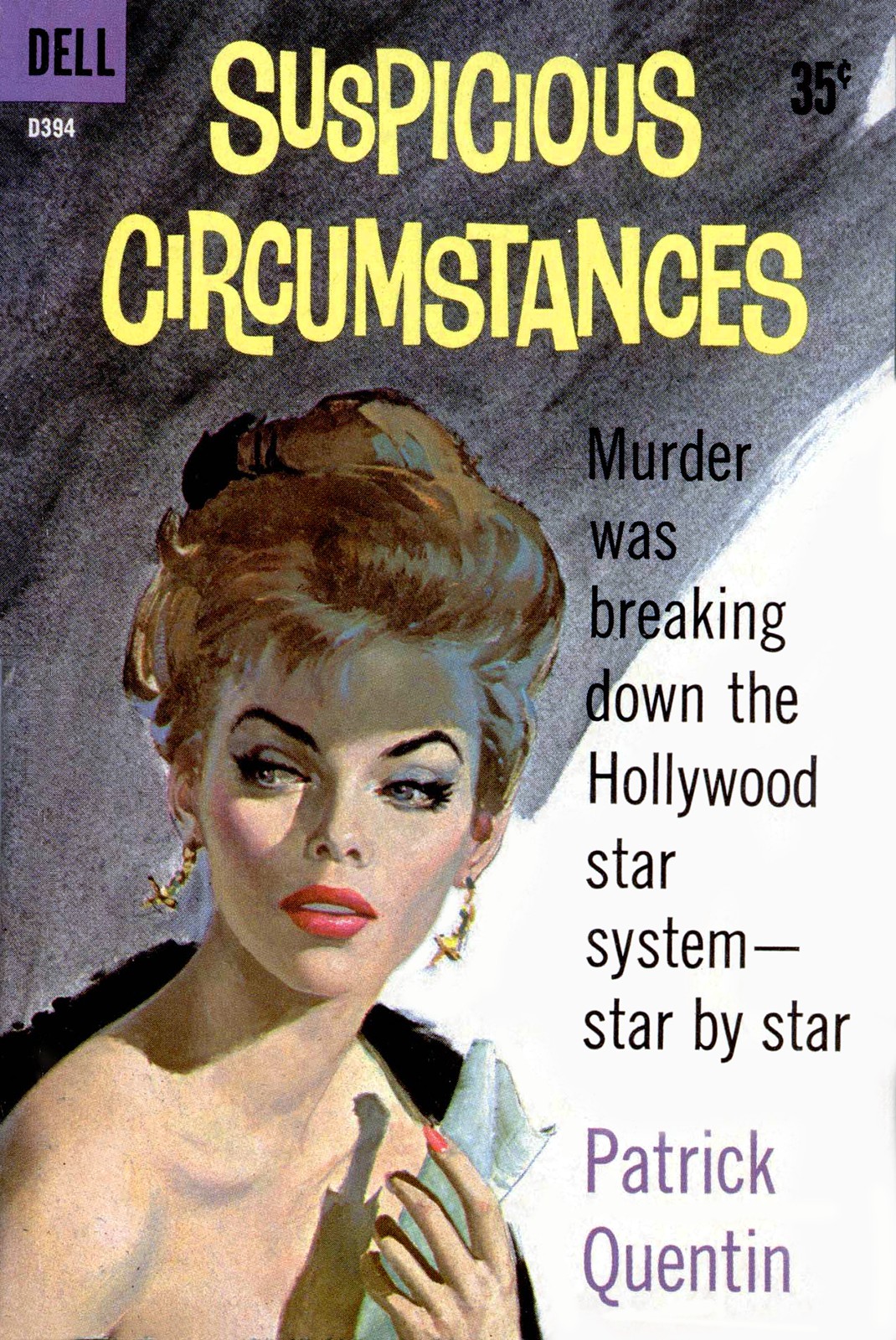

Suspicious Circumstances

PATRICK QUENTIN

SUSPICIOUS CIRCUMSTANCES

Copyright © 1957 by Patrick Quentin

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- About Patrick Quentin

- Bibliography

Suspicious Circumstances

I was in Paris when Norma Delanay died.

I’d decided to write a novel, and when I told Mother, she said, ‘A novel, Nickie dear? At nineteen? Well, why not? The young eye — so penetrating. Go then to Paris. That’s where the best books get written.’

Pam and Gino and even Uncle Hans protested that if I could write a novel at all it would come out just as well in Southern California and Pam did a lot of muttering about ‘wild extravagance’. They didn’t get anywhere, of course. No one ever got anywhere with Mother. The more the idea of my being a Parisian writer registered with her, the more it slayed her.

‘The Left Bank… La Vie de Bohème ... A little démodé, but so good for a growing boy…’

Next morning she drove me herself to the L.A. International Airport, wearing lounging pajamas and a Royal Pastel mink coat. She cried a little, kissed me with great warmth and signed autographs for awe-struck air hostesses.

‘Be good, Nickie darling. Write a lovely book and write it quickly, because I will miss you. But do not put in descriptions. The dome of Sacré Cœur floating like a bubble over the rooftops… Old women with mittens selling chestnuts.... So boring.’

Two days later I was installed in a suitably Vie de Bohème apartment looking out on the Luxembourg Gardens, which one of Mother’s innumerable French admirers had put at my disposal. The next week, at the Café Flore, I met Monique, who agreed with Mother that the best books were written in Paris but was convinced that they only got written by men who had girls like her to inspire them.

It didn’t take her long to have me equally convinced because Monique was about as inspirational as a French girl can get, and in a couple of days I’d forgotten my naive belief that the only attractive females were California redheads. I’d also, I’m afraid, rather forgotten about being a novelist because with Monique there always seemed to be so many other more relaxing things to be inspired towards.

That was the set-up then when Norma Delanay died. Monique and I were on our way to some highbrow cinema to see a revival of one of Mother’s early Hollywood movies. Mother that season — or rather Early Mother — was nosing Garbo out as the Culture Heroine of the Left Bank. A man, passing us on the Rue Vavin, was reading a

Paris-Soir

. Over his elbow I saw the French headlines. They said :

NORMA DELANAY PLUNGES TO DEATH IN LUXURIOUS BEVERLY HILLS HOME

I wanted to buy a paper and find out more about it, but Monique was scared of being late for Mother’s movie.

‘Miss a moment of the Great Anny Rood just because some trashy ex-sweater-girl becomes dead? Norma Delanay? Who cares a fig for Norma Delanay except perhaps elderly serving-maids in the American motels?’

I wasn’t an elderly serving-maid in an American motel, but I cared. Not deeply perhaps because at Hollywood parties ever since I could remember, Norma Delanay, who had represented sex to the American Public from 1940 to '46 or so, had always reached a dry martini moment when she’d sway around swimming-pools and clasp me to her sweaters and coo, ‘Anny Rood’s little Nickie. Isn’t he cunning? I could just eat him up!’ But even so, she was the first person I’d ever known who had died and, as an author, I felt it ought to mean something. Besides, Norma and her husband had recently been intimately involved with Mother and I had the uneasy feeling it was going to affect me some way or other.

But Monique won about not buying a paper, and soon we were sitting in a wildly gilded and statued movie-house which looked as if Madame Dubarry had used it for giving orgies, and were watching Mother in

Desert Wind

— the first movie she’d ever made in the States. Eighteen years ago it had been, a year after her one and only French movie had sky-rocketed her to fame from — let us face it — the gutter. I’d been exactly sixteen months old at the time.

I’d never seen

Desert Wind

. Mother wasn’t one of those celebrities who force you to admire their former triumphs. She lived too much in the present. While Monique was oohing and aahing about ‘bone structure’ and ‘divinity of movement’ and nuzzling against me, reminding me how very satisfactory my new life was, I looked at Mother and thought about Norma Delanay plunging to death.

It was a rather uncomfortable sensation because the Mother on the screen, deciding whether to become a nun or to go on being a wealthy woman of mystery from Belgrade with a sexy singing voice, was so absurdly like the Mother I had left a month ago at the L.A. Airport. Mother didn’t believe in growing older and her quality had never changed, not even the inimitable Was-it-Swiss? Was-it-Balkan? accent. Whatever it was that made her a legend had always been there from the beginning, and each time the great swooning eyes with their interminable lashes were ruining the hero’s chances of a better life, they also seemed, out of their corners, to be giving me that well-known ‘This-is-for-your-own-good-dear' check up.

‘Nickie, are you sure you shouldn’t be home finishing a chapter?’ ‘Nickie, are you sure that girl is suitable?’ And, most unnerving of all, ‘Nickie, how can you be thinking such boring thoughts about Norma?’

Because what I was thinking about Norma was indeed boring by our household’s standards, according to which ‘divine’ meant anything Mother had endorsed and 'boring' everything else. I was thinking that, when I left Hollywood, Norma’s producer husband, Ronnie Light, had fallen headlong in love with Mother. There were all sorts of reasons, involving a dreadful English actress called Sylvia La Mann, which kept it from being Mother’s fault, but there it was. And, since Norma’s career was moribund and her only remaining asset was being Ronnie’s wife, having her husband drooling over her 'oldest and dearest' friend wasn’t something she’d feel particularly festive about.

If there had to be a reason for her ‘plunging to death in her luxurious Beverly Hills home’, Mother seemed as good a one as any other.

Oh dear, I thought, envisaging appalling scandals, and Mother went on looking at me keenly from the screen while she decided not to become a nun after all but to return tragically to a life of pleasure.

Monique, who had been made very pro-American by the movie, insisted that the only culturally suitable next step was to go to a St Germain ‘cave’ where a ‘fabulous’ American colored trumpeter played 'le jazz hot'. I managed to buy a paper on the way and, in the dimmest light in history, while the trumpeter trumpeted and dozens of girls and boys in blue jeans, all looking exactly alike to me, drank cokes and hurled each other around in what seemed to them to be Rock and Roll, I read about Norma Delanay.

My languages were all right because Mother’s career had always been globe-girdling and, during my formative years, I had been dropped, off and on, into almost every type of educational establishment ranging from a lycée run by French monks in Saigon through a British Public School called St Cecil’s to a humiliating Dancing and Fencing Academy in Santa Monica. In fact, I’m the most International American I know, not only by schooling but by blood since my father was a Czech aerialist who broke his neck in a trapeze fall before I was born, while Mother was sort of Swiss. That is, her parents had been Swiss acrobats but had given birth to her in a trunk in Rumania or Bulgaria or one of the more embarrassing countries, thus making her Swiss or Rumanian or Bulgarian, whichever she happened to feel like being at the moment.

The

Paris-Soir

informed me that Norma’s plunge to death hadn’t been as melodramatic as I had supposed from the headlines. She had merely ‘slipped and fallen while descending the stairs, thereby breaking her neck’. I felt a distinct sense of relief. Heartbroken wives, planning to end it all, did not, it seemed to me, hurl themselves down their own staircases. It was delightfully easy to believe that Norma had just ‘slipped and fallen’, for Norma had in recent years seldom descended or ascended or even proceeded on the level without being saturated in gin.

The article was continued on an inner page, but I had to dance with Monique then because she was pouting out her lower lip and looking like a French girl who felt she was losing her inspirational quality. Eventually I got back to the

Paris-Soir.

On the inner page, after giving a brief outline of Norma’s undistinguished career, the article concluded as follows:

‘The death of Miss Delanay arrived at a particularly tragic moment since her famous Independent Producer-Director husband, Ronald Light, was just about to star her in a six million dollar Cinemascope spectacle based on the life of Ninon de Lenclos.’

I could hardly believe my eyes. Ronnie, the astute, realistic Ronnie, gambling away six million bucks on a hopeless comeback for Norma? Who had been twisting whose arm?

Monique, sitting next to me drinking coke, was pouting her lower lip again. ‘Mon Dieu, read, read, read. Is that all the American writers do when they are with their girlfriends? Read the journals?’

‘Who’s Ninon de Lenclos?’ I said.

‘Ah, mon pauvre petit barbarian, Ninon de Lenclos was one of France’s greatest courtesans.’

‘How old was she?’

‘Old? She was ancient. At ninety she was still having lovers.’

‘At least it was type-casting for Norma,’ I said.

Then a very horrid thought struck me. Mother, who hadn’t worked for a year, wasn’t exactly 'hot' in Hollywood. She wasn’t washed up, of course. You can’t wash up a legend. But even legends, when they get to be a little too legendary, don’t necessarily find lovely six-million dollar spectacles growing on avocado trees. Now that Norma had so conveniently plunged, who would be a natural to play this nonagenarian grande amoureuse? Who indeed?

Control yourself, Nickie, I thought. Smother that writer’s imagination. Norma fell down the stairs. Anyone can fall down the stairs. But for a moment I felt peculiar.

‘I can see it now,’ I blurted. ‘Mother in the tallest wig since Norma Shearer played Marie Antoinette. Did Ninon de Lenclos yodel? Mother can yodel too.’

Monique tapped her foot and with a great deal of snapping of eyes said, ‘Mother, Mother, Mother. How I detest the Great Anny Rood for giving her so charming son the Mother Complex.’

By then Monique of all people ought to have known that even if I did have a sort of mother-complex it certainly wasn’t the type that interferes with your love-life. But Monique was the kind of girl it’s a pleasure to reassure about almost anything, and after half an hour of that heavy French public smooching, we were both about as far away from a mother-complex as anyone could get. French girls, however, never become completely carried away. Long after I’d forgotten it, Monique still remembered she was living with one of those European-type dragon aunts who sit up clanking keys until their nieces come home as unblemished as they went out. So I took her home.

It was late when I got back to the Luxembourg Gardens, but I wasn’t at all tired. Although I went to bed, I didn’t fall asleep and insidious Californian thoughts started to creep back. They were negative, I knew, and should be suppressed. But the trouble with my love for Mother, as opposed to everyone else's, was that years ago I’d decided she was capable of anything.

Mother, I thought… Ronnie… Norma’s plunge… Ninon de Lenclos.

The sleep I fell into was uneasy.

Monique arrived next morning to make breakfast for us. That was another of the wonderful things about her. What American girl, even the most offbeat California red-head, would think about crossing Paris virtually at the crack of dawn to prepare croissants with honey and coffee, even though the coffee was rather odd and somehow involved boiling an egg?

While I was taking a lukewarm shower with the egg-coffee smelling delicious, there was a bang at the door. I heard Monique arguing with someone, then, just as I came out of the bathroom in my robe, she appeared in the bedroom with a cablegram.

I opened it. It said:

COME HOME IMMEDIATELY MOTHER

I looked at the cable. I looked at Monique. I was feeling dozens of things, but mostly I was feeling rage. Leave Monique? Now? Just when Life was Beginning? I tossed the cable to Monique and, running to the door and yelling down the stairs, caught the telegram man. He had a cable blank. On it I scribbled ferociously: