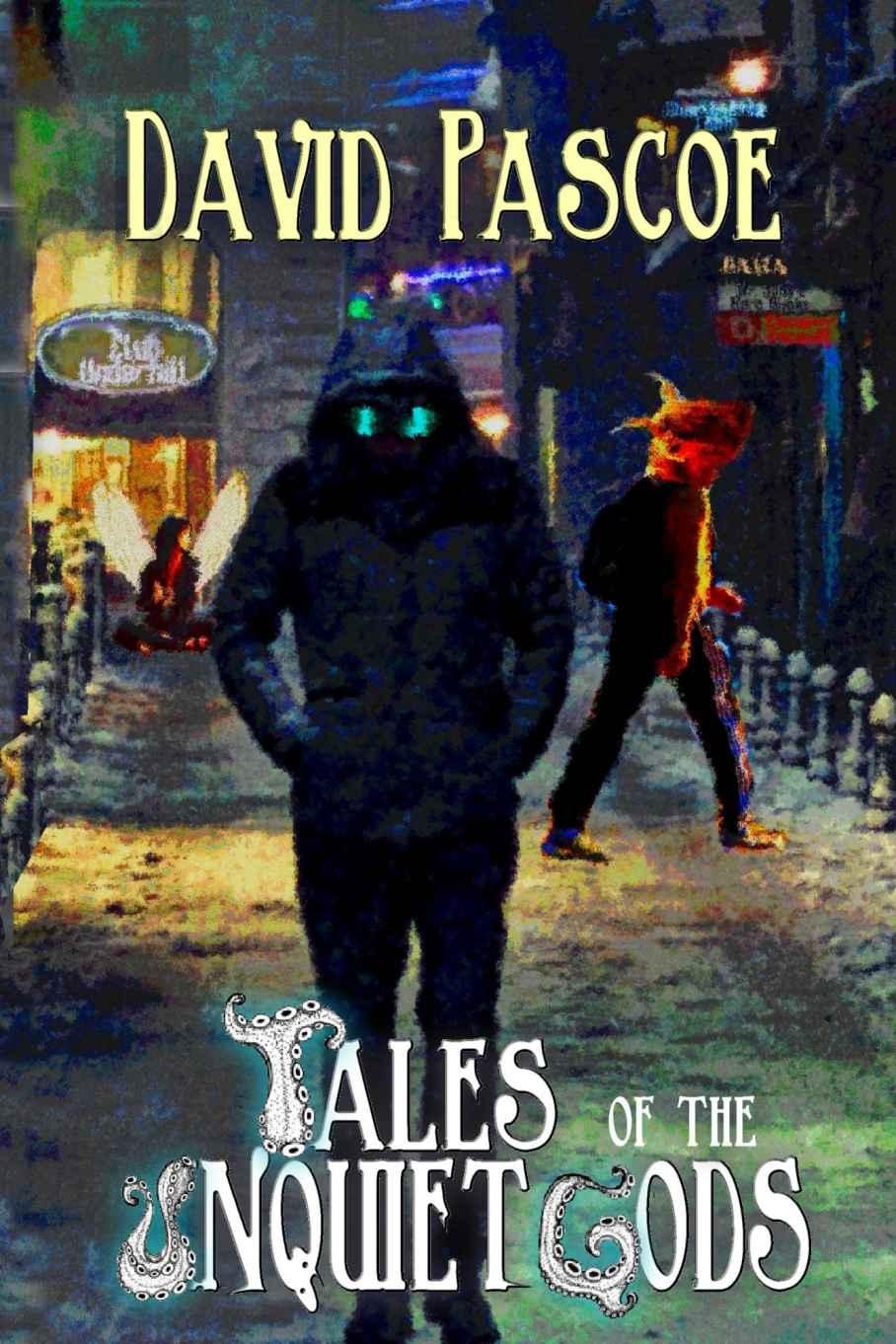

Tales of the Unquiet Gods

TALES OF THE UNQUIET GODS

Tales of the Unquiet Gods

A Collection

by

David E. Pascoe

Previously published as:

Shadow Hands

Fallen Knight

Heal Thyself

By Hands and Knees

Wizard Training

Within Range

COPYRIGHT

This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional. Any resemblance to real persons or incidents is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2016 by David E. Pascoe

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

A Scribe’s Blood Press Original

ISBN 978-0-9899053-8-1

Cover design by Sarah A. Hoyt

First edition, July 2015

DEDICATION

For Sal, who poked and prodded and challenged.

Thank you, my friend.

And for David E. Snow,

Who fueled an early hunger for story.

I’m sorry you never got to see this, Mor Far.

TALES OF THE UNQUIET GODS

Tales of the Unquiet Gods

A Collection

by

David E. Pascoe

PART ONE

SHADOW HANDS

1

Lights flickered off slick white tile, and the shadows created reached for her. Mellie gulped and pushed off the sink. The bite of disinfectant mixed with human effluvia burned in her nostrils, but the only smell of which she was conscious was the reek of her own fear.

She'd seen the shadows take people.

She shuffled her feet, taking desperate care to not bump into anything or catch a heel on a crack in the bathroom floor. Heart bumping against ribs, Melody Devreux ached to turn and run, but it was all she could do to move slowly - oh, so slowly - backward. Cold comfort was the knowledge that the shadowy hands, full of too many fingers and each of them clawed, had never yet managed to reach her.

Her left hand clenched tight on the handle of her fiddle case, knuckles white. The usually-warm wood was worn smooth by the grip of more hands than she knew. When Daddy had still lived with them - back when they were happy - her parents had given her Grand-père Devreux's fiddle. Dad could sing beautifully in a rich baritone, but his fingers were roughened by his trade, and unfit to handle the precious instrument. He'd always said they'd never been as clever as hers anyway.

Mellie backed slowly through the door, almost bumping into a rumpled bag-woman pulling a small cart piled high with the detritus of the city. Mellie squeaked when the bag-woman snarled at her. The face full of noxious breath redolent of rotting teeth turned her stomach, and she stammered an apology and tried to become one with the wall as the half-crazed old street dweller stumped into the recently vacated ladies room.

She could feel herself starting to relax when she heard a muffled screech from inside the door. One often heard such noises in the city. Sounds that, upon first hearing them sounded strange and out of place. Sounds that upon reflection you knew as just a tire screeching on pavement, or a cat suddenly surprised, or maybe a passerby knocked off-balance.

But this wasn't that kind of sound. The bag-lady's shriek still rang in Mellie's ears, distorted and far more distant than the few feet and a door between them should have made it. Against her will and in league with her dread, Mellie's toe nudged the door open a bare inch.

The harsh, fluorescent lights flickered, baring the bag-lady's fallen handcart and scattered belonging. Of the old woman herself, there was no sign.

Until, by sick chance, her gaze was drawn to the wall opposite the door. A trick of the light gave the impression of a figure picked out in the tiles, all shades of white and grey. The bag-lady's eyes, no longer surly, but now more than half crazed, bored into Mellie's. Begging for help, pleading for release from the clawed shadow hands that pulled her deeper into the wall.

And then the lights flickered again. The old woman was gone completely. The door swung closed.

Mellie jammed her fist in her mouth, stifling to a whimper the scream trying to claw its way out of her throat. The wool of the gray half-gloves Mama'd knit her was rough as sandpaper against lips chapped from the chill air. Her skin - all over, not just that little bit exposed to the air - prickled, chilled from a cold not in the least physical. Despite the air that tried to suck the warmth from her, and in sharp contrast to the blood boiling as her fear-frenzied heart drove it through her veins.

Mellie's blue eyes swiveled feverishly in their sockets as her gaze skittered over the morning crowd in the subway station. Her desperation to escape faded the colors she saw to muted grays. The innocent looks people directed toward her took on ominous import.

She fled.

Movement seemed safer, though she didn't know why. She walked, her steps jerky and mechanical, up the stairs and onto the street. The sun's warm light on her skin slowed her racing pulse. The mute terror receded, granting Mellie a few snatched moments to remember.

She couldn't remember, anymore, a time when she hadn't seen the shadows reaching for her. Her fear was her constant, hated companion. She didn't understand why she wasn't gone as completely as the poor bag-lady, as disappeared as she believed her father had been.

Mama didn't understand her frantic insistence on sleeping with a light on, or why she refused to go out after dark. Yet she knew her mother harbored the same fear of the dark.

Dawn and twilight were the worst, those times when the light was just strong enough to cast shadows. Shadows that were solid, almost physical things. Tricks of the dark. Hungry tricks that stretched devouring fingers.

Mellie's wandering feet pulled her to a park. Not a big one, just a patch of grass with a few trees and bushes. The sun rained enough warmth and light down to ease her terror just a bit farther back into the dark of Mellie's mind.

With a glance at the sun's position in the sky, she decided she could chance a few songs. She stepped off the sidewalk, and the green of the leaves around her warmed her in ways her coat and sweater hadn't.

Despite the chill in the air, she slipped out of her shoes and worked her bare toes into the sparse grass. Squatting on her heels, her breaths slowing and deepening, Mellie laid her fiddle case on the ground. She was confident the cracked leather and wood of the case would stand up to the morning dew that lingered in the wan light of the autumn morning.

Carefully positioning the case so it was in the most direct light - and would consequently cast the least shadow - Mellie pulled at the old brass latches. The metal, bearing a fine patina from years of players hands, moved easily. A testament to her care, though the couple drops of oil were the least of the maintenance she lavished on her prize.

Passersby began to notice Mellie as a piece of the world that didn't - quite - fit into their routines. She drew curious glances as she opened the small door in the case and pulled out a cake of rosin. She swiveled the catches and removed her bow, taking a moment to ensure the threads were tight enough, but not too tight.

She took care to draw the bow across the rosin as she'd been taught by Grand-père before he, too, had gone. The sharp, pine scent woke memories of happier times, when her parents had taken a small Mellie Devreux out of the city and into the woods.

She'd been amazed to see so many trees in one place, and ran and ran through their brown and gray trunks. She'd loved the shadows in the forest, cast by a strong summer sun through bright green leaves. The light had barely filtered through, creating soft patches of deep, inky darkness. But a darkness full of warmth, and life, and - not security, by any means - but a kind of wild, passionate love.

But that was long ago, before grasping shadows began to pull people into walls.

She drew the bow swiftly a few times, and then carefully, inch by inch to ensure the whole length of the threads was thoroughly coated. She didn't plan to play long, but the tunes she loved best were the ones Grand-père had taught her, the folk songs of his native Normandy. When she played them, though, the Celtic wildness poured through the sprightly notes in a way that scared her just a little.

She put away the rosin, leaving the case open on the ground, and lifted the warm, wooden violin out of the cradling velvet of its case. She carefully checked the strings, plucking them quietly and tuning from what she heard.

With a deep breath, she leapt into tune. The notes tripped over each other as the bow slid back and forth across the strings. Mellie's eyes were shut tight in fierce concentration, trying to escape - if only for a moment - the deadly frightful place her world had become.

Trying, and succeeding. As music poured forth from her, spilling from her fingers, the terror faded. The shadowy claws disappeared from her her mind. Her pulse raced, yes, but from the fierce joy of creation. Melody loved making music. Mama used to joke that Mellie had gotten all the talent she'd never had. Now, she pushed it out of her hands, out her fingers and through her fiddle.

Even the sun seemed brighter through her closed eyelids.

Melody's music, redolent of wilderness, deep forests and the complex interplay of life, wrapped around the pedestrians walking past. Though she didn't know, couldn't know, none of these would feel the horror of dark, ethereal hands reaching out of black un-places to pull them from existence. Their hearts were buoyed up by the slender young woman standing barefoot in the grass, by her bewitching music.

Several even dropped money into her case as they went on their disparate ways. Busking was legal, though somewhat looked down upon.

Unless it was good.

Song flowed into song, and Melody played. She played to hold back the bone-gnawing, soul-staining fear. She played for the wild joy that gripped her and soothed her skittish heart. She played for the memory of her father and of Grand-père. Her fingers flashed as the notes became a cataract of sound.

An unseen observer wondered at her passion, at her power. He flipped a coin toward her case, and blessed her for the pleasure she'd brought him. The coin flew lazily through the air, scattering sunlight from its shiny surface as it tumbled through the air.

Mellie saw the glint of the coin through her eyelids, so bright was it. But she was consumed by her art, and unconscious of it.

Melody played until her fingers hurt and her heart didn't. She played until cold, gray buildings blocked the afternoon sun from her face. Her fears, now only a pale imitation of the consuming thing they'd been, made her skin prickle. She should be getting home.

Mellie bent to put away her fiddle, and started. Her case was full of money. Ones and grubby change, mostly, but as she sorted through it, she received another shock. Nestled among the legal tender lay a gold coin. Somehow, she knew the luster was genuine. It was no larger than the pad of one of her fingers, with an irregular edge. The figures on either face were worn into illegibility. She thought one might be a face, and the other some kind of animal. And the coin weighed heavy in her palm.