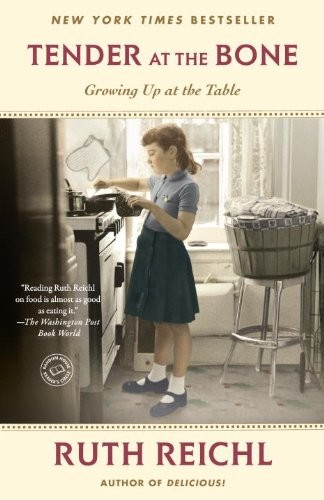

Tender at the Bone

Read Tender at the Bone Online

Authors: Ruth Reichl

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Cooking, #General

ALSO BY RUTH REICHL

Comfort Me with Apples: More Adventures at the Table

Not Becoming My Mother: And Other Things She

Taught Me Along the Way

Garlic and Sapphires: The Secret Life of a Critic in Disguise

For Michael

CONTENTS

2.

Grandmothers

3.

Mrs. Peavey

4.

Mars

5.

Devil’s Food

6.

The Tart

7.

Serafina

9.

The Philosopher of the Table

10.

Tunis

11.

Love Story

13.

Paradise Loft

14.

Berkeley

15.

The Swallow

16.

Another Party

17.

Keep Tasting

18.

The Bridge

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The good stories, of course, were repeated endlessly until they took on a life of their own. One of the stories I grew up on was a family legend about myself. Its point was to demonstrate my extraordinary maturity, even at the age of two. This is how my father told it:

“One Sunday in early fall we were sitting in our house in the country admiring the leaves outside the picture window. Suddenly the telephone rang: it was Miriam’s mother in Cleveland, saying that her father was gravely ill. She had to go immediately, leaving me alone with Ruthie, who was to start nursery school the next day.

“I, of course, had to be in the office Monday morning. Worse, I had an appointment I could not cancel; I simply had to catch the 7:07 to New York. But the school didn’t open until eight, and although I phoned and phoned, I was unable to reach any of the teachers. I just didn’t know what to do.

“In the end, I did the only thing I could think of. At seven I took Ruthie to the school, sat her on a swing outside and told her to tell the teachers when they came that she was Ruthie Reichl and she had come to go to school. She sat there, waving bravely as I drove off. I knew she’d be fine; even then she was very responsible.” He always ended by smiling proudly in my direction.

Nobody ever challenged this story. I certainly didn’t. It was not until I had a child of my own that I realized that nobody, not even my father, would leave a two-year-old alone on a swing in a strange place for an hour. Did he exaggerate my age? The length of time? Both? By then my father was no longer available for questions, but I am sure that if he had been he would have insisted that the story was true. For him it was.

This book is absolutely in the family tradition. Everything here is true, but it may not be entirely factual. In some cases I have compressed events; in others I have made two people into one. I have occasionally embroidered.

I learned early that the most important thing in life is a good story.

THE QUEEN OF MOLD

This is a true story.

This is a true story.

Imagine a New York City apartment at six in the morning. It is a modest apartment in Greenwich Village. Coffee is bubbling in an electric percolator. On the table is a basket of rye bread, an entire coffee cake, a few cheeses, a platter of cold cuts. My mother has been making breakfast—a major meal in our house, one where we sit down to fresh orange juice every morning, clink our glasses as if they held wine, and toast each other with “Cheerio. Have a nice day.”

Right now she is the only one awake, but she is getting impatient for the day to begin and she cranks WQXR up a little louder on the radio, hoping that the noise will rouse everyone else. But Dad and I are good sleepers, and when the sounds of martial music have no effect she barges into the bedroom and shakes my father awake.

“Darling,” she says, “I need you. Get up and come into the kitchen.”

My father, a sweet and accommodating person, shuffles sleepily down the hall. He is wearing loose pajamas, and the strand of hair he combs over his bald spot stands straight up. He leans against the sink, holding on to it a little, and obediently opens his mouth when my mother says, “Try this.”

Later, when he told the story, he attempted to convey the awfulness of what she had given him. The first time he said that it tasted like cat toes and rotted barley, but over the years the description got better. Two years later it had turned into pigs’ snouts and mud and five years later he had refined the flavor into a mixture of antique anchovies and moldy chocolate.

Whatever it tasted like, he said it was the worst thing he had ever had in his mouth, so terrible that it was impossible to swallow, so terrible that he leaned over and spit it into the sink and then grabbed the coffeepot, put the spout into his mouth, and tried to eradicate the flavor.

My mother stood there watching all this. When my father finally put the coffeepot down she smiled and said, “Just as I thought. Spoiled!”

And then she threw the mess into the garbage can and sat down to drink her orange juice.

For the longest time I thought I had made this story up. But my brother insists that my father told it often, and with a certain amount of pride. As far as I know, my mother was never embarrassed by the telling, never even knew that she should have been. It was just the way she was.

Which was taste-blind and unafraid of rot. “Oh, it’s just a little mold,” I can remember her saying on the many occasions she scraped the fuzzy blue stuff off some concoction before serving what was left for dinner. She had an iron stomach and was incapable of understanding that other people did not.

This taught me many things. The first was that food could be dangerous, especially to those who loved it. I took this very seriously. My parents entertained a great deal, and before I was ten I had appointed myself guardian of the guests. My mission was to keep Mom from killing anybody who came to dinner.

Her friends seemed surprisingly unaware that they took their lives in their hands each time they ate with us. They chalked their ailments up to the weather, the flu, or one of my mother’s more unusual dishes. “No more sea urchins for me,” I imagined Burt Langner saying to his wife, Ruth, after a dinner at our house, “they just don’t agree with me.” Little did he know that it was not the sea urchins that had made him ill, but that bargain beef my mother had found so irresistible.

“I can make a meal out of anything,” Mom told her friends proudly. She liked to brag about “Everything Stew,” a dish invented while she was concocting a casserole out of a two-week-old turkey carcass. (The very fact that my mother confessed to cooking with two-week-old turkey says a lot about her.) She put the turkey and a half can of mushroom soup into the pot. Then she began rummaging around in the refrigerator. She found some leftover broccoli and added that. A few carrots went in, and then a half carton of sour cream. In a hurry, as usual, she added green beans and cranberry sauce. And then, somehow, half an apple pie slipped into the dish. Mom looked momentarily horrified. Then she shrugged and said, “Who knows? Maybe it will be good.” And she began throwing everything in the refrigerator in along with it—leftover pâté, some cheese ends, a few squishy tomatoes.

That night I set up camp in the dining room. I was particularly worried about the big eaters, and I stared at my favorite people as they approached the buffet, willing them away from the casserole. I actually stood directly in front of Burt Langner so he couldn’t reach the turkey disaster. I loved him, and I knew that he loved food.

Unknowingly I had started sorting people by their tastes. Like a hearing child born to deaf parents, I was shaped by my mother’s handicap, discovering that food could be a way of making sense of the world.

At first I paid attention only to taste, storing away the knowledge that my father preferred salt to sugar and my mother had a sweet tooth. Later I also began to note how people ate, and where. My brother liked fancy food in fine surroundings, my father only cared about the company, and Mom would eat anything so long as the location was exotic. I was slowly discovering that if you watched people as they ate, you could find out who they were.

Then I began listening to the way people talked about food, looking for clues to their personalities. “What is she really saying?” I asked myself when Mom bragged about the invention of her famous corned beef ham.

“I was giving a party,” she’d begin, “and as usual I left everything for the last minute.” Here she’d look at her audience, laughing softly at herself. “I asked Ernst to do the shopping, but you know how absentminded he is! Instead of picking up a ham he brought me corned beef.” She’d look pointedly at Dad, who would look properly sheepish.

“What could I do?” Mom asked. “I had people coming in a couple of hours. I had no choice. I simply pretended it was a ham.” With that Dad would look admiringly at my mother, pick up his carving knife, and start serving the masterpiece.

MIRIAM REICHL’S

CORNED BEEF HAM

4 pounds whole corned beef

5 bay leaves

1 onion, chopped

1 tablespoon prepared mustard

¼ cup brown sugar

Whole cloves

1 can (1 pound 15 ounces) spiced peaches

Cover corned beef with water in a large pot. Add bay leaves and onion. Cook over medium heat about 3 hours, until meat is very tender

.

While meat is cooking, mix mustard and brown sugar

.

Preheat oven to 325°

.

Take meat from water and remove all visible fat. Insert cloves into meat as if it were ham. Cover the meat with the mustard mixture and bake 1 hour, basting frequently with the peach syrup

.

Surround meat with spiced peaches and serve

.

Serves 6

.

Most mornings I got out of bed and went to the refrigerator to see how my mother was feeling. You could tell instantly just by opening the door. One day in 1960 I found a whole suckling pig staring at me. I jumped back and slammed the door, hard. Then I opened it again. I’d never seen a whole animal in our refrigerator before; even the chickens came in parts. He was surrounded by tiny crab apples

Most mornings I got out of bed and went to the refrigerator to see how my mother was feeling. You could tell instantly just by opening the door. One day in 1960 I found a whole suckling pig staring at me. I jumped back and slammed the door, hard. Then I opened it again. I’d never seen a whole animal in our refrigerator before; even the chickens came in parts. He was surrounded by tiny crab apples

(“lady apples”

my mother corrected me later), and a whole wreath of weird vegetables.