Overton) and extracted her prize.

Caroline watched her sister prance out. Only Isabel, she thought in amusement, would have bothered to tack lace all the way round cheap cotton knickers. There were four years between herself and Isabel since sister Millicent, born in 1890, had died of diphtheria at a year old. Once upon a time she had looked up to her pretty, talented elder sister in blind adoration. At sixteen Isabel had gone to Paris to finishing school, paid for by Grandmother, Father's dragon of a mother, the Dowager Countess of Buckford. After her return, Caroline had seen her with a new detachment, and adoration had tempered into affectionate tolerance. Somehow for all Isabel's looks and charm she was still unwed at twenty-five, and Caroline suspected the fact terrified her. Isabel, of all of them, found the constant lack of money at the Rectory hardest to treat as a challenge, as Mother encouraged them to do.

She decided she could no longer ignore the rapidly cooling water Myrtle had brought in twenty minutes ago, and reluctantly put foot to floor.

The Rectory boasted two bathrooms, one for themselves and one for the servants, but seven of them, let alone any guests, all expecting to wash at the same time led to strike action by both ancient boiler and boiler guardian, Percy Dibble. Since Father's timetable necessarily governed the Rectory, he had precedence, with Mother coming

second, and, then, of course, came Isabel. Somehow no one ever challenged her right.

âBlackbird has spoken'. Caroline thrust up the sash in her everyday ritual. Below her lay the Rectory gardens and beyond several farms, and beyond them the Forest of Ashdown, that mysterious and enchanted âother place', almost all that was left of the great prehistoric forest of Anderida which had once covered three counties and even now cast its spell of the past on those who stood still to receive it. âMy sermon today is life,' Caroline solemnly informed the world. âHe that hath ears to hear let him hear.' A blackbird in the larch tree apparently didn't, because he promptly flew away with a loud cry of alarm, followed by annoyed clucks. This was her life, these green lawns, this village, this church, this house, and every day she reminded herself how much she loved it, in case, she supposed, something changed. As it might do. Perhaps there was still time to be an intrepid lady traveller, another Lady Hester Stanhope or Isabella Bird; maybe she'd travel the desert like Gertrude Bell and write a book as good as

The Desert and the Sown.

Now the water really was cold. Ugh! She hurried over her ablutions, impatient now for the day to get going as she struggled into corset and stockings. She had already put on her new straight-skirted costume when she remembered she was going for a walk with Reggie Hunney this afternoon.

Some

consolation for the coming disaster of luncheon. Still, she couldn't wear her blue walking skirt for church and anyway she'd forgotten to ask Harriet to clean the bottom from last week's mud splashes. She thought enviously of the frightful Patricia Swinford-Browne and her daring appearance in old-fashioned bloomers on her bicycle. A brief appearance, for Patricia's mother had all but fainted. All the same, trousers, or at least divided skirts, were entirely sensible forms of dress. She regarded herself critically in the mirror, thankful that for once her wayward hair had condescended to be swept up reasonably neatly and to remain there shackled firmly with pins. Perhaps the day wouldn't be so bad after all. She raced down the stairs to family prayers and breakfast. Dear Aunt Tilly, still not recovered from the nose and throat problems that had brought her here a few days to convalesce, would be deputising for Father and Mother who were still at early Easter Celebration. Tilly was next in seniority, but it was hardly fair on her, Caroline thought. There was something a little odd about this visit, for her aunt was very vague

about how long she intended to stay. She could not, Caroline wondered, by any chance have quarrelled with Grandmother? No, surely not; she was far too quiet and unassuming to quarrel with anybody.