Surfing the Gnarl (7 page)

Authors: Rudy Rucker

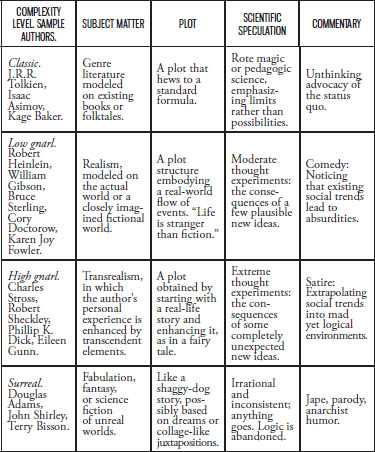

In any case, if you disagree with my classifications, so much the betterâmy main goal is to offer a tool for thought. In the four sections to come, I'll say a bit about the thinking that went into my table's four right-hand columns.

Regarding the kinds of characters and situations that one can write about, my sense is that we have a fourfold spectrum of possible modes: simple genre writing with stock characters, mimetic realism, the heightened kind of realism that I call transrealism, and full-on fabulation. Both realism and transrealism lie in the gnarly zone. Speaking specifically in terms of subject matter, I'd be inclined to say that transrealism is gnarlier, as it allows for more possibilities.

What do I mean by transrealism? Early in my writing career, my friend Gregory Gibson advised, “It would be great to write science fiction and have it be about your everyday life.” I took that to heart. The science fiction novels of Philip K. Dick were an inspiration on this front as well.

In 1983, having read a remark where the writer Norman Spinrad referred to Dick's novel

A Scanner Darkly

as “transcendental autobiography, “ I came up with the term

transrealism,

to represent a synthesis between fantastic fabulation (trans) and closely observed character-driven fiction (realism), and I began advocating a transrealist method of writing.

- Trans.

Use the SF and fantasy tropes to express deep psychic archetypes. Put in science-fictional events or technologies which reflect deeper aspects of people and society. Manipulate subtext. - Realism.

Possibly include a main character similar to yourself and, in any case, base your characters on real people you know, or on combinations of them.

Twenty novels later, I no longer feel I have to go whole hog with transrealism and cast my friends and family into my books. I think they got a little tired of it. For awhile there, I was like Ingmar Bergman, continually making movies with the same little troupe of actors/family/friends. These days I'm more likely to collage together a variety of observed traits to make my characters, like a magpie gathering up bright scraps for a nest.

I've come to think that you can in fact write transreally without overtly using your own life or specific people that you know. Even without having any characters who are particularly like myself, I can write closely observed works about my own life experiences. And if I'm transmuting these experiences with the alchemy of science fiction, the result is transreal. So I might restate the principles of transrealism like this.

- Trans.

The author raises the action to a higher level by infusing magic or weird science, choosing tropes so as to intensify and augment some artistically chosen aspects of reality. Trans might variously stand for transfigurative, transformative, transcendental, transgressive, or transsexual. - Realism.

The author uses real-world ideas, emotions, perceptions that he or she has personally experienced or witnessed.

In the table's next column, I present a fourfold range of plot structures. At the low end of complexity,

we have standardized plots, at the high end, we have no large-scale plot at all, and in between we have the gnarly somewhat unpredictable plots. These can be found in two kinds of ways, either by mimicking reality precisely, or by amplifying reality with incursions of psychically meaningful events.

A characteristic feature of any complex process is that you can't look at what's going on today and immediately deduce what will be happening in a few weeks. It's necessary to have the world run step-by-step through the intervening ticks of time. Gnarly computations are unpredictable; they don't allow for short-cuts. Thus, as I mentioned before, the last chapter of a novel with a gnarly plot will be, even in principle, unpredictable from the contents of the first chapter.

Although I believe this, over the years I've come to feel that it's not a bad idea to maintain an outline, however inaccurate. The detailed eddies of the story's flow will indeed have to work themselves out during the writing, but there's no harm in having some sluices and gutters to guide the narrative process along a harmonious and satisfying course.

I've learned that if I start writing a novel with no plot outline at all, two things happen. First of all, the readers can tell. Some will be charmed by the spontaneity, but some will complain that the book feels improvised, like a shaggy-dog story. Second, if I'm working without a plot outline, I'm going to experience some really painful and anxious days when everything seems broken, and I have no idea how to proceed. My mentor Robert Sheckley referred to these periods in the compositional process as “black points.”

These days, writing an outline makes writing a novel easier on me. Perhaps it's a matter of mature craftsmanship versus youthful passion. Or maybe I'm just getting old. I've developed a fairly elaborate process. Even before I start writing a new book, I create an accompanying notes document in which I accumulate outlines, scene sketches and the like. The notes documents end up being very nearly as long as my books, and when the book comes out, I usually post the corresponding notes document online for perusal by those few who are very particularly interested in that book or in my working methods. (Links to these notes documents and some of my essays on writing can be found at

www.rudyrucker.com/writing

.)

It goes almost without saying that my outlines change as I work. Things emerge. It's like life! After writing any scene in a given chapter, I find that I have to go back and revise my prior outline of the following scenes.

In the end, only the novel itself is the perfect outline of the novel. Only the territory itself can be the perfect map. In this connection, I think of Jorge Luis Borges's one-paragraph fiction, “On Exactitude in Science,” that contains this sentence: “In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers' Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it.”

(CollectedFictions,

225).

Outline or not, the only way to discover the ending of a truly living book is to set yourself in motion and think constantly about the novel for months or years, writing all the while. The characters and gimmicks and social situations bounce off each other like eddies in a turbulent wakes, like gliders in a cellular automaton simulation, like

vines twisting around each other in a jungle. And only time and extensive mental computation will tell you how the story ends. As I keep stressing, gnarly processes have no perfectly predictive short-cuts.

What stampedes are to westerns or murders are to mysteries,

power chords

are to science fiction. I'm talking about certain classic tropes that have the visceral punch of heavy musical riffs: blaster guns, spaceships, time machines, aliens, telepathy, flying saucers, warped space, faster-than-light travel, immersive virtual reality, clones, robots, teleportation, alien-controlled pod people, endless shrinking, the shattering of planet Earth, intelligent goo, antigravity, starships, ecodisaster, pleasure-center zappers, alternate universes, nanomachines, mind viruses, higher dimensions, a cosmic computation that generates our reality, and, of course, the attack of the giant ants.

When a writer uses an SF power chord, there is an implicit understanding with the informed readers that this is indeed familiar ground. And it's expected the writer will do something fresh with the trope. “Make it new,” as Ezra Pound said, several years before he went crazy.

Mainstream writers who dip a toe into what they daintily call “speculative fiction” tend not be aware of just how familiar are the chords they strum. And the mainstream critics are unlikely to call their cronies to task over failing to create original SF. They don't have a clue either. And we lowly science-fiction people are expected to be grateful when a mainstream writer stoops to filch a bespattered icon from our filthy wattle huts? Oh, wait, do I sound bitter?

When I use a power chord, I might place it into an unfamiliar context, perhaps describing it more intensely than usual, or perhaps using it for a novel thought experiment. I like it when my material takes on a life of its own. This leads to the gnarly zone. As with plot, it's a matter of working out unpredictable consequences of simple-seeming assumptions.

The reason why fictional thought experiments are so powerful is that, in practice, it's intractably difficult to visualize the side effects of new technological developments. Only if you place the new tech into a fleshed-out fictional world and simulate the effects on reality can you get a clear image of what might happen.

In order to tease out the subtler consequences of current trends, a complex fictional simulation is necessary; inspired narration is a more powerful tool than logical analysis. If I want to imagine, for instance, what our world would be like if ordinary objects like chairs or shoes were conscious, then the best way to make progress is to fictionally simulate a person discovering this.

The kinds of thought experiments I enjoy are different in intent and in execution from merely futurological investigations. My primary goal is not to make useful predictions that businessmen can use. I'm more interested in exploring the human condition, with literary power chord standing in for archetypal psychic forces.

Where to find material for our thought experiments? You don't have to be a scientist. As Kurt Vonnegut used to remark, most science fiction writers don't know much about science. But SF writers have an ability to pick out some odd new notion and set up a thought experiment. As Robert Sheckley remarked to me when he was

living in a camper in my driveway, “At the heart of it all is a rage to extrapolate. Excuse me, shall I extrapolate that for you? Won't take a jiffy.”

The most entertaining fantasy and SF writers have a rage to extrapolate; a zest for seeking the gnarl.

I'm always uncomfortable when I'm described as a science-fiction humorist. I'm not trying to be funny in my work. It's just that things often happen to come out as amusing when I tell them the way I see them.

Wit involves describing the world as it actually is. And you experience a release of tension when the elephant in the living room is finally named. Wit is a critical-satirical process that can be more serious than the “humorous” label suggests.

The least-aware kinds of literature take society entirely at face value, numbly acquiescing in the myths and mores laid down by the powerful. These forms are dead, too cold.

At the other extreme, we have the chaotic forms of social commentary where everything under the sun becomes questionable and a subject for mockery. If everything's a joke, then nothing matters. This said, laughing like a crazy hyena can be fun.

In the gnarly zone, we have fiction that extrapolates social conventions to the point where the inherent contradictions become overt enough to provoke the shock of recognition and the concomitant release of laughter. At the low end of this gnarly zone we have observational commentary on the order of stand-up comedy. And at the higher end we get inspired satire.

In this vein, Sheckley wrote the following in his “Amsterdam Diary” in

Semiotext[e] SF

(Autonomedia, 1997):

Good fiction is never preachy. It tells its truth only by inference and analogy. It uses the specific detail as its building block rather than the vague generalization. In my case it's usually humorousâno mistaking my stufF for the Platform Talk of the 6th Patriarch. But I do not try to be funny, I merely write as I writeâ¦. In the meantime I trust the voice I can never loseâmy own ⦠enjoying writing my story rather than looking forward to its completion.

I have a genetic predisposition for dialectic thinking. We can parse cyberpunk as a synthesizing form.

- Cyber.

Discuss the ongoing global merger between humans and machines. - Punk.

Have the people be fully nonrobotic; have them be interested in sex, drugs, and rock ân' roll. While you're at it, make the robots funky as well! Get in there and spray graffiti all over the corporate future.

As well as amping up the gnarliness, cyberpunk is concerned with the maintaining a high level of information in a storyâwhere I'm using “information” in the technical computer-science sense of measuring how concise and nonredundant a message might be.

By way of having a high level of information, it's typical for cyberpunk novels to be written in a somewhat

minimalist style, spewing out a rapid stream of characterization, ornamentation, plot twists, tech notions, and laconic dialog. The tendency is perhaps a bit similar to the way that punk rock arose as a reaction to arena rock, preferring a stripped-down style that was, in some ways, closer to the genre's roots.