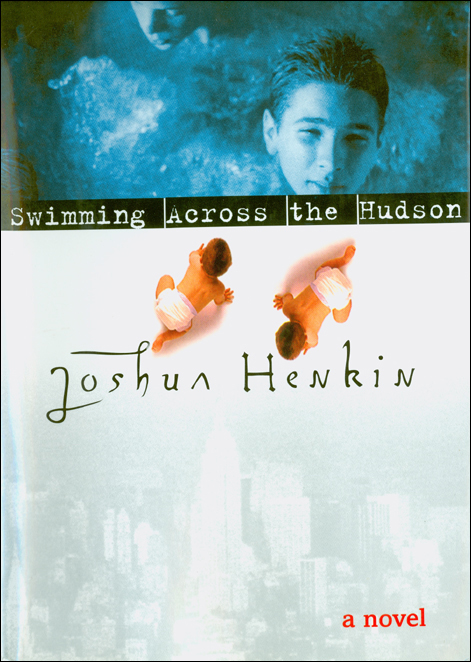

Swimming Across the Hudson

Read Swimming Across the Hudson Online

Authors: Joshua Henkin

Tags: #Adoption, #Jews, #Fiction, #General

SWIMMING ACROSS THE HUDSON

This novel is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events; to real people, living or dead; or to real locales are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 1997 by Joshua Henkin

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reprinted in any form without permission.

Published by G. P. Putnam's Sons

Publishers Since 1838

200 Madison Avenue

New York, NY 10016

Published simultaneously in Canada

The text of this book is set in Goudy.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Henkin, Joshua.

Swimming across the Hudson / Joshua Henkin.

p.

Â

cm.

ISBN 978-0-786-75552-3

I. Title.

PS3558.E49594

Â

1997

Â

96-41235 CIP

813â².54âdc20

3

Â

5

Â

7

Â

9

Â

10

Â

8

Â

6

Â

4

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Book design by Marysarah Quinn

I am grateful to the following people for their assistance: Andrea Brott, Armin Brott, Jason Dubow, Miles Ehrlich, Anna Jardine, and Abby Rose. I'm especially appreciative of Lisa Bankoff, Laura Gaines, and Faith Sale for all that they have done on my behalf.

Thanks finally to The Heekin Group Foundation and the Avery Hopwood and Jule Hopwood Fund for their financial support.

T

O MY PARENTS

,

A

LICE AND

L

OUIS

H

ENKIN

,

AND MY BROTHERS

,

D

AVID AND

D

ANIEL

SWIMMING ACROSS THE HUDSON

Contents

Â

T

here's a story I was told when I was a child.

My parents had friends who lived in Kansas. Their name was Millstein, and I pictured them clearly, swarthy and slow-afoot in the cornfield sun, a Jewish family camped in the heartland.

We lived in New York City and were more Jewish than the Millsteins. That is what my father said: more Jewish, less Jewish, my father always quantifying things, spinning out the lessons that would shape my life. “They

care

about being Jewish,” he said, “but what do you do with all that caring?”

My parents did this: They sent my brother, Jonathan, and me to Jewish day school; they kept a kosher home. On Friday nights my mother lit the sabbath candles. She placed her hands across her eyes and said a blessing to the sabbath queen.

I liked the scent of the sabbath, the perfume on my mother's wrists, my father's dress shirts bleached and ironed. I could smell the challah in the kitchen, the marigolds, red and yellow, arranged in their vase. I stood next to Jonathan with my hands behind my back and watched the candles flicker. We wore navy slacks and white oxford shirts, the two of us like twins with our hair slicked back, wearing matching clothes for the sabbath.

My mother had been born Jewish but grew up in a secular home. Her parents sent her to the Ethical Culture School and to summer work camp, where the kids stood in a circle before going to bed and sang “The International.”

“Mom's seen some weird things,” my father said once. My mother had studied anthropology in college, and had spent time in Bali after she graduated.

She smiled. “I've seen some weird things right inside this apartment.”

My father wanted Jonathan and me to be like himâto keep kosher and observe the sabbath, to pepper our conversations with the words of the Torah, the way his father and grandfather had done, generations of Jews speaking the same language, stretching back to Moses.

“Think about that,” my father said. “All Jews are related to Moses.”

My mother agreed to keep a kosher home even though she didn't believe in God. She learned a little Hebrew; she went to synagogue on the holidays. She liked ritual, she said, and that pleased my father. When we grew up, she told us, we could live as we wanted.

My father knew we'd live as we wanted. But I worried about what would happen if God spoke to him. In synagogue on Rosh Hashanah, we read about the binding of Isaac. I saw Abraham and Isaac in the land of Moriah, a butcher knife gleaming in Abraham's hand.

“Would you do that to me?” I asked my father.

“Don't be silly,” he said.

“What if God commanded you?”

“That's impossible. God doesn't speak directly to people anymore.”

“He could start to.”

“He won't, Ben. It's a counterfactual.”

“It's a counterfactual?”

“Right. It's counter to the facts.”

Still, I worried. I pictured us in Riverside Park, my father and me on a hill, the kids on their sleds flying by us. Above us hung the trees, windblown and bare, and above them the heavens. I imagined

my father holding a knife. He stood next to me with his eyes closed, listening patiently for God's command.

He taught Jonathan and me how to chant from the Torah. We learned prophets and Talmud; we read from “Ethics of the Fathers” after sabbath lunch. On the way to synagogue we conjugated Hebrew verbs, the three of us together keeping beat. Sometimes my mother would join usâ

amartee, amarta, amar, amarnu, amartem, amru

âthe four of us marching along Riverside Drive, one-two, one-two, the way my father had marched many years before, when he'd fought the Germans in World War II.

The Millsteins, though, were undereducated. They went to synagogue just on Yom Kippur, in a city an hour from their home. They lived in a town of three thousand people where they were the only Jews.

My father looked at Jonathan and me. He was a tall manâtaller than I imagined I'd ever beâand I was sure he understood the world.

“Do you know what synagogue is like in Kansas?”

I shook my head.

“It's like church,” he said.

“They pray to Jesus,” said Jonathan.

“No,” my father said, “they don't pray to Jesus, but the services are in English and no one knows what's going on. The cantor faces the congregants and sings to them. It's like a performance.”

“Like the opera,” Jonathan said.

“Exactly,” said my father.

The Millstein boys had had bar mitzvahs, but they weren't bar mitzvahs as we knew them. They were more bar than mitzvah, my father said.

“What does that mean?” my mother asked.

“It means everyone got drunk,” I said.

“It was an excuse for a party,” said my father.

The Millsteins gave money to the United Jewish Appeal. They

bought Israel Bonds and planted trees in the Negev and had a portrait of Golda Meir hanging in their living room. But this was cultural Judaism, my father said; it wouldn't protect them.

“Protect them from what?” I asked.

“From intermarriage,” he said. “From Kansas.”

For this was the heart of my father's story. Peter, the Millsteins' eldest son, graduated from college and took a trip around the world. He backpacked through Asia and North Africa, and ended up in Israel, where he worked on a kibbutz, picking melons in the fields. This pleased his parentsâtheir son the Zionist, tilling the soil. They felt fortunate, they said, Peter in a country with all these Jewish girls, and now he might marry within the faith.

But he didn't, my father said. Even in Israel he found a non-Jewâa Swedish girl who worked on the kibbutzâand a year later they got married.

For several seconds my father just stared at us. Then he said, “Do you see my point?”

He was a smart man. He taught political science at Columbia University; he spoke Russian, Italian, German, and French. At night I would find him reading in the living roomâbooks about countries whose names I didn't know, about abstract painting and French literature, about memory, personality, and the workings of the brain. He was a genius, I thought, but I didn't see his point. Marrying a Swede had nothing to do with Kansas.

But I didn't tell him that. And over time, I forgot about the Millsteins.

Then, twelve years later, I too graduated from college and took a trip. I was with a friend driving west, and I called my parents when we got to Kansas. I wanted the Millsteins' phone number.

My father sounded nervous on the other end of the line. “Please, Ben,” he whispered, “don't do this.”

“Don't do what?”

“Just please don't call them.”

I was standing at a pay phone along the edge of the highway; I watched a stream of trucks drive by. And it occurred to me then, in this town I'd never been to, that all these years my father had lied to me. I pictured the Millsteins: hoe in hand, dreidel in pocket, Eastern Europe come to the Dust Bowl. But I could hear it in his voice, the Millsteins weren't real. They were nothing but a lesson.

I'm thirty-one years old now. I live in San Francisco with Jenny and her daughter, Tara; Jonathan lives a mile away from us. Sometimes from my balcony on a clear afternoon I imagine I can see his house.

Jonathan and I are adopted. It's something we've always known, as much a part of us as our bodies, what we have been and always will be. For a while we were embarrassed, for a while we were proud, for a long time Jonathan has been indifferent. Throughout it all my parents considered us their children, said they loved us no less for how we'd arrived.

But last year, without warning, I got a letter from my birth mother. Since then everything has changed.

Sometimes, even now, I think about the Millsteins. I try to remember the things my father taught us, the prayers he said, his wishes for our lives. But Jenny isn't Jewish, and Jonathan is gay, and I see my father in our old apartment, asking my mother where he went wrong, how things might have been different.