Switchers (20 page)

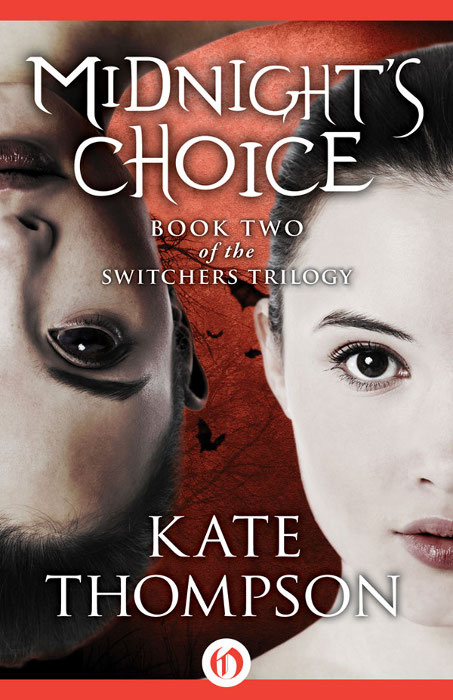

Authors: Kate Thompson

Reluctantly, Tess turned her back on the bright lights of her parents’ house and returned to the shape of the brave little seabird. On tired wings she crossed the city and searched among the snowy fields and trees for the ruin of the big house and the little cottage beside it. When, after some time, she found it, she was relieved to see smoke rising from the chimney and paths cleared to the sheds. She landed on the roof of the hen-house and looked around for a while before she decided on the best way of getting into Lizzie’s house without alarming her.

The other cats arched their backs and hissed when they heard the stranger come in through the cat-flap and scratch at the kitchen door, but Lizzie knew straight away.

‘You’s back!’ she said as she opened the door. ‘That was quick!’

Tess Switched, and the cats scattered into the corners of the room. Lizzie looked at her in concern. ‘You’s worn out, girl. What’s happened?’

Tess flopped, exhausted, into a chair. The seat had been warmed by the cats, and for a long time Tess sat in silence, letting the warmth sink into her and waiting for her strength to return. Lizzie went over to the sink and set about making tea, but she did it quietly, and Tess forgot that she was there until the cup was pressed gently into her hand. She sat up and sipped the sweet tea, but still she could not speak.

‘Rat-boy, huh?’

Tess looked up. Above the hob in the fireplace, a twitching brown nose was poking out of the hole. An unusually long nose. Tears began to pour down Tess’s cheeks. Lizzie took off her slipper and threw it at the hole. Long Nose squeaked and disappeared, but a moment later he was back.

‘Nanananana,’ he said. ‘Tail Short Seven Toes curled up with Long Nose and Nose Broken by a Mousetrap. Us guys sleeping. Sun rising, us guys bright eyes, hungry and strong.’

Tess nodded through her tears. ‘He’s right, Lizzie,’ she said. ‘You and I can talk in the morning.’

‘Off you go, then,’ said Lizzie. ‘But don’t forget to come back to me, will you?’

‘Of course not.’ Tess gulped down the last of the tea, then put down the cup and Switched. As soon as she was a rat again, she felt better. Rats live together closely, but without attachment or sentiment, and although Kevin’s death was still an absence, it was no longer a loss or a cause for grief. She shook herself and began to groom, to put herself back in order, but Lizzie picked her up and lifted her to the hole in the chimney breast before the cats could catch sight of her. There she touched noses with the other two, and quite dispassionately told them her adventures as she followed them through a twisting network of passages and underground tunnels. Long Nose loved the story, and made her tell the bit about the meeting with the first krool again and again, until eventually they arrived at their destination, a snug nest beneath the cowshed. Tess curled up close against Nose Broken by a Mousetrap, and the last thing she heard before she fell asleep was the sound of Nancy above her head, drowzily chewing the cud.

The next morning, Tess made her way back to the cottage, and, in human form again, told Lizzie everything that had happened. The old woman listened carefully, slapping her knees with delight at each new development in the story. When Tess had finished, they both sat quietly for a few minutes, then Lizzie said, ‘If I remembers right, you likes pancakes for breakfast.’

Tess looked over at her in astonishment. ‘How can you think about pancakes, Lizzie? Aren’t you upset about Kevin?’

‘No,’ said Lizzie. ‘I isn’t. There are those who say there’s life after death and those who say there isn’t. But until I gets there myself, I isn’t in any position to say one thing or another.’

‘But that isn’t the point,’ said Tess. ‘I’m sad because I won’t see him any more.’

‘Then you’s sad for yourself, girl, not for Kevin.’

Tess looked into the fire. The flames were just taking hold of the wood, leaping up towards the kettle, sending sparks up to disappear into the darkness of the chimney. Lizzie got up and began to crack eggs into a bowl.

‘Maybe you’re right,’ said Tess. ‘I don’t know. But the thing I can’t understand is why it should have been us. I mean, why was I born a Switcher, and Kevin. And you, why you?’

‘But all kids is Switchers,’ said Lizzie. ‘Didn’t you know that?’

‘What do you mean? How could all kids be Switchers?’

Lizzie began to beat flour into the eggs. ‘All kids is born with the ability. But very few learns that they has it. You has to learn before you’s eight years old, because after that your mind is set and you takes on the same beliefs as everybody else. A lot of kids find out they can Switch, but when their parents and friends say it’s impossible, they believes them instead of theirselves, and then they forgets about it, like they forgets everything that doesn’t fit in with what everyone else thinks. It’s only a few who has enough faith in theirselves to know that they can do it despite what the rest of the world thinks.’

‘So was it all just chance, then? Just coincidence?’

Lizzie was beating furiously at her batter. ‘Chance?’ she said. ‘Coincidence? I doesn’t know what the words mean.’

A movement in the chimney breast made Tess look up. One crooked nose and four small ones were poking out of the hole, and five pairs of eyes were fixed upon her. ‘Grandchildren,’ said Nose Broken by a Mousetrap. ‘Tail Short Seven Toes telling krools, mammoths, dragons, little ones watching.’

The four small noses quivered in nervous anticipation. Tess laughed and, while Lizzie fried the pancakes, she told her story once again.

Tess’s parents were astonished to see her arriving home. They had forgone the chance to escape the weather and flee to southern Europe and had stayed in the seized-up city instead, in case Tess returned. When the snow began to melt and the roads were cleared their hopes rose, but by the time she finally knocked on the door they had almost given up on her. They greeted her with tears and laughter, and there was much talk of forgiveness and all being well that ends well.

But they found it difficult to adjust to the changes that had happened to Tess. Because although the date told her that it had not been so long since she left her bedroom window in the form of an owl, by another reckoning it was a year, a lifetime, an ice age. She could barely remember the child that she had been.

Tess had always been aloof, preferring her own company to that of others, but now it was more than that. She had become a stranger to her parents, and in all the years that followed they never learnt more about her absence than they had heard from Garda Maloney’s report. All they knew was that she had been away with a boy, and that she would not or could not discuss the matter. It was clear from her withdrawn behaviour that in some way or other it had ended badly, and they believed that she would tell them about it when she was ready.

So, although they noticed that from time to time Tess wore a silver ring that they had never seen before, they didn’t ask her about it. They left her alone and tried to resume the family life of old. Tess tried, too, but it was clear to all of them that she was acting mechanically and not from her heart. She made an effort at school, and succeeded in making one or two friends, but that was mechanical, too, and superficial. It helped to pass the time, but it did nothing to relieve the deep loneliness she felt. Nor did her occasional trips to the park, to join with squirrels or birds or deer for an hour or two. She was not a part of their world, she knew, and nor was she a part of the world of home and school. She was somewhere in between, and all alone.

And her sense of isolation increased whenever she turned on the TV or radio and heard them talking about the famous ‘Northern Polar Crisis’. The krools, as she suspected, had retreated back into the ice cap and left no trace of their passing apart from the mysterious barren pathways which stretched for hundreds of miles through the vegetation in the Arctic Circle. A thousand theories were put forward, and it seemed that there was a new one getting aired every week. Each was as ludicrous as the last, but what really made Tess’s blood boil was the unanimous agreement that General Wolfe and Scud Morgan were the heroes of the day. And no human being apart from herself and Lizzie would ever know the truth.

Tess’s parents never reproached her, but she knew that they had suffered a lot when she disappeared. They didn’t try to stop her going for her walks in the park, but they made her promise never to be away for more than two hours and never to go out at night without telling them where she was going. Tess knew that in their terms it was a reasonable request and she agreed. She was sure that in time they would come to trust her again, and she would have more freedom, but in the meantime she would have to live without seeing either Lizzie or her friends the rats.

So she had to look elsewhere for comfort. She saved up her pocket money until she had enough to buy the biggest cage in the pet shop and the nicest white rat they had. Her parents were surprised, because Tess had so often expressed her disapproval of keeping animals in captivity, but they didn’t object.

But the rat turned out to be a terrible disappointment. It was terrified of the brown rat that she turned into, and terrified to leave its cage. When she did finally tempt it out into the room, it was timid and clumsy and slow, and no amount of persuasion would bring it to attempt the stairs. The worst of it, though, was that the poor, stupid creature could not even speak Rat. It had been born and brought up in a cage like its parents and grandparents, and it had never been allowed, much less encouraged, to use its intelligence. It had a few basic words-images, but beyond that it was mute, and no effort on Tess’s part succeeded in teaching it. The white rat was a mental infant, and would remain that way all its life.

It was company, nonetheless, and quite often Tess would lie awake at night, listening to it exercising itself on the wheel and talking baby-talk while she mulled over her experiences and thought about the decision which would face her in another year or so, when she turned fifteen. Time after time she dreamed of the possibilities, weighing the peaceful lives of dolphins and whales against the briefer but more thrilling lives of rats and goats. Time after time she seemed to reach a satisfactory decision, only to remind herself of how heart-broken her parents would be if she were to disappear from their lives for ever, without explanation. And on a particular night a few days after New Year, she had just reached the point, once again, of deciding to stay human, when something happened that was to make her think all over again, in an entirely different way.

It was the white rat’s sudden silence that pulled her out of her reflections and alerted her to the change in the atmosphere. She watched it sniff the air, then turn around and gaze steadily into the darkness outside her window. The hairs prickled on the back of Tess’s neck as she got out of bed and crossed warily to the window to look out.

There, on the same tree that the owl had once called from, was the most beautiful bird she had ever seen. It was familiar to her, somehow, and yet she was sure that she had never seen it before, or any other like it. Its bright feathers glowed in the light cast out from her room, and its tail hung down below it, way longer than its body. Then, suddenly, Tess remembered the page of the book where she had seen the bird pictured, and even before she noticed that it had only three toes on its right foot, she knew that it was Kevin. She knew that he had learned, in the nick of time, to find for himself the invisible path which lies between what is and what isn’t. As he had fallen, burning, that autumn night which was the eve of his birthday, he had made his final, irreversible Switch, and become the only creature, either of this world or not of it, that could survive that raging fire. And when the helicopters had left the following morning, he had appeared again, rising from his own ashes; a beautiful, golden phoenix.

Tess’s heart leapt, racing ahead of her into the night skies where she would soon be flying beside her friend. With a silent apology to her parents for breaking her promise, she reached for the latch and pushed open the window.

Turn the page to continue reading from the Switchers Trilogy

T

HE WHITE RAT WATCHED

as the two golden birds rose up into the night sky and disappeared from view. A few minutes ago, one of them had been his owner, Tess. Then she had seen the other bird on the tree outside her window, and she had shimmered, changed, and flown away. For a moment or two the rat remained still, staring into the empty darkness in perplexity, then he twitched his whiskers, washed his nose with his paws and jumped back on to his exercise wheel.

As she soared up high above the park, Tess had no thought of what she had left behind her. In her young life, she had used her secret ability to Switch to experience many different forms of animal life, but she had never been a phoenix before. All her attention was absorbed by this new and exhilarating experience, and until she had become comfortable with it, she could think of nothing else.

She followed the other bird faithfully as he rose through the night sky, higher and higher. Each sweep of her golden wings seemed effortless, and propelled her so far that she felt almost weightless. Behind her, the long sweeping tail seemed to have no more substance than the tail of a comet. It was as though the nature of the bird was to rise upwards; gravity had scarcely any power over it at all.