Surveillance or Security?: The Risks Posed by New Wiretapping Technologies (35 page)

Read Surveillance or Security?: The Risks Posed by New Wiretapping Technologies Online

Authors: Susan Landau

A roaming cell phone sends a signal to the HLR once it is turned on

and periodically after that. Since calls to the phone naturally go through

the Mobile Switching Center (MSC) while routed to the roaming phone's

cell, the tap can be turned on at the MSC. Tapping outgoing calls is different. Once the roaming cell phone "registers" with the home switch,

outgoing calls made from the phone do not consult the HLR, and thus do

not necessarily activate the wiretap. There are ways to circumvent this

problem (including routing the call to the target's home system and back

again), but doing so may cause the cell phone to behave anomalously. This

could alert a suspicious target. If that aspect of cell phones is a problem in

investigations, society's ubiquitous use of mobile phones has given law

enforcement more than it has taken away. Recall, for example, the criminal

investigator who noted that phone records give the same information as

thirty days of covering a suspect with a five-person surveillance team. The

massive amount of transactional information available has greatly simplified law enforcement's work. Criminals now advertise both their whereabouts and their network of associates.

Voice over IP is a different matter for law enforcement wiretapping.4o

Some forms of VoIP present no particular challenge for legally authorized

wiretaps. Intercepting a VoIP call made from a fixed location with a fixed

Internet address that connects directly to a large ISP's switch41 (e.g., a home

computer with a direct network connection) is the equivalent of tapping

a normal phone call, and presents no technical problems. The VoIP call

connects to the PSTN at a predetermined gateway switch; the wiretap is

placed at that switch. If the call is peer-to-peer VoIP, however, establishing

the wiretap is significantly more complicated. To understand why, we need

to consider how the VoIP connection is established.

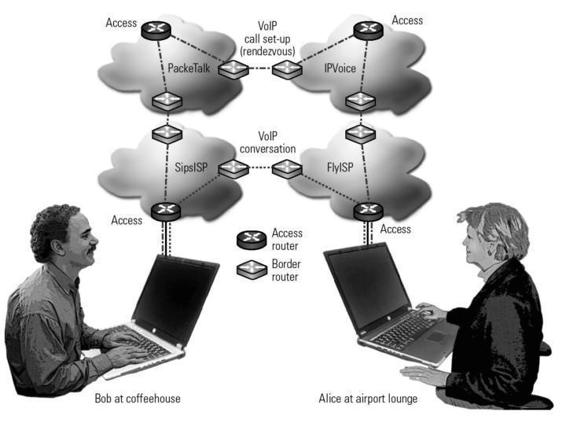

Suppose VoIP subscriber Alice wants to make a VoIP call to Bob. As in

figure 8.1, Alice is in an airport lounge and has Internet service through a

local provider, F1yISP. Alice starts up a VoIP session and types in Bob's

identifier, [email protected]. F1yISP connects to Alice's VoIP service provider, IPVoice, which starts a call setup process with Bob's VoIP service

provider, PackeTalk. PackeTalk checks whether Bob is online. If so, PackeTalk passes on Bob's current IP address, obtained from his local ISP,

SipsISP, to IPVoice, Alice's VoIP service provider. This is the VoIP call setup

step, or rendezvous. IPVoice passes Bob's current IP address to F1yISP, Alice's

local ISP, and PackeTalk passes Alice's current IP address to SipsISP. Then

the two VoIP service providers, PackeTalk and IPVoice, exit the picture.

The problem for law enforcement is the wiretap location; the VoIP communication, which is just a data connection, travels peer to peer through the Internet "cloud." One could have the VoIP provider guide the target

to a rendezvous point controlled by law enforcement and a tap could be

installed there. This solution, however, does not solve the problem of

wiretapping highly mobile, widely traveling communicators, whether road

warriors, drug dealers, terrorists, or spies engaged in their tradecraft.

Figure 8.1

Telecommunication flows. Illustration by Nancy Snyder.

Consider the scenario in which law enforcement has a court order to

wiretap Alice's calls. A wiretap can readily be installed at Alice VoIP service

provider. Alice's VoIP calls are unlikely to traverse this router. Instead the

wiretap should be installed at F1yISP, the Internet analogy of the telephone

central office. But how does law enforcement do this in real time to capture

Alice's calls to Bob? Unless law enforcement shares the wiretap order with

all possible Internet service providers-clearly not viable-the local ISP is

unlikely to be aware of Alice's wiretap order in advance. In order for the

tap to work, the local access routers need instructions from Alice's VoIP

provider to wiretap her-and these instructions need to arrive and be

implemented instantaneously.

The complexity of the situation is clear. Alice's VoIP service provider

may be anywhere on the network. It may or may not have a relationship

with the ISP that is providing Alice with local service. (If Alice's VoIP provider were owned by her ISP-or vice versa-the situation would be simpler,

but there is no reason to expect this.) The order must be responded to

without necessarily having sufficient time to determine its legitimacy.

Much of the time when a wiretap order arrives at the central office, the

paperwork arrives sometime after the law enforcement official has asked

the phone company technicians to start the tap, an arrangement that

works because law enforcement and the phone company technicians know

each other (a variant on all wiretapping is local). For VoIP wiretapping to

succeed, the wiretapping order will be at one location, but the actual wiretapping must be done somewhere else completely.

A further complicating factor is that like many Internet communications and unlike the PSTN, VoIP is identity agile, with users easily able to

have multiple identities: Bob_in_Paris_Apri109, Bob_in_Madrid_Apri109,

Bob_in_Vancouver_May09. To track Bob, the first issue is to recognize that

these multiple identities are a single user, and this is difficult unless one

has access to content and not just call-identifying information.

The installation of a wiretap at Alice's current ISP raises issues of trust.

How can Alice's local ISP know that the wiretap request is legitimate? The

order will be authenticated, but that is not sufficient. Furthermore, how

can law enforcement trust the local ISP to properly wiretap Alice (and not,

for example, tip off Alice that her communications are being surveilled)?

The request to wiretap can cross borders and this complicates matters even

more. Alice and Bob might be in the United States but using a VoIP provider elsewhere. Or Alice might be anywhere in the world but using a

U.S.-based VoIP provider.

For wiretapping to work in such a dynamic system, not only must wiretapping software be available at all ISPs, it must be real-time configurable.

As the example from Vodafone Greece demonstrates, the ability to do so

remotely and on the fly creates security risks.

Consider what needs to be done to secure the wiretapping facility. That

involves securing the physical setup of the switching and routing equipment-and how plausible a scenario is this when the ISP is the local coffee

shop or a free wireless network in a town or neighborhood?-and securing

the logic of the switches and routers. As of late 2009, the United States

had almost 1,500 domestic ISPs with fewer than 100 employees. These are

highly unlikely to have the expertise to secure wiretapping configurations,

or even adequate physical security to prevent tampering.

PSTN wiretapping is built on the model that the wiretap can be placed

on the line to the user's house or at the telephone company central office

to which the user connects. But Internet users have no such facility. Internet users move frequently. They have one IP address in the morning,

another for lunch, a third in the afternoon at the coffeehouse, and a fourth

once they return to their table after ordering another latte. This mobility

complicates activating the wiretap at the local access provider.

It is worth noting that the worldwide GSM network, which despite its

insecurities was relatively secure for its time, required twenty years of

development. There were meetings with participants from all the European

Postal, Telegraph and Telecommunications services-at that time, most

European communications providers were state owned, not private-and

it cost billions of dollars. The network continues to have trouble with

CALEA-type interceptions. Wiretapping VoIP is much harder.

Requiring that collection be limited to the target of court orders and,

within that framework, to communications pertaining to the court authorization, is an important aspect of the U.S. wiretapping approach. The

mobility of VoIP communications makes isolating and tapping the proper

VoIP communication exceedingly difficult. A court could approve acquisition of an entire packet stream with the target communications isolated

afterward. There is precedent for this type of approach. For example, when

a private-branch exchange (the private switching centers used by large

institutions) is connected to the PSTN, the target's phone number is not

visible. In this case, a trunk-side wiretap is permitted, with the appropriate

call sifted out later.

This would not, however, solve the problem of securing the wiretapping

technology, which must be available at each and every possible local access

provider. This would mean securing the physical facilities of each of these

ISP's routers and switches as well as the logic of those same switches and

routers. Getting the security right is confoundingly hard. Many ISPs are

small and lack the ability to do so. Not only are Internet communications

insecure, attempting to architect them for real-time law enforcement wiretapping may make them even more so.

The underlying problem is that the PSTN-type model of wiretapping

does not extend to the Internet. The PSTN is a large "bricks-and-mortar"

business, requiring large investments in capital to build and run the wires,

radio towers, and networks for signal transmission for modern telephony.

The ISPs, by contrast, are built from commodity hardware, inexpensive to

purchase and run. So while some ISPs have millions of customers, there

are thousands of smaller firms servicing dozens of users. The archetype of wiretapping at a "Ma Bell" facility falls apart when the ISP is a VoIP provider with four employees.

The illegal wiretapping that occurred in Greece was very skillfully done,

but not all wiretapping needs to be so skillful in order to be successful. The

information that might be sought by a criminal or spy-specifications for a

new computer chip, the draft of a judge's opinion, a company's bid for new

sites for drilling for oil-might require wiretapping only for a brief period,

instead of the months of eavesdropping that occurred in Greece. Thus

tampering with the local ISP's wiretapping software to achieve illegal eavesdropping might not need the same level of expertise. Extending CALEA to

VoIP may well result in decreasing the security of VoIP communications.

8.4 Remote Delivery Creates Security Risks

It has become the norm for modern communication systems to remotely

deliver wiretap signals. CALEA expects it. It was done in the warrantless

wiretapping at the AT&T switching office in San Francisco. Norm or not,

such delivery creates risks.

A wiretap is a silent third party on a conference call, something that is

easy to implement in digital telephone switches. In opening up communications to an unacknowledged third party, wiretapping is a security

transgression. It increases the possibility that communications security can

be violated with minimal risk of discovery.42

What is needed to prevent such unauthorized eavesdropping is unimpeachable auditing systems for the surveillance. While such systems may

not prevent all cases of illegal wiretapping, their existence and ability to

aid prosecution provides a deterrence effect. The lack of auditing capabilities is part of what went wrong in Athens. This makes the auditing problems in the FBI's DCS system all the more inexplicable.

DCS3000 (formerly Carnivore) was developed for remote delivery of

wiretaps and pen registers at ISPs. This system is supposed to provide both

investigative and prosecuting tools, which require that the chain of evidence be unimpeachable. But FBI documents showed that DCS3000 had

numerous problems that could lead to major insecurities. The system used

an auditing scheme with shared user logins, which could easily be spoofed.

Auditing of who used the system depended on a manual log sheet.43 The

system was highly vulnerable to insider attacks. The same type of poor

auditing schemes Robert Hanssen used to check FBI's systems to see if the

bureau was onto him were still being put into FBI wiretapping systems

being built in the mid-2000s.

Remote delivery means that not only can information be exfiltrated

from an electronic surveillance; rogue software may be introduced. There

is increased risk of introducing a vulnerability into the communications

system. This could be the installation of a general wiretap capability or one

targeting a specific person.44

8.5 New Wiretapping Requirement Creates Threats to Innovation

The Internet has flourished because of its design that minimizes the constraints a new application must satisfy; innovation is cheap and easy. Or

it was until CALEA reared its head. One of the major advantages of VoIP

is cost savings,45 but CALEA compliance can be expensive.

In 2006 the DoJ Inspector General examined CALEA compliance and

noted that "a VoIP provider contracted to pay approximately $100,000 to

a trusted third party (TTP) to develop its CALEA solution. In addition, the

TTP will charge a monthly fee of $14,000 to $15,000 and $2,000 for each

intercept. 1141 Such a price is not a serious problem for an established communications provider, but it is prohibitive for a start-up. It can prevent the

development of new VoIP products. It can ensure that communications

providers do not add new features; the DoJ Inspector General reported that

"[telephone company] officials were concerned that the government would

mandate that every new feature would have to be CALEA-compliant prior

to being offered to the public.""