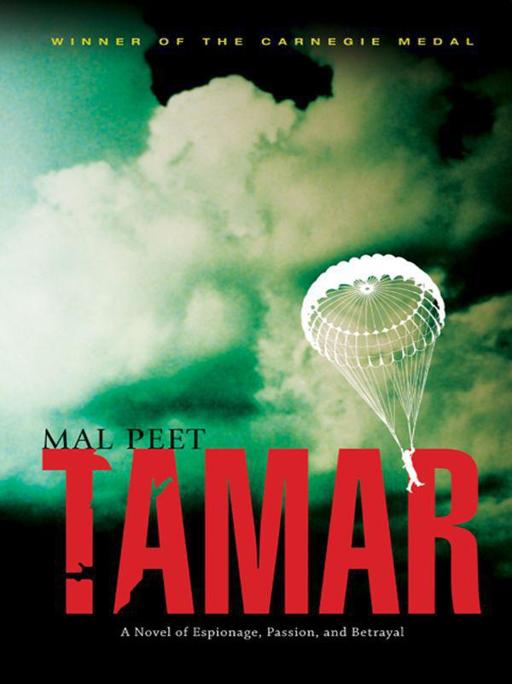

Tamar

Authors: Mal Peet

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or, if real, are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2007 by Mal Peet

Cover photographs: copyright © 2008 by Keystone/Getty Images (paratrooper); copyright © 2008 by Tomek Sikora/Getty Images (sky)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher.

First U.S. electronic edition 2010

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Peet, Mal.

Tamar / Mal Peet. — 1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

Summary: In England in 1995, fifteen-year-old Tamar, grief-stricken by the puzzling death of her beloved grandfather, slowly begins to uncover the secrets of his life in the Dutch resistance during the last year of the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, and the climactic events that forever cast a shadow on his life and that of his family.

ISBN 978-0-7636-3488-9 (hardcover)

[1. Grandfathers — Fiction. 2. Guilt — Fiction. 3. Netherlands — History — German occupation, 1940–1945 — Fiction. 4. World War, 1939–1945 — Underground movements — Netherlands — Fiction. 5. England — Fiction.]

I. Title.

PZ7.P3564Tam 2007

[Fic] — dc22 2006051837

ISBN 978-0-7636-4063-7 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-7636-5214-2 (electronic)

Candlewick Press

99 Dover Street

Somerville, Massachusetts 02144

visit us at

www.candlewick.com

Table of Contents

Dedication

Prologue: London, 1979

England, 1944

England, 1995

Holland, 1944

England, 1995

Holland, 1945

England, 1995

Holland, 1945

England, 1995

Holland, 1945

England, 1995

Holland, 1945

England, 1995

Epilogue: Amsterdam, 2005

Notes and Acknowledgments

About the Author

In the end, it was her grandfather, William Hyde, who gave the unborn child her name. He was serious about names; he’d had several himself.

Cautiously, when he and Jan were alone in the neglected little garden, William said, “Son, about this name. If the hospital is right and the child is a girl.”

Jan was watching a tiny silver speck cut a white furrow in the blue sky. “Oh, Gawd. Forget about it,” he said wearily. “We’ll sort it out eventually. There’s still seven weeks before the baby’s due.” Then he looked across at his father, perhaps sensing the old man’s gaze on his face. “Why? You got a suggestion?”

“Yes.”

Jan’s eyebrows went up. “Really? What is it?”

“Tamar.”

“How do you spell that?”

William spelled it out and Jan said, “Is that an actual name? Is it Dutch, or something?”

“No, it’s the name of a river. It separates Devon from Cornwall. Rivers are fine things to be named after, but that’s not what matters. As a word, as a name, what do you think of it?”

Jan thought about it, the shape and the sound of it. “Yeah, it’s rather nice, actually. Now tell me why. Why

Tamar

?”

His father took a while to answer. It was his way; Jan was used to it. He waited. From the open French windows, a scrap of his mother’s voice, then Sonia’s laughter.

“It has to do with the war,” he said.

This was interesting. Jan knew that his parents had been with the Dutch resistance during the Second World War. When he was a child, fussy about his food, Marijke had told him stories of rationing and hunger and people who would kill each other for a chicken. His father, though, had said almost nothing about those years. Not voluntarily. And now this.

“You know that I was an SOE agent.”

“That’s about all I do know. You’ve never told me much about it.”

“I’ve never wanted to. Psychologists tell us that keeping things buried inside is bad for us, makes us sick. Maybe it does. But I happen to think there are certain things that are best left buried, that we should take to our graves with us. Terrible things that we have witnessed. I’m sure you disagree. You belong to a liberated generation; you believe in freedom of information. But I am sure that one day you will change your mind.”

Jan didn’t know what to say. This was startling stuff, coming from his old man.

“SOE agents were trained in groups,” William Hyde said. “Each agent had a code name; these were chosen by the British, not us, and they were quite eccentric. Early in the war there was a group named after vegetables, if you can believe that. Several men and women went to their deaths having to call themselves things like Parsnip and Cabbage. So I was relieved when the code names chosen for my group were the names of rivers in the west of England: Severn, Torridge, Avon.”

“Ah,” Jan said. “And Tamar, of course.”

“Yes. And Tamar.”

“So,” Jan said, after another pause. “What you want, what you’re asking, is . . . I’m not sure how to put it. You’d like your grandchild to, what,

commemorate

you. Is that right? You’d like this code name to continue after you’ve . . .”

“I would consider it an honour.”

Jan almost laughed at this stiff and formal phrase.

“But only if you are sure you like it,” William said.

“I like it. But aren’t you forgetting something?”

“No. Sonia needs to agree, of course. But you’ll discuss it with her?”

“Sure. Don’t get your hopes up too high, though. If I say I like it, she’ll probably hate it. That’s the way it is.”

His father considered this. “In that case,” he said, “it might be best if you didn’t tell her why I suggested it.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, she might not like the idea of a name that is connected with . . . well, with war. With that period of time. She might think it is . . .”

“What? Sinister, or something?”

“Something like that, perhaps.”

“I don’t see why. You were fighting on the right side, after all.”

His father nodded. “True.”

Jan studied his father’s face for a second or two. It was so damned hard to know what the old man was feeling. He was like one of those office blocks with tinted windows; you could only see in if you happened to look from a certain angle when the light was right.

“It’s not a problem for me, Dad,” he said. “Anyway, it’s the name of a river, as you say. Come on, let’s go inside.”

The following day, Sonia and Jan went to his parents’ house for lunch. It was a monthly ritual that Sonia, in her present condition, found challenging. Marijke’s Sunday lunches were no-holds-barred affairs.

While they ate the first course, William Hyde kept darting glances at his son and daughter-in-law. They seemed a good deal happier than they had the day before, but that meant nothing in itself. It was not until Marijke was serving the roast beef that Sonia reached out and put a hand on her husband’s arm.

“Oh, come on,” she coaxed. “Don’t keep your poor old dad in suspense. Tell him.”

“Aha,” Marijke said, sliding a thick slice of red-centred meat onto Sonia’s plate. “What’s this? Some good news?”

Jan put his hands palms down on the table and leaned back, grinning. “It’s a miracle,” he said. “Sonia and I actually agree on a girl’s name. Thanks, Dad. Well done.”

Marijke was pouring gravy onto Sonia’s plate. She looked up, puzzled. “Name? What name is this?”

Sonia said, “Tamar. It’s perfect. I love it.”

Marijke dropped the jug. It fell onto Sonia’s plate, snapping a chunk off the rim. Gravy ran across the table and, before anyone could react, spilled onto Sonia’s distended belly.

The air shook; you could feel it. And the noise was unbelievable. It is probable that humans had never heard anything like it, since it was perhaps the sound of the planet giving birth to its mountains, of raw young continents grating together. In the fields of southern England, animals panicked and continued to panic because the noise would not stop. At a stables in Buckinghamshire, every horse kicked out the door of its stall and bolted. Near Mildenhall, in Suffolk, a line of military vehicles came to a halt, and men tumbled out of the trucks to stare at the sky. A doctor, driving with his head out of the window to look upwards, ran into the back of the convoy and was killed instantly.