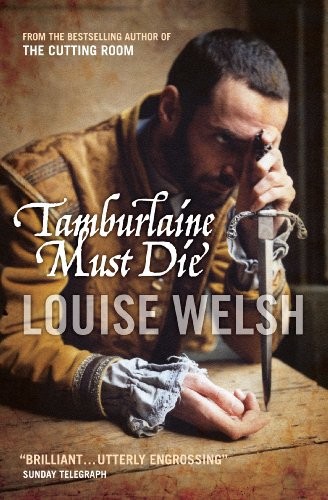

Tamburlaine Must Die

Tamburlaine

Must Die by Louise Welsh. Book Jacket.

1593

and London is a city on edge. Under threat from plague and war, its a

desperate place where strangers are unwelcome and severed heads grin

from spikes on Tower Bridge.

Playwright,

poet, and spy, Christopher Marlowe has three days to live. Three days

in which he confronts dangerous government factions, double agents,

necromancy, betrayal and revenge in his search for the murderous

Tamburlaine, a killer who has escaped from between the pages of his

most violent play…

Tamburlaine

Must Die is the swashbuckling adventure story of a man who dares to

defy both God and State and discovers that there are worse fates than

damnation.

Louise

Welsh has published a wide range of short stories and articles. Her

debut novel The Cutting Room was a bestseller in the UK and has

already sold into sixteen languages. She was chosen as one of

Britains Best First Novelists of 2002 by the Guardian and won the

Saltire First Book of the Year award and The Crime Writers

Association Creasey Dagger for the best first crime novel. For

several years she worked as a dealer in second-hand, out-of-print and

antiquarian books. She lives in Glasgow.

TAMBURLAINE

MUST DIE

Louise

Welsh

CANONGATE

BOOKS

First

published in Great Britain in 2004 by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High

Street, Edinburgh EH1 He 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Copyright © Louise

Welsh, 2004 The moral right of the author has been asserted British

Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this

book is available on request from the British- Library The publisher

gratefully acknowledges subsidy from the Scottish Arts Council

Hardback ISBN 1 84195 532 9 Paperback ISBN 1 84195 600 7 Typeset in

Van Dijck 12.5/18 pt by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Polmont,

Stirlingshire Page Design by James Hutcheson Printed and bound by GGP

Media, Germany www.canongate.net

To

Karen and Best Boy Zack

What

is our life? A play of passion; Our mirth, the music of division;

Our

mother's wombs the tiring houses be, When we are dressed for this

short comedy. Heaven the judicious sharp spectator is,

That

sits and marks still who does act amiss; Our graves that hide us from

the searching sun Are like drawn curtains when the play is done. Thus

march we playing to our latest rest Only we die in earnest, that's no

jest. On the Life of Man, Sir Walter Raleigh Cut is the branch that

might have grown full straight. Doctor Faustus, Christopher Marlowe

LONDON

29TH MAY 1593 I have four candles and one evening in which to write

this account. Tomorrow I will lodge these papers with my last true

friend. If I survive the day, they will light our pipes. But should I

not return, he has instructions to secrete this chronicle where it

will lie undiscovered for a long span, in the hope that when these

pages are found, the age will be different and my words may be judged

by honest eyes.

Reader,

I cannot imagine what future you inhabit. Perhaps the world is a

changed place, where men are honest and war, want and jealousies all

vanquished. If so, you will wonder at the actions of the players in

this poor play of passion. But if you are men like us you may

understand, and if you are men like us you will learn nothing, though

I gift you the only lesson worth learning, that there is no better

prize than life. Whatever the future be, if you are reading this, you

read the words of a man who knew how to live and who died an

unnatural and unjust death. And what follows is the true record of

the circumstances leading to my assassination.

My

name is Christopher Marlowe, also known as Marle, Morley, Marly,

known as Kit, known as Xtopher, son of a Canterbury cobbler. They say

shoemakers' sons go barefoot. It wasn't so bad for us, but my father

had a fondness for style that stretched beyond his means and damaged

family fortunes. I inherited his tastes, but desired none of his

debt, so I have always been in need of money and have risked much

where other men might have scrupled.

I

was a clever child. My keenness was brought to the attention of a

local Knight who sponsored my early education. Years later he would

judge me on a murder charge, never meeting my eye though I knew he

recognized me well.

When

I was seventeen I persuaded an old Archbishop that my one desire was

to enter the Church. He granted me a scholarship to Cambridge

University where I was recruited into a strange shadow world, where I

was assured I could help my country while helping myself. So it

proved and when it seemed my degree might not be granted, due to

various absences and rumours which placed me where I shouldn't be,

the Queen's own Privy Council gave guarantees I had been on Her

business and must not suffer for doing Her good service.

Eventually

I moved to London as I always knew I would, and set the world of

theatre afire. Men left Massacre of Paris with their sword-hands

twitching. And when my Faustus was performed, some said Lucifer

himself attended, curious to see how he was rendered. Yes, it is no

vanity to say my plays were a triumph, and Christopher Marlowe so

famous they had heard of me in Hell. And so I made shift betwixt two

night-time realms and thought my life charmed.

I

am of an adventurous nature. I have often invited danger and have

even goaded men to violence for the sake of excitement. I like best

what lies beyond my reach, and admit to using friendship, State and

Church to my own ends. I acknowledge breaking God's laws and man's

with few regrets. But if I die tomorrow, I will go to my grave a

wronged man. Were this fate of my own doing, I would greet it not

gladly, but with a nod to virtue's victory. As it is, if I meet death

tomorrow I promise to face him cursing man and God.

My

story begins on the 19th of May, 1593. All of that month I had been

installed at Scadbury, the country house of my patron, Thomas

Walsingham. For reasons I will soon explain, it was after noon before

I woke, but when I drew back my shutters the day seemed new minted.

It was as if I had lighted in another land. A world riven with

sunlight. I stood by the window enjoying the lack of London's stink

as much as the freshness of the countryside, then repaired to my desk

where I worked like the finest of scholars, until the sun edged half

the sky and a shadow crept across my words. I let the ink of my last

poetry sink into the page and when all danger of smudging was past,

locked the manuscript safe in my trunk, slipping one of my own hairs

into the clasp, an old precaution, done more from habit than

necessity.

It

had become my custom to walk in the forest in the early evening. As I

write, I search my remembrance, wondering if the weeks cloistered in

the country, avoiding the Plague which once more threatened the City,

had made me restless. I was used after all to the bustle of

theatrical life, London's stews, the half-world of ambidextors and

agents. But it seems when I look back on this walk at the end of a

perfect day, that it was the most untroubled hour of my life. I

didn't know that every step I took was echoed by the beat of a

messenger's horse speeding along the London road towards Scadbury. My

fate galloping to meet me.

I

had much to muse on that late afternoon. The events of the previous

night should have been prime in my mind. But I thought of nothing as

I walked through the forest. That is, I thought of nothing in

particular. Pleasant images threaded through my daydreams: the verses

I was engaged on; what might be served for supper; the thighs of a

woman I had lain with last winter; the dedication I would compose for

Walsingham; how perfect clusters of purple violets looked snug

against the forest floor; whether a doublet of the same shade might

suit me well: All mingled with contentment at the good fortune of my

state. The assurance of my patron's affection, the vigour of my

blood, the good reception I felt sure would greet my poetry when I

returned at last to London. I see now there was a complacence in my

satisfaction and, were I prone to superstition, might suspect I

invoked misfortune by displeasing God with my conceit. But such

thoughts are nonsense. When making mischief, man needs no help from

God or the Devil.

The

sun slipped lower beyond the canopy of leaves. The forest's green

light deepened, tree shadows lengthened, intersecting my path like

criss-crossing staves. I registered dusk's approach and walked

through bars of light and dark wondering if I might employ them as a

metaphor.

Nature

hath no distinction twixt sun and shadow, good and evil. I saw no

one, but the forest was secretly as busy as any London street. Night

and daytime creatures crossed, invisible in the gloaming. Birds

whistled territorial tunes and small beasts, newly awakened for the

night kill, rustled beneath fallen leaves, fleeing my approach.

Crickets scratched out their wash-board song and the wind whipped the

treetops into a roar. But any crowd has its silent watchers and once

I glimpsed the feminine form of a deer, trembling at the edge of my

vision.

`That's

right,' I said out loud, `never let your guard down.' Then laughed,

because I had let my own guard down, walking unaccompanied through

these woods on the verge of night. I remember I paused to light my

pipe, trusting the smoke to repel the swarms of midges that hovered

around my head, then strode on confident I could reach the house

before dark.

So

passed my last untroubled moments. I didn't see the man ride

uninvited into the courtyard, hear the familiar clatter of hooves

against cobbles, nor witness the manic roll in the eye or the sweat

on the flank of the horse driven too fast. But I returned in time to

register the customary pomposity of the Queen's Messenger, who

greeted me with sarcastic civility and an order from the Privy

Council for Christopher Marlowe, playwright, to return to London

immediately.

Does

each escape increase or decrease a man's chances? Each time he

wrestles free or weasels beyond charges, does he advance his

expertise or merely shrink the portion of his luck?

That

I had previously appeared before courts and councils and escaped with

only a month or two's incarceration was scant solace as I jolted

towards London on a borrowed horse, under arrest again. I recalled a

middle-aged swordsman I had once seen confronted with a duel outside

a Shoreditch tavern. The man had a reputation as a sword-sharp, but

when the bout began, he was ill-equipped to parry what he had once

dodged with ease. His opponent's blade had found its mark and the

hero of a hundred bouts had folded with a groan, that was more

surprise than pain. His killer shouted in triumph. But I knew then

that champions' lives are often short and the thought returned now to

snatch any comfort previous perils might have granted.

Walsingham

had sent ahead to the city to check the messenger's credentials. It

had been confirmed he was no conycatcher come to diddle me with a

false fine or useless bribe, but the genuine article sent direct from

the Privy Council, the most powerful men in the country. Men that can

sentence you to death or torture, or to wait your life away,

anticipating charges that never arrive. A league who answer only to

God, the Queen and each other.

Perhaps

it was the rhythm of the horse that turned my mind towards the events

of the previous night. But then I have found fear often inspires

thoughts of love, and if not love, then lust.

My

patron Lord Walsingham is magnificent, well set in every way.

Strong-boned and evenfeatured, his ancestry shows in the ease of his

walk, the readiness of his laugh. He ruled our dinner conversations

with a charm that belied the steel in his eye. I remembered the other

Walsingham, his cousin the spymaster, spider at the centre of a web

of intrigue, and watched my words lest my patron, had inherited the

old man's craft.

We

had lived well at Scadbury. I had grown used to fine wines and august

company and knew I would be loth to return to the poet's life when my

time there was done. The night before my arrest Walsingham and I had

dined alone but the table was set for a feast. Spiced capons boiled

with oranges, roast lamb and conies, a dish of larks and a salad of

cabbage lettuce and rosemary. I didn't mark the composition of the

leaves that evening, but reflect now that a maid well versed in the

language of flowers would have noted them and realised what was to

follow.