Terrible Swift Sword (35 page)

Read Terrible Swift Sword Online

Authors: Joseph Wheelan

Â

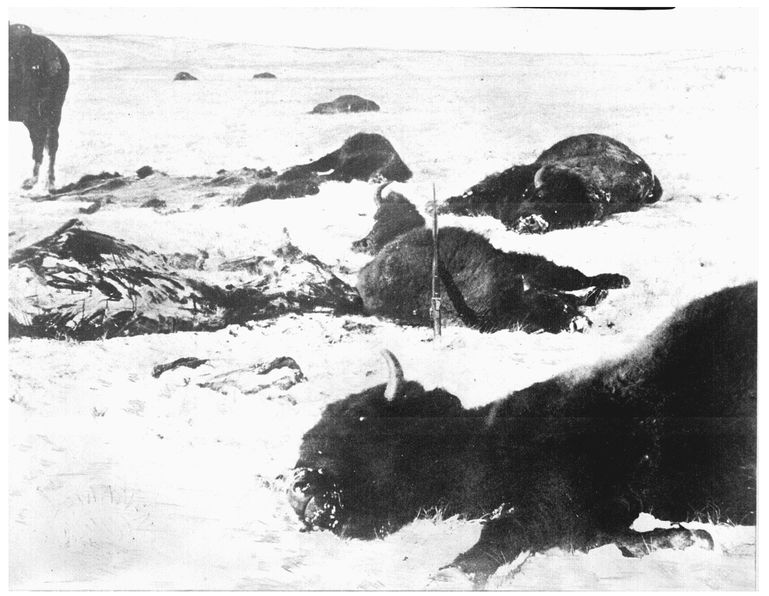

Commercial hunters slaughtered millions of buffalo on the Great Plains. Sheridan, Sherman, and Grant applauded the buffalos' extermination, believing it would force the Plains Indians to accept reservation life.

National Archives

National Archives

Â

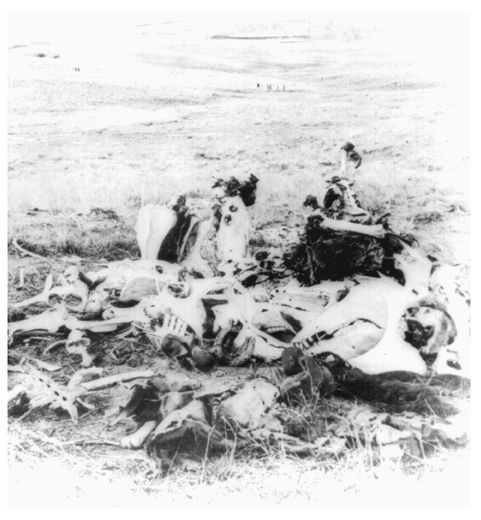

Pile of bones at the place where Lieutenant Colonel George Custer and his command were killed in June 1876 near the Little Bighorn River by Northern Cheyenne and Sioux Indians.

National Archives

National Archives

Â

Chiricahua Apaches on their way to exile in Florida at a railroad siding in Texas. Geronimo is third from left in the bottom row.

National Archives

National Archives

Â

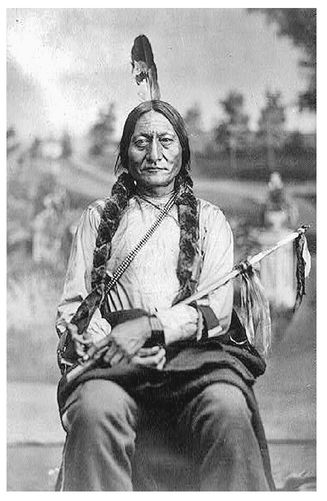

Sitting Bull, chief of the Oglala Sioux, was the last holdout among the Northern Plains Indians.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Â

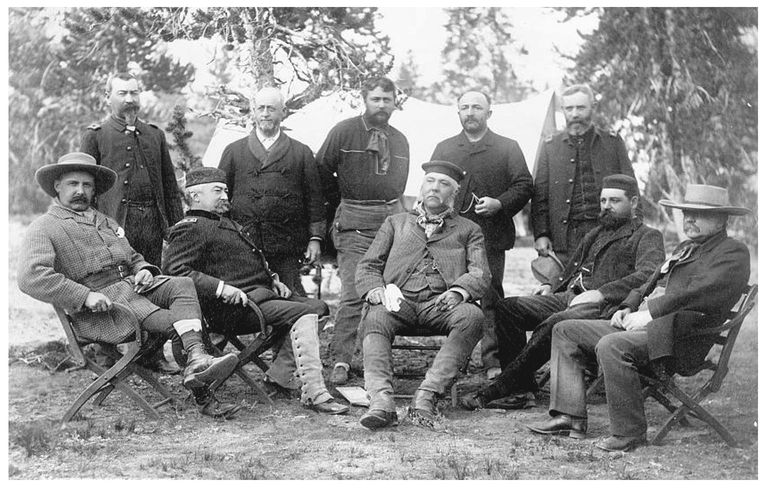

Members of Sheridan's 1883 presidential expedition to Yellowstone National Park. President Chester Arthur is seated at the center, with Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan to his right. Standing at left is Michael Sheridan.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Â

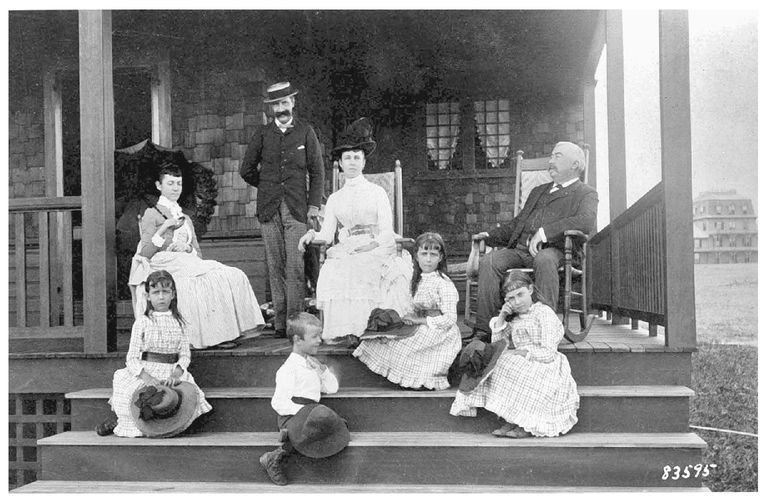

This photograph was taken at the Sheridan family vacation home in Nonquitt, Massachusetts, in 1887, one year before Sheridan's death. Left to right in the rear: Mrs. Michael Sheridan, Michael Sheridan, Irene Rucker Sheridan, and Philip Sheridan. Philip and Irene Sheridan's four children are in the foreground, left to right: Irene, Philip Jr., Louisa, and Mary.

Illinois Historical Society

Illinois Historical Society

Â

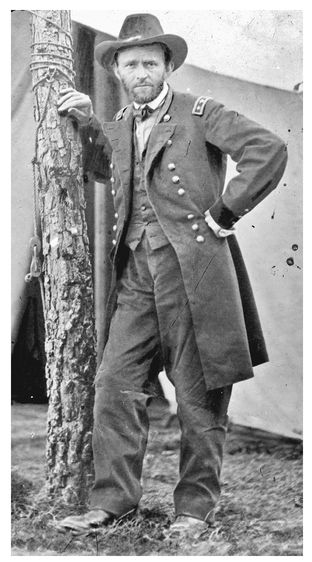

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant

National Archives

National Archives

Â

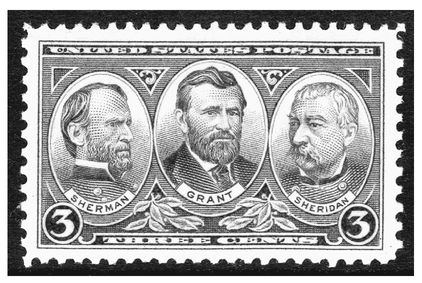

Sheridan, Sherman, and Grant appeared together on a commemorative stamp in 1937, one of a series honoring army and navy heroes.

Â

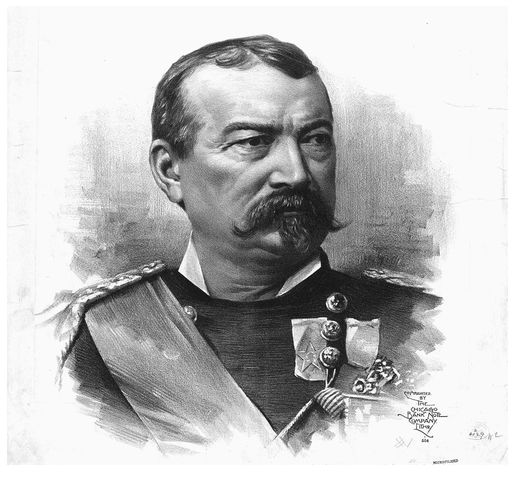

Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan in middle age

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

CHAPTER 11

Waterloo for the Confederacy

MARCHâAPRIL 1865

I have never in my life taken a command into battle, and had the slightest desire to come out alive unless I won.

âPHIL SHERIDAN AFTER FIVE FORKS

1

1

UNION ARMY HEADQUARTERS, CITY POINT, VIRGINIAâIn late March 1865, Philip Sheridan returned to the place outside Petersburg where his journey to national greatness had begun so inauspiciously seven months earlier. Here, in August 1864, General Ulysses Grant had informed him that he would command a new army in the Shenandoah Valley.

Sheridan's mastery of subsequent events had radically altered his status in the Union army. In August 1864, he had been Grant's third choice to command the Army of the Shenandoah. President Abraham Lincoln and the War Department had questioned whether he was up to the job; War Secretary Edwin Stanton had thought him “too young,” and Lincoln had thought him short.

Having seen more fizzle than sizzle in his war leaders, Lincoln had many other reasons to doubt Sheridan. He had pointedly told Grant that the destruction of Jubal Early's army “[would] neither be done nor attempted, unless you watch it

every day and force it.” Among the top military hierarchy, only General William Sherman had been enthusiastic about Sheridan. “He will worry Early to death,” Sherman had predicted.

every day and force it.” Among the top military hierarchy, only General William Sherman had been enthusiastic about Sheridan. “He will worry Early to death,” Sherman had predicted.

Sheridan had wiped the Shenandoah clean of Rebel armies and destroyed its crops and livestock, at once breaking up the Confederacy's conduit to the North and ravaging its breadbasket. His stunning victoriesâCedar Creek, particularlyâhad, with Sherman's conquest of Georgia, helped reelect Lincoln. The people of the North now believed that victory was near and that the Confederacy was doomed.

Consequently, Sheridan was received at City Point on March 26, 1865, with extremely gratifying marks of pleasure and respect by President Lincoln and General Grant, who were there with their wives. Three weeks earlier, Lincoln, his lined face and sunken cheeksâhe had recently lost thirty poundsâmaking him look older than his fifty-six years, had been sworn into office for a second term at the US Capitol in Washington. “Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away,” he had said.

Sheridan found the president “dejected, giving no indication of his usual means of diversion, by which (his quaint stories) I had often heard he could find relief from his cares.” The president, however, displayed his fondness for Sheridan when he reportedly said, “When this peculiar war began I thought a cavalryman should be at least six feet four inches high, but I have changed my mind. Five feet four will do in a pinch.”

Â

WHEN SHERIDAN MET PRIVATELY with Grant to discuss military matters, Grant bestowed a signal mark of the army's soaring faith in Sheridan. His Cavalry Corps would operate as an independent commandâin other words, as the equal of the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the James. He would report directly to Grant and not through George Meade, the Army of the Potomac's commander. With this promotion, Grant, who in person was mild, quiet, and confrontation averse, both neatly rewarded Sheridan's exemplary service and preempted any disruptive clashes between Meade and Sheridan.

Other books

The Billionaire's Bet #4: A Final Game (Erotic Romance with alpha male) by Wild, Clarissa

Indebted: The Premonition Series by Bartol, Amy

Antiques Disposal by Barbara Allan

65 A Heart Is Stolen by Barbara Cartland

The Third Son by Elise Marion

Spawn of Hell by William Schoell

A Catered Romance by Cara Marsi

Four Ways to Pharaoh Khufu by Alexander Marmer

On Paper by Scott, Shae

Raw Desire by Kate Pearce