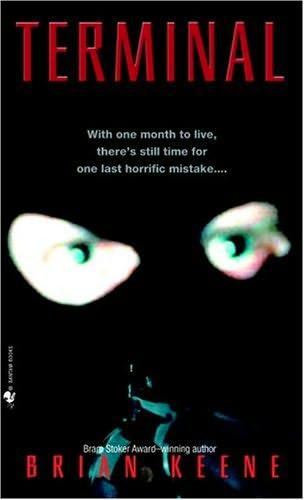

Terminal

For Geoff Cooper, Michael T. Huyck Jr., and Michael Oliveri.

We are ka-tet. All for one and one for all . . .

To many men life is a failure

A poison worm gnawing at their heart

Then let them see to it

That their dying is all the more a success

— FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

Thus Spake Zarathustra

Rejoice, young man, in thy youth

But know that God will bring thee

Into judgment

— ECCLESIASTES 11:9

“I’m going to kill the bastard!”

— BABY FACE NELSON TO JOHN DILLINGER

“Forget it and grab the money!”

— JOHN DILLINGER TO BABY FACE NELSON

Farewell happy fields

Where joy forever dwells

Hail horrors, hail . . .

— JOHN MILTON

Paradise Lost

Thanks to Cassandra; Sam, who came along at just the right time; Anne Groell for the French Sushi; Josh Pasternak; Rich SanFilippo, for the bat and the murder ballads; Ed Gorman; Larry Roberts; Alan M. Clark; Duane Swierczynski, my partner in crime; Cullen Bunn; Judi Rohrig; Officer Tom O’Brien (no relation to the main character); Maria Cotto, for the swearing lessons; Carl, for help with the drugs; Matt Warner (drop and give me 1,000); Gina Mitchell; Mark Lancaster, for once again being my eyes and ears; Adam Pepper, who read this on the back of scrap paper; John Urbancik, for reading this during the carnival instead of going to Heaven by answering three easy questions; and finally, to the memory of the foundry sage Robert Fitro, whose wisdom is not forgotten.

Author’s Note: Though Hanover, York, and many of the locat ions in this novel are real, I have taken fictional liberties with them. If you live there, don’t look for your bank. You probably won’t find it.

Life’s a bitch, then you die. That’s my philosophy in a nutshell, and it was reinforced that morning.

“Mr. O’Brien, perhaps you’d better sit down.”

That didn’t sound good. Neither did the fact that we were doing this in his office, instead of the examination room.

I shrugged. “It’s okay. I can stand.”

A fancy degree in an expensive-looking frame hung on the wall. I focused on it, wondering how much it cost him to go to medical school. How much money did he make? I bet it was more than I made working at the foundry.

He cleared his throat, glanced down at the desk, and looked back up at me.

“Mr. O’Brien—”

Here it comes. My cholesterol is too high. I need to quit smoking and drinking and eating rare steaks and baked potatoes with a shitload of butter and sour cream or I’ll be dead before I’m thirty.

“— you have cancer.”

I said nothing. I couldn’t say anything, even if I’d known what to say. There was a big lump in my throat, and it grew as he continued. My ears felt hot and began to ring. Something moved around deep down inside my stomach, a sloshing that made me queasy and afraid at the same time. The doctor seemed to shrink and swell in front of my eyes, and his voice echoed around the office. Everything started to spin and my head grew light, like I’d stood up too quick or something.

“I’ve conferred with several associates of mine, all of who specialize in this. The diagnosis is certain. The cancer is spreading throughout your throat, particularly the esophagus, as well as your jaw, chest, and lungs. It’s gotten into your lymph nodes. Those are the lumps beneath your armpits. Worse, the disease is spreading at an alarming rate. It’s what we term Grade Four— extremely serious and very, very aggressive.”

I stared at him, then decided to sit down after all. If I hadn’t, I think I would have collapsed. My legs felt like spaghetti. Outside, I heard the clackety-clack-clack as the receptionist banged away on her keyboard. The keys seemed very loud in the silence.

“Cancer. Well shit.”

“Yes.”

“That ain’t good.”

“No.”

He folded his hands, sighed, and waited for me to speak.

I was having trouble doing that. Fear kicked in, thrumming in my gut like a subwoofer.

“So— am I going to have to get one of those holes in my neck? You know, those tracheotomy things? A voice box like that guy Ned on South Park?”

“Mr. O’Brien. Tommy. I know this is a shock, but I need to make sure that you understand.”

He removed his glasses, rubbed his forehead, and sighed again. Then he put the glasses back on, folded his hands neatly on the desk, and looked at me. I knew that look. It was a look that said I’m not fucking around here.

“Your cancer is at a very advanced stage. At this point, chemotherapy and treatment on the throat lesions would be ineffective, as would removal of the tumors and steroid therapy. Truthfully, I’d be hesitant even to do an exploratory on the growths at this point. As I said, a Grade Four tumor is very aggressive, and you have multiples. Literally dozens, in fact. To be honest, I’ve never seen so many in a patient before. I’m afraid the outlook is terminal. I am truly, truly sorry, Tommy. You have my deepest regrets. Had we caught it earlier—” He shrugged and found something to look at on his blotter.

“Shit,” I said again. “Terminal. Huh.” It felt like somebody had hit me in the stomach.

After a few moments, the doctor stirred.

“I don’t understand, Tommy. Why didn’t you come in earlier, at the first sign?”

“I don’t have any health insurance, Doc. The foundry keeps us below thirty-five hours a week so they don’t have to pay for it. State law, you know? And my wife only works part-time at the Minit-Mart over on Eisenhower and Carlisle Street. She doesn’t have any insurance either.”

The doctor nodded and fell silent again.

“Can’t you cut them out? The tumors?”

“It would be futile, Tommy. The success rate is very low and the surgery is quite invasive. The cancer has spread rather quickly, expanding into the rest of your body. Your esophagus is— not good. The tumors in your jaw have sent tendrils into your brain, like roots, if that helps you to understand it better. That’s where the headaches are coming from. Several of the growths have fused with your spine. There is simply no way that we could remove them all, and even if we did, you’d be horribly disfigured. We would literally have to remove your jaw and your nose. There are prosthetics for that, of course, but they are very costly.” He stared back down at the blotter, fiddling with a pen.

There was more, but I didn’t hear it. The doctor showed me pamphlets that I pretended to understand. Even though he already knew the answers, he asked again if I smoked (I did), drank (only a few days during the week, Friday night after work, and on the weekends), used drugs (once in a while, but only weed), worked near radiation (nope, just foundry dirt and molten iron), family history (my mother had breast cancer), or had a father who was exposed to Agent Orange in Vietnam (my father was in ’Nam but came back as an alcoholic). He nodded as I confirmed each one.

The doctor offered me some medication to make the nausea and pain easier, wrote a prescription for something (but I wasn’t paying attention and didn’t really understand what it was for), and asked me to come back in a couple days so we could discuss arrangements.

“What kind of arrangements? What’s there to discuss?”

He explained the difference between a hospital stay and a hospice, and told me that I’d have to make some tough decisions. He’d be there to help me with them.

“Is that appointment going to cost money? ’Cause I don’t get paid again for another two weeks.”

“Well”— he seemed taken aback—“I’m sure we can arrange something, Mr. O’Brien.”

I was Mr. O’Brien again, soon as he saw that he wasn’t getting thirty bucks right away for another office visit.

“I know all about the difference between hospitals and hospices, Doc. Hospitals just fuck you in the ass. Hospices try to make you comfortable first, then they fuck you in the ass.”

“Mr. O’Brien—”

“Just tell me how long.”

“Tommy—”

“How long, goddamn it?”

Outside, the receptionist stopped typing. The office was very quiet, so quiet I could hear my heart beat, pounding like a bass line in my favorite Snoop Dog song.

“Well, it’s hard to be certain of course, Mr. O’Brien, but I’d say you have approximately one month to live. Certainly no longer than three.”

That was it. He showed me to the door.

Outside, the sun was shining, and it felt good on my face. I could smell the honeysuckle growing alongside the building. A bird hopped across the parking lot in front of me. Several more chirped and sang to each other in the trees. A gnat, the first one I’d seen this spring, buzzed my ear. I resisted the urge to squash him, letting him live instead, so that he could fly away and bother someone else.

Winter had come and gone, and now it was spring. The season of renewal. That magical time of year when Mother Nature takes her clothes off, puts on a thong bikini, and shouts: “Let’s party!”

Everything was coming to life while I was dying.

I was terminal.

That was when my knees gave out, and everything got dark.

* * *

I don’t know how long I lay there. A minute maybe, but it seemed like more. Nobody noticed, so it couldn’t have been that long. I skinned my hand on the pavement, and wiped the blood on my baggy jeans.

The truck didn’t want to start right away. It coughed, the same way I’d been doing. I ended up having to pop the hood and hit the starter with a hammer. Then it turned over. The power button on my stereo was broken, so I’d wedged a toothpick in and taped it in place to keep the power on. As the engine sputtered and choked, the radio came on. Howard Stern was interviewing a midget. I thought about all the guys I’d heard call in to the Stern show over the years, dying of cancer and wanting him to fulfill their last wishes— usually to get laid by a porno star.

My wish was that this would all be a dream. It couldn’t have been real, could it? Maybe the doctor was wrong.

My hands started to shake, and everything began to spin again. Howard’s voice grew muffled, like it was coming down a long tunnel. I closed my eyes and took several deep breaths, waiting for it to pass.

I didn’t feel much like laughing, so I turned off Howard and put in Eminem’s The Eminem Show instead. The thudding bass made my headache worse. Eminem was rapping about dying tomorrow and wondering if the people left behind would feel love and show sorrow or if it would even matter.

I turned the stereo off and drove in silence.

There was no way I was going back to work, but I couldn’t go home yet either. My hands just wouldn’t stop shaking. I stopped at a gas station, bought a pack of cigarettes, and lit one up. I inhaled, savoring the smoke. The nicotine rushed through my veins and everything was okay after that. My hands quit shaking. The headache became dull. I was awake and alert. I felt alive.

Alive. For the time being, at least.

* * *

That was how it all started. Everything that came after— John and Sherm, Murphy’s Place, the plan, Wallace and his crew, the robbery, the standoff, the fucking bloodbath— all of it started with that trip to the doctor. I hadn’t even wanted to go. Michelle made me when the headaches got really bad. Maybe if I hadn’t gone, none of this would have ever happened.

But it did. All of it; the bank, the hostages, Sheila and Benjy.

Especially Benjy. Especially him . . .

That was how it started.

Let me have another cigarette, and I’ll tell you what happened next.

Like I said, I couldn’t go back to work at the foundry, but I couldn’t go home yet either. Michelle got off from the Minit-Mart at two, and by then, she’d have picked T. J. up at day care. They’d be waiting for me, and Michelle would have questions. Questions I wasn’t sure how I’d answer.

Instead of going back to our crib, I drove around town on autopilot— just aimlessly cruising the streets and back roads and alleys. I’d grown up here, lived here, and the way things looked, was going to die here, and I knew those roads forward and backward.

After a while, I experimented with the radio again. Pink was getting the party started. I turned it back off. Radio sucks these days, with the exception of Howard Stern. Pretty soon, I guess he’ll be gone too, and then I don’t know what the fuck people will listen to. I popped in Dr. Dre’s The Chronic instead. Perfect background music. I kept the volume low and turned the bass down so it wouldn’t make my head hurt more.

Eventually, I rolled by the trailer park where I grew up. The old trailer that I’d lived in with my parents was in pretty bad shape. The landlord was renting it to a group of migrant workers up from Mexico for the summer to pick apples at the orchard in Fawn Grove. There must have been twenty of them living there, and I couldn’t imagine how they all fit under that roof. It had been crowded when it was just the three of us, before Dad left.

I was born Thomas William O’Brien, but everybody called me Tommy. Everybody except for my old man, who didn’t call me much of anything, and my mom, who called me “asshole,” “little cock-sucker,” and “shit-for-brains.” I was white trash from white trash, and I admit it. Around here, you’ve got no choice. Everybody in this town is trash, and everyone is poor. The only difference is the color of their skin, what they drive, and whether they listen to metal, rap, or country music. If you live out in the suburbs, you’ve got a chance, but here in town it’s always the same story.

Hanover used to be a pretty happening place. But when the jobs started disappearing, it changed. First we lost the cigar factory, then the box plant, and even the recycling center. The shoe factory moved to Mexico and the paper mill relocated to North Carolina. Then the mall shut down after the big chain stores pulled out. Eventually, we were left with the foundry and not much else. If you were good at bending a wrench, you could get a job at one of the garages or dealerships. If you wanted to be a telemarketer, there were still a handful of those jobs available. But most people either had to commute out of town or stay here and work in the foundry or some other meaningless minimum-wage gig. Even commuting didn’t offer much hope these days. It seemed like the rest of the country was starting to get hit hard as well.

The town used to be alive. Now industrial ghosts haunted every street and corner. The skeletons of dead factories rusted where they stood, providing shelter for the homeless and the rats. The abandoned buildings were depressing and stank of hopelessness and despair.

They reminded me of my father. He’d stunk of the same things.

My old man was a horrible father. A drunk. He worked night shift at the foundry, then hit the bars that catered to third-shift drunks like him. He’d drink every morning from six till about noon, then he’d come home and smack my mom and me around until he went to sleep. Then he’d get back up and start the whole routine over again. I hated the bastard. My earliest memory is of me biting his leg to get his attention, and him kicking me across the kitchen floor. That pretty much set the tone for our relationship.

He died when I was seven. Skipped town with a waitress from the VFW, and two days later their car was hit by a train down in Westminster. Killed them both instantly. I remember thinking that something was wrong with me because I didn’t feel sad. There was no crying, and the people on Mom’s soap operas always cried when someone died. But I didn’t cry for him, not then and not since.

Mom didn’t work, so we lived on WIC stamps, government cheese (which makes the best grilled cheese sandwiches in the world) and the paychecks from her string of boyfriends. She dated truckers, mostly. Some of them were assholes. Some weren’t. I liked one guy in particular; we called him Swampy Pete because he was from Mississippi. He used to bring me comic books back from his long hauls across the country, and he taught me how to play baseball and how to fish. I was pissed off when Mom dumped him for a cement truck driver with no front teeth. I didn’t speak to her for a week, and to get back at her, I busted out our picture window with a baseball bat. She beat my ass for that one.

When I was sixteen, Mom got breast cancer. She died halfway through the treatments. But it wasn’t the cancer or the treatments that killed her. One of her boyfriends did. He caught her slow dancing at the bar with another man. He waited for her outside, and after last call, when she and her new friend came stumbling out, drunk off their asses and laughing it up, he shot them both. Mom got it in the stomach and didn’t die right away, so he shot her again. And again. And again. Then he killed himself. Sucked on a gunmetal dick and pulled the trigger as the cops surrounded him.

I cried that time. I cried a lot. After the funeral, I lived with my friend John and his parents until we graduated, since my grandparents were long dead and I didn’t have any aunts or uncles.

* * *

While I was lost in thought, the toothpick popped out of the stereo. I bent over, feeling around for it, and almost slammed into a telephone pole. It would have been ironic, dying like that. In a way, it would have been like what happened to my mother. But I swerved, found the toothpick, and jammed it back into place.

I drove by my old high school and stopped for a moment back behind the gym. I saw myself, sixteen and hanging out in that very spot, cutting class and smoking cigarettes and selling weed to the jocks and the National Honor Society kids. John used to chill there with me. We’d known each other since first grade, grown up together, gotten in trouble together. Now the two of us, along with our friend Sherm, worked together and drank together at Murphy’s Place on Friday nights.

Cancer. Terminal cancer. Growing at an alarming rate. One month to live, probably . . .

I was going to have to tell John. He would have to watch over Michelle and T. J. for me.

I took another look at the school. That was where I’d met Michelle. Where we’d first started dating. How was I going to tell her? I couldn’t. There was no way. It would destroy her.

Eventually, I replaced Dr. Dre with Tupac, and continued on down the road.

Snubbing a cigarette out in the ashtray, I coughed, felt something loosen in my throat, caught it in my hand, and looked. My palm was slick with blood and saliva. Nothing new— that had been going on for weeks. But now I knew why. Before this, I’d figured it was just a sinus infection. Lots of guys get them from the foundry dust.

I wiped my hand on my pants as I drove by Genova’s Italian Restaurant. They had the best subs in the fucking world; fresh rolls piled high with meat and cheese and veggies. I was definitely going to miss those. I was going to miss a lot of things.

On my way out of town, I passed by the big hill that John and I used to sled down every winter when we were kids. Past the newsstand where I’d gotten my first summer job, delivering weekly newspapers (I’d toss them all in a Dumpster behind the Laundromat and collect my pay from the newsstand owner— lasted three weeks before he caught on). Past the bowling alley, where Michelle and I would go sometimes, when we could find a babysitter for Tommy Junior (I haven’t told you much about T. J. yet— but I will. It just hurts to talk about it, you know?). Past the Fire Hall, where we had our wedding reception. Past the movie theater that still showed The Rocky Horror Picture Show at midnight on Saturdays. Past the strip mall and the fast-food joints.

Past my whole world. My entire existence. The place I’d known for twenty-five years.

It wasn’t much, but I liked it. I hadn’t realized how much I’d liked it until that moment. I mean, I hated this fucking town; the smell of the foundry hung over everything and the dirt from it coated our cars, and the people here just seemed so beaten. They looked tired and worn-out. They didn’t wish for a better life, because they didn’t know that one was possible. All they knew was taxes and late charges and shutoff notices and interest and child support payments. The town was full of churches and temples: Take your pick— Catholic, Episcopalian, Jewish, Methodist, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Baptist, we even had a Mormon temple. But despite all those choices of worship, the town had no faith. No belief. The only thing the people of Hanover believed in was that no matter how bad things were, something worse was lurking around the corner. I’ve got to admit, I thought this way too. I called it my “Theory of Gravity”— no matter how high you flew, gravity was there to pull your ass back down and smash you to bits.

Everything was so run-down— the buildings, the people, the cars— everything. But despite all that, right then, I loved it. I loved it all.

I cruised out of town, took Dogtown Road, and drove through the woods and up to the top of The Hill. We called it The Hill because you could see the entire town from the top of it. I parked, turned off the truck, and just sat there, looking down on everything. I’d always wanted to see more of the world, but I’d never had the chance. Now I never would. This was my world, this town, these woods and fields. They were my world and not for much longer.

Michelle and I had always talked about going on vacation; something within a day’s drive— maybe a trip to Washington, DC, to see the White House and let T. J. gawk at the dinosaur bones in the Smithsonian, or head down to Baltimore to visit the Inner Harbor and take T. J. to the National Aquarium. We’d never had the money to do it though, and even if we had, the foundry paid me at the end of the year for any unused vacation time— and that money came in handy. I found myself wishing now that we’d gone, that we’d visited the museums and the attractions. I imagined lifting T. J. up to see the sharks at the aquarium, or maybe holding Michelle around the waist and staring at the nation’s capitol at nighttime from our hotel balcony, and looking out at all the lights. She liked romantic stuff like that, and to be honest, so did I (though I’d never admit it to John or Sherm— especially not to Sherm).

Another headache kicked in then, this one so bad that it made my teeth hurt. I tried cracking the joints in my neck and rubbing my temples, but it refused to go away. Resolved to suffer, I got out of the truck and stood at the top of the hill, stepping to the edge and silently watching my world below. A breeze rustled through the leaves overhead, and I thought about how it felt on my skin, that cool air. It felt good. It felt so damn good. I didn’t want it to end— just wanted that wind to keep blowing forever. I would miss the breeze when it was gone. I can’t describe it. It was just one of those little things we all take for granted, you know? We never think about the air we’re breathing or how we actually breathe it— our lungs working twenty-four/seven without us ever consciously willing them to.

But the breeze never dies, does it? It just moves on, unlike us. Eventually we stop moving.

I watched the treetops sway in the wind. The leaves were new and green. Just a few months ago, everything had been white and brown and barren. Now the snow was gone, and the whole countryside was alive. A dandelion grew at my feet, and it was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen. Without thinking, I plucked it from the ground and brought it to my nose— killing it. For a second, I felt guilty about that. I couldn’t smell its scent at all so I let it slip from my fingers.

* * *

When I was a kid, one of my mom’s boyfriends was a big Iron Maiden fan. He’d listen to them all the time while working on his car or puttering around the house. Being a hip-hop fan, I was never into heavy metal, but a snatch of lyric came back to me now: “As soon as you’re born, you’re dying.” I hadn’t understood the line at the time, and he’d explained to me that from the very moment we’re born, our cells begin to break down, effectively starting the dying process. It continues all of our lives, until we’re old and gray. It was happening inside me as I stood there on the hill, except that while my good cells were dying, bad cells were growing; growing at an alarming rate, according to the doctor.

I glanced down at the ground. Michelle and I had once made love on that very spot when we were in high school. We’d stopped coming to The Hill after we got married, but sometimes we’d joke about dropping by again, just for old times’ sake. Now we never would.

That was when the full enormity of it sank in, hitting me with the impact of an airplane slamming into the ground. I sank to my knees.

Soon, I wouldn’t feel the wind in my hair and see the green leaves sprouting or the dandelions blooming. I wouldn’t feel the sun or be able to watch the clouds floating by overhead. I would never attend my high school reunion and laugh at those same National Honor Society shitheads who I’d sold pot to, the same ones who were working in fast-food joints or selling used cars now. Michelle and I wouldn’t be going on vacation, or even to the bowling alley, and John and Sherm were going to have to hang out by themselves at Murphy’s Place on Friday nights, and my foreman was going to have to find somebody else to run the Number Two molding machine at the foundry, because I wasn’t going to be doing it for much longer. I wouldn’t be standing there for eight to ten hours a day, wincing every time a hot piece of metal landed on my arm, or picking foundry dirt out of my teeth and ears, or rocking back and forth on the balls of my feet because they hurt from standing so long, and even that I would miss because feeling pain at least meant that I was still alive.

I was never going to catch the new X-Men movie or watch the Orioles make it back to the World Series or see the Steelers go to the Super Bowl and kick some ass. I would never find out what happens next season on 24 or hear the new Wu Tang Clan disc. I’d never take T. J. sledding down the same hill John and I had rocketed down as kids. Never know what Michelle was getting me for my birthday this year, because there would be no more birthdays or anniversaries or Christmases, because no, Virginia, there is no fucking Santa Claus and even if there was, the only thing the fat fuck would leave in my stocking would be a lump of coal, shaped like a tumor and growing at an alarming rate.