Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (2 page)

Read Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh Online

Authors: John Lahr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary

BOOK: Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh

6.42Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Dowling met “a sick, tormented boy” profoundly wary of Broadway and those swamis of box-office wisdom, “the Broadway crowd.” “He couldn’t believe. He sat and watched. He’d been through the wringer so much. I don’t think he even heard half of what I was talking about,” Dowling recalled. “He was far away. He was arriving at a decision within himself.” “He said, ‘Do you really mean that this will go into a Broadway theatre?’ I said, ‘Well, I wouldn’t be wasting your time or my own, and I wouldn’t be spending this money if I didn’t think so. The Broadway theatre is the only theatre I know.’ Without much ado, he left, not too excited. He didn’t say much of anything.”

“Success is like a shy mouse—he won’t come out while you’re watching,” Williams had written; he certainly didn’t see

The Glass Menagerie

’s potential. Dismissing it as “a nauseous thing” and “an act of

compulsion

not love,” he scrawled his displeasure on the title pages of the various drafts: “a rather tiresome play,” “the ruins of a play,” “a lyric play,” and, on the final submitted manuscript, “a gentle play.” To this last comment Williams appended a note: “The purposes of this play are very modest. The hurdles are lowered to give the awkward runner an exercise in grace and lightness of movement. No stronger effect is called for than that evoked by a light but tender poem.”

The Glass Menagerie

’s potential. Dismissing it as “a nauseous thing” and “an act of

compulsion

not love,” he scrawled his displeasure on the title pages of the various drafts: “a rather tiresome play,” “the ruins of a play,” “a lyric play,” and, on the final submitted manuscript, “a gentle play.” To this last comment Williams appended a note: “The purposes of this play are very modest. The hurdles are lowered to give the awkward runner an exercise in grace and lightness of movement. No stronger effect is called for than that evoked by a light but tender poem.”

But the cloud that seemed to hang over Williams’s view of the play didn’t obscure its shine for Dowling. He broke his contract for

The Passionate Congressman

. “I gave up a sure $25,000 to do it, and I didn’t have twenty-five cents when I did it. I was always just ahead of the sheriff,” he said. The producers were furious, but Dowling’s enthusiasm for his new property was so infectious that he persuaded one of them, Louis Singer, to put up $50,000 without ever having read it. The no-read condition was only part of the tough deal Dowling cut with Singer, who balked at first. “I said, ‘Make up your mind.’ He hesitated, and I thought I was going to lose him,” Dowling recalled. “I said, ‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do. You know what the usual deal is on the Street. The money gets 50% and the producer gets 50%, but the money gets their investment back before the other fellow gets a cent and then they divide dollar for dollar.’ He said, ‘That’s right. Is that what you’re proposing?’ I said, ‘No. That’s the deal you’ve got now. You bring in an agreement where you’re not to read the play, you’re not to attend any rehearsals, you’re not to have anything to do with this. You keep completely away, until we’re getting ready to open, and until everything is paid for and all the bills are up. If you do this, I’ll give you an extra 25%. You get 75% and I get 25%.’ And that was the deal.”

The Passionate Congressman

. “I gave up a sure $25,000 to do it, and I didn’t have twenty-five cents when I did it. I was always just ahead of the sheriff,” he said. The producers were furious, but Dowling’s enthusiasm for his new property was so infectious that he persuaded one of them, Louis Singer, to put up $50,000 without ever having read it. The no-read condition was only part of the tough deal Dowling cut with Singer, who balked at first. “I said, ‘Make up your mind.’ He hesitated, and I thought I was going to lose him,” Dowling recalled. “I said, ‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do. You know what the usual deal is on the Street. The money gets 50% and the producer gets 50%, but the money gets their investment back before the other fellow gets a cent and then they divide dollar for dollar.’ He said, ‘That’s right. Is that what you’re proposing?’ I said, ‘No. That’s the deal you’ve got now. You bring in an agreement where you’re not to read the play, you’re not to attend any rehearsals, you’re not to have anything to do with this. You keep completely away, until we’re getting ready to open, and until everything is paid for and all the bills are up. If you do this, I’ll give you an extra 25%. You get 75% and I get 25%.’ And that was the deal.”

Dowling could turn his attention now to casting the four-hander, whose biggest challenge was Amanda Wingfield, the embattled bundle of Southern decorum and Puritan denial. At the suggestion of George Jean Nathan, an influential critic and the model of the waspish Addison DeWitt in the film

All About Eve

, Dowling went to see Laurette Taylor, who lived above the Copacabana at the top of Hotel 14 on East Sixtieth Street, where, as Dowling said, “she’d been hibernating with a gin bottle for twelve years.” “She was a long time allowing me up,” Dowling recalled. When she opened the door, the sight of her frightened him. “She was in her bare feet, with an old beaten[-up] kimono around her, and her hair all scraggly. It was a pitiful kind of thing,” he said. He gave her the pitch and the play. “Is your telephone on here?” Taylor asked, and shut the door.

All About Eve

, Dowling went to see Laurette Taylor, who lived above the Copacabana at the top of Hotel 14 on East Sixtieth Street, where, as Dowling said, “she’d been hibernating with a gin bottle for twelve years.” “She was a long time allowing me up,” Dowling recalled. When she opened the door, the sight of her frightened him. “She was in her bare feet, with an old beaten[-up] kimono around her, and her hair all scraggly. It was a pitiful kind of thing,” he said. He gave her the pitch and the play. “Is your telephone on here?” Taylor asked, and shut the door.

Eddie Dowling as the Narrator in

The Glass Menagerie

The Glass Menagerie

Not acting had left Taylor in a “jam about money.” To keep going and to keep her brain from ossifying in the loneliness of her handsome apartment, Taylor wrote short stories and articles for

Vogue

and

Town and Country

. She also completed a novel, which she tried, unsuccessfully, to sell to the movies. But “no play has come my way all winter, which is indeed very discouraging,” she wrote to her son. “I am, of course, desperately let down in my courage for a bit and certainly let down in my finances.”

Vogue

and

Town and Country

. She also completed a novel, which she tried, unsuccessfully, to sell to the movies. But “no play has come my way all winter, which is indeed very discouraging,” she wrote to her son. “I am, of course, desperately let down in my courage for a bit and certainly let down in my finances.”

Taylor immediately sat down to read the play. “Between two and three in the morning, after I finished reading ‘The Glass Menagerie’, I thought a lot about the mother in the story,” Taylor said later. In Amanda Wingfield’s misguided endurance, Taylor recognized both the comedy and the tragedy of a grief that she herself was still living through. “I could look back and see her as a girl. Pretty, but not very intelligent, with plenty of beaux. Not seventeen of them, of course. She says seventeen in the play, but she’s lying. I know why her husband left her. She talked and talked until he couldn’t stand it. She nags her children to pull them out of their poverty. She loves them. For them, she has strength and tenacity.” During the war years, Taylor had been sent scripts with only “tobacco-spitting mammas, horrible old harridans—crude disgusting roles,” as she put it. Now, she knew that “the absolutely right part had come along.”

The next day, Taylor called Dowling and asked him back up to her apartment. Taylor met him at the door with the play under her arm. “She’d spruced up a little bit,” Dowling recalled. “Do you think Broadway, this bastardly place, will buy this lovely, delicate fragile little thing?” Taylor asked. “This is what I’m betting on,” Dowling replied. “That’s the kind of talk I like to hear,” Taylor said, adding “but you can’t get a theatre with me.” Dowling pooh-poohed Taylor’s worry and told her that was his concern. “Can we talk business. Can you tell me what you want?” Dowling said.

“Right this minute? You know what I’d like better than anything else in the world? I’d like a martini,” Taylor replied.

“Would you like me to take you out and get you a martini?” Dowling said.

Taylor did a little twirl around the room and lifted her leg. “She said, ‘I can’t go out. Look,’ ” Dowling recalled. “She said, ‘Look at those nylon stockings. There’s a war on, you know that. I don’t have a pair of stockings to my name.’ I said, ‘I could order some things for you.’ ” Taylor continued, “You’re a big shot, head of the USO [United Service Organizations]. You have a lot of influence. Could you get me a few pairs of nylon stockings?”

“I can get you all the stockings you want. I have to get them for the troupes we send abroad. I’ll get them for you today,” Dowling said.

“All right,” Taylor said. “You’ve got your actress. I’ll play that Southerner.”

Dowling was thrilled to have his star; but Tennessee Williams, after hearing her first tentative reading at Hotel 14, was not. When he and Dowling got outside, Dowling remembered, Williams stood beside a row of garbage cans, beseeching him, “Oh, Mr. Dowling, you’ve got to get rid of that woman who’s doin’ a Negress. My mother ain’t a Negress. My mother’s a lady.” “Young man,” Dowling told him. “You’ll live to eat those words.” He went on: “You wait till the curtain goes up on it. You just wait.”

ON DECEMBER 16, 1944, the day the company was to catch the train to Chicago, where the play was trying out, Williams almost didn’t make it to Grand Central. The night before, he’d gone on the town with Dowling, Louis Singer, George Jean Nathan, and Nathan’s girlfriend, Julie Haydon, who played Laura Wingfield, Amanda’s daughter. Margo Jones, whom Williams called “the Texas Tornado” and whom he had lobbied to be the play’s co-director, an agreement that rankled Dowling, who referred to her as “my assistant,” also joined the party. They were having seasonal drinks at a French café when Dowling proposed a toast to Williams. “Wouldn’t it be great, George, a fine Christmas present, if the curtain went up and the next day the Chicago papers gave our boy a hit?” Dowling said. “Just a minute before you drink that toast,” Nathan cut in. “You’re asking a whole lot, Dowling. I don’t think there’s going to be anything like that unless this young man takes out a lot of the delicatessen that’s in there. I know it’s still stunk up with a lot of Limburger he’s got to get out of there. If he doesn’t, you’ll be back before New Year’s, and we’ll have a New Year’s drink at the Algonquin.”

With that, Nathan told Haydon to get her things, and got up to leave. “As Tiny Tim said,” he remarked to the assembled. “Bless you merry gentlemen, let nothing you dismay, even the wisdom of the acidulous Nathan.” The famous critic was hardly out the door before Singer started to cry. “I knew it. I knew it,” he sobbed. “What did you know?” Dowling said. “Ilka Chase told me. Laurence Stallings told me. The president of City College, my dear friend. A lot of my broker friends. They all told me what a silly ass I was to put up all this money. I don’t want to go to Chicago. I knew everything that Mr. Nathan said.” “Oh, you did? How did you find this out?” Dowling challenged him. “You left a copy of the play on the desk one day and I read it,” Singer replied.

Williams was stung by the scene, but most of all by Nathan. “He doesn’t mean to hurt you,” Dowling told him later in the night. “Don’t think that he dislikes you or that there’s anything personal about this. . . . He’s disappointed in me that I haven’t had more influence with you.” Dowling added: “Go home and don’t try to sleep. Take a bottle of gin home with you. Have a damn good night. Stagger onto the train, but get on it and come out there.” Williams didn’t say whether he would or wouldn’t be on the train. But later, after he’d left, Margo Jones took Dowling’s arm. “Thank you, Eddie. He’ll be on the train,” she said. And the next morning, he was.

Setting off for Chicago, Williams didn’t know what to expect. “It’s just in the lap of the gods,” he wrote to his friend the publisher James Laughlin, whom he frequently addressed as “Jay.” “Too many incalculables—the brain-cells of an old woman, a cold-blooded banker’s reckoning of chances, enigmas of audiences and critics. It is really a glass menagerie that we are taking on the road and God only knows how much of it will survive the journey.”

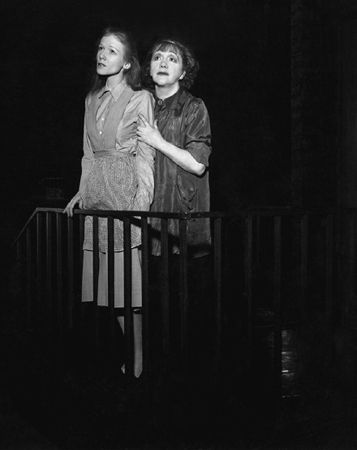

Julie Haydon and Laurette Taylor as Laura and Amanda in

The Glass Menagerie

The Glass Menagerie

The troupe had a mere fifteen days in Chicago to get their show to opening night. “Well, it looks bad, baby,” Williams noted in his diary after an early rehearsal. In the narrow, carpeted Chicago rehearsal hall, Williams was perplexed by Taylor’s flat, ungiving performance and her ad-libbing. “My God, what corn!” Williams screamed over the footlights after Taylor “made one of her little insertions.” Williams wrote Windham about the encounter. “She screamed back that I was a fool and all playwrights made her sick that she had not only been a star for forty years, but had made a living as a writer which was better than I had done.”

“What was she working toward in that terrifyingly quiet and hidden laboratory of her work in progress?” he wrote, several years later, recalling his mounting despair at her muted presentation. “There she sat, a small round woman with amazingly bright eyes usually shielded by a wide-crowned hat that came down level with her eyebrows. I say ‘sat’ advisedly for she did not often rise to her feet and when she did, she made such indefinite, shuffling movements that you wondered if she realized she was actually standing up! What was she thinking? What was she doing? What was going on? Only the eyes seemed much alive to the progress of rehearsals. How they darted and shone as if they possessed some brilliant life of their own! Watching inwardly, outwardly! But what? And the speech—God help us! She usually seemed to have difficulty forming words with her tongue and sometimes the words were indistinguishable, they were only vague mutterings. . . . Sometimes she would not bother to get to her feet and perform a cross in the playing area. Rather she would mention it verbally. ‘Now I get up,’ she would say, ‘and I go over there.’ She would point a bit indefinitely, sometimes more at the ceiling than the floor, and you wondered if she intended to walk up the side of a flat like a human fly. ‘When I get over there,’ she would continue, hesitantly, ‘I open my pocketbook and take out a handkerchief and sniff a little. No, I don’t,’ she would suddenly amend. ‘I sit right there like I’m sitting and I don’t do a thing!’ And she would look up with blazing eyes at this heaven-sent inspiration, not at all troubled by the blank look that she got from the rest of us in the dim room. I was keeping a journal at the time. I don’t have it with me but I can quote from memory this line. ‘Poor Laurette! She mumbles and fumbles! Seems hopelessly lost!’ ”

Other books

The Lost Girl (Brennan and Esposito) by Tania Carver

Snapshot by Angie Stanton

Calligraphy Lesson by Mikhail Shishkin

Night in Eden by Candice Proctor

Grail of Stars by Katherine Roberts

The Abyssinian Proof by Jenny White

Needing Harte (1-800-DOM-Help) by Marilu Mann

Guardian of Lies by Steve Martini

God Don't Like Haters 2 by Jordan Belcher