Texas Summer (15 page)

“One of ’em name C.K. Crow...and the other —”

“Wait a minute. ‘C.K. Crow.’ Any ad-dress?”

“Why ah don’t rightly know they ad-dress. Ah think C.K. work and live out on the old Seth Stevens place, out near Indian River.”

“You know how old he was?”

“C.K.? Why, he was thuty-five, thuty-six year old, ah guess.”

“How ’bout the other one?”

“His name Emmett — everbody call him Big Nail.”

“Emmett what?”

“Emmett Crow.”

“They both named Crow?”

“Yessuh, that’s right.”

“What was they? Brothers?”

“Yessuh, that’s right.”

“Well, how old was he then?”

“Why ah don’t rightly know now which one of them was the oldest of the two. They was always sayin’ they was a

year older

than the other one, each of ’em say that, that he a year older. Then Big Nail, Emmett, he was away, you see, up nawth — in Chicago or New York City, believe it was...but they was both thuty-five, thuty-six year old.”

The policeman closed his book and put it in his pocket.

“They got any folks here?”

Old Wesley nodded. “We’ll look after ’em awright.”

The policeman stood staring at the bodies for a minute.

“What was they fightin’ about?”

“Why now ah don’t rightly know. They got into argy-ment, you see...between themself. Wodn’t nobody could stop it.”

“What were they doin’, shootin’ craps?”

“Well, ah wouldn’t know nothin’ ’bout that! Ah tell you

one

thing, they sho’ weren’t shootin’ no crap in here, ah know that much!”

The policeman stopped at the door, and looked down at Tom.

“Don’t reckon

you

seen anything out of the ordinary goin’ on lately, did you, Blind Tom?”

Blind Tom laughed.

“Nosuh, ah cain’t say ah have.”

“You gonna gimme a

re-

port on it though if you do see something out of the ordinary, ain’t you, Blind Tom?”

“Why sho’ ah is, Mistuh Bud Dawson, you knows that ah is! Fust unusual thing ah see, why ah be down to de station an’ give a re-port, in full!”

They both laughed, and the policeman patted Blind Tom on the shoulder and left.

When the car had pulled away, Harold came out of the room behind the curtain, and people began coming back into the bar.

Blind Tom was singing the blues.

“Ah jest wonder how C.K. feel,” said someone, “if he know he gonna be buried on Big Nail’s money. I bet he wouldn’t like it!”

Old Wesley frowned. “C.K. ’preciate a good send-off as well as the next man. Besides,” he added, “C.K. weren’t never one to hold a grudge for ver’ long.” He looked at Harold, ashen and devastated with shock.

“Ain’t that right, boy?”

XV

I

CAN’T LISTEN

to it again,” said Harold’s mother, walking past the kitchen table, one hand raised to her head. “You’ll have to tell him yourself. I’ll tell your granddad, there’s no use in him hearing it the way you tell it. But you’ll have to tell your daddy.”

“Well, that’s the way it happened, dang it,” said Harold, frowning down at the empty plate in front of him.

“Well, I don’t care, I don’t want to hear it. Now you tell him and then you go wash. We’re goin’ to have supper in a few minutes.”

She walked out of the room and left Harold sitting alone at the table. Outside the dogs were barking, and he heard his father on the porch, stamping his feet, kicking the mud from his shoes; then the door opened and he came inside, still stamping his feet as though it were winter. He leaned the shotgun against the wall under a rack of others.

“I want you to clean that gun after supper, Son,” he said. “Where’s your mother?”

“She’s upstairs.”

“Looka here, boy,” said his father, smiling now, holding up a brace of fat bobwhite quail, “ain’t them good ’uns?”

“C.K.’s dead, Dad,” said Harold, just as he had planned, as gravely as he could, not feeling anything except trying to measure up to the adult type of seriousness he believed the words must have.

“What’re you talkin’ about, Son?” demanded his father, scowling in anger and impatience. “Didn’t you and him pick up that feed?” He stamped over to the sink and laid the birds down there to turn and face the boy and have it out. “Now what’re you talkin’ about?”

And for Harold it was only then, with the moment of his father’s disbelief, that the reality of it cut through his shock and fell across his heart like a knife. Something jumped and caught inside his throat and knotted behind his eyes. He looked down at the table, shaking his head, and then the thing inside his throat, burning behind his eyes, broke loose, in a short terrible burst, and he stiffly raised one arm to his face to try and choke away the terrible sobs, and the incredible tears — not the kind of tears he had known before, but tears of the first bewildering sorrow.

His father said nothing, frowning in consternation; then he came over and stood by him, and finally put one hand gently, awkwardly, on his shoulder.

At the supper table, no more was said about it, until once when Harold’s father sat for a moment gazing dis-traitly at the knife in his hand. “Damn niggers,” he said softly, “what did they git into a fight about anyway?”

“Drink some milk, Son,” said his mother, raising the big pitcher, “you’ve got to have something.”

“What was it they was fightin’ about?” repeated his father.

Harold dumbly watched the glass in his hand, the white milk tumbling in. He pushed the glass away.

“Aw, I dunno,” he said stiffly, “they got into argument — about one thing and another, and then they got to fightin’ — wasn’t nobody could stop it.”

“Hadn’t been a-shootin’ crap?” said his old grandfather, brooding forward over his plate toward the boy like a hawk.

“No sir,” said Harold, “they weren’t doin’ nothin’ like that.”

The old man grunted and kept on eating.

XVI

I

N THE OPEN-END

dirt-floor shed, Harold sat in the same place where C.K. used to read his

Western Story.

With the .22 rifle raised to his shoulder, he fired shot after shot into a paper target about fifteen feet away. He fired until the bull’s-eye was completely shot away, and in its place only a ragged hole. But he continued shooting until the gun was empty.

He was sitting cross-legged, the shell-box and fruit-jar of grass at his feet. Using the knife that had skinned the rabbit and scooping with his hands, he dug a hole in the soft earth and put the two containers in it and covered them over. He gazed down for a long moment at the place where they were hidden. He knew they were buried deep enough not to be discovered, but not so deep that he couldn’t get to them, if he should ever want to.

A Biography of Terry Southern

Terry Southern (1924–1995) was an American satirist, author, journalist, screenwriter, and educator and is considered one of the great literary minds of the second half of the twentieth century. His bestselling novels—

Candy

(1958), a spoof on pornography based on Voltaire’s

Candide

, and

The Magic Christian

(1959), a satire of the grossly rich also made into a movie starring Peter Sellers and Ringo Starr—established Southern as a literary and pop culture icon. Literary achievement evolved into a successful film career, with the Academy Award–nominated screenplays for

Dr. Strangelove, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

(1964), which he wrote with Stanley Kubrick and Peter George, and

Easy Rider

(1969), which he wrote with Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper.

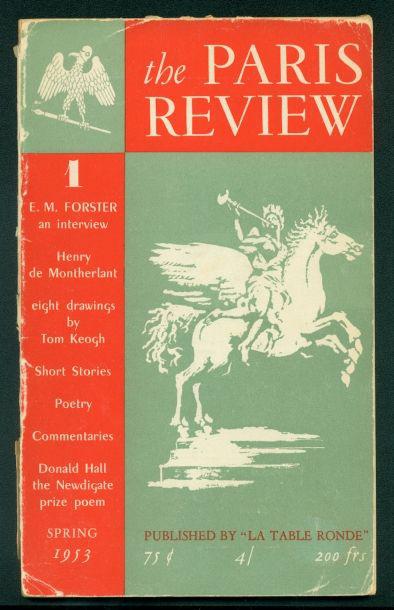

Born in Alvarado, Texas, Southern was educated at Southern Methodist University, the University of Chicago, and Northwestern, where he earned his bachelor’s degree. He served in the Army during World War II, and was part of the expatriate American café society of 1950s Paris, where he attended the Sorbonne on the GI Bill. In Paris, he befriended writers James Baldwin, James Jones, Mordecai Richler, and Christopher Logue, among others, and met the prominent French intellectuals Jean Cocteau, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Albert Camus. His short story “The Accident” was published in the inaugural issue of the

Paris Review

in 1953, and he became closely identified with the magazine’s founders, Harold L. Humes, Peter Matthiessen and George Plimpton, who became his lifelong friends. It was in Paris that Southern wrote his first novel,

Flash and Filigree

(1958), a satire of 1950s Los Angeles.

When he returned to the States, Southern moved to Greenwich Village, where he took an apartment with Aram Avakian (whom he’d met in Paris) and quickly became a major part of the artistic, literary, and music scene populated by Larry Rivers, David Amram, Bruce Conner, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and Jack Kerouac, among others. After marrying Carol Kauffman in 1956, he settled in Geneva until 1959. There he wrote

Candy

with friend and poet Mason Hoffenberg, and

The Magic Christian

. Carol and Terry’s son, Nile, was born in 1960 after the couple moved to Connecticut, near the novelist William Styron, another lifelong friend.

Three years later, Southern was invited by Stanley Kubrick to work on his new film starring Peter Sellers, which became,

Dr. Strangelove

.

Candy

, initially banned in France and England, pushed all of America’s post-war puritanical buttons and became a bestseller. Southern’s short pieces have appeared in the

Paris Review

,

Esquire

, the

Realist

,

Harper’s Bazaar

,

Glamour

,

Argosy

,

Playboy

, and the

Nation

, among others. His journalism for

Esquire

, particularly his 1962 piece “Twirling at Ole Miss,” was credited by Tom Wolfe for beginning the New Journalism style. In 1964 Southern was one of the most famous writers in the United States, with a successful career in journalism, his novel

Candy

at number one on the

New York Times

bestseller list, and

Dr. Strangelove

a hit at the box office.

After his success with

Strangelove

, Southern worked on a series of films, including the hugely successful

Easy Rider

. Other film credits include

The Loved One

,

The Cincinnati Kid

,

Barbarella

, and

The End of the Road

. He achieved pop-culture immortality when he was featured on the famous album cover of the Beatles’

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

. However, despite working with some of the biggest names in film, music, and television, and a period in which he was making quite a lot of money (1964–1969), by 1970, Southern was plagued by financial troubles.

He published two more books:

Red-Dirt Marijuana and Other Tastes

(1967), a collection of stories and other short pieces, and

Blue Movie

(1970), a bawdy satire of Hollywood. In the 1980s, Southern wrote for

Saturday Night Live,

and his final novel,

Texas Summer

, was published in 1992. In his final years, Southern lectured on screenwriting at New York University and Columbia University. He collapsed on his way to class at Columbia on October 25, 1995, and died four days later.

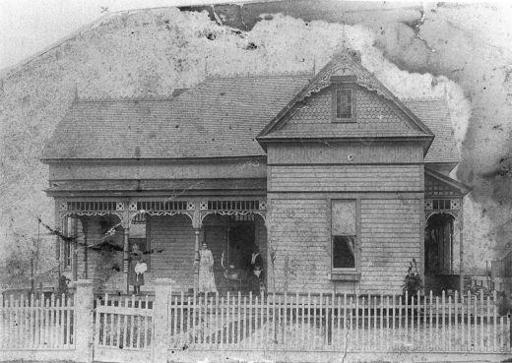

The Southern home in Alvarado, Texas, seen here in the 1880s.

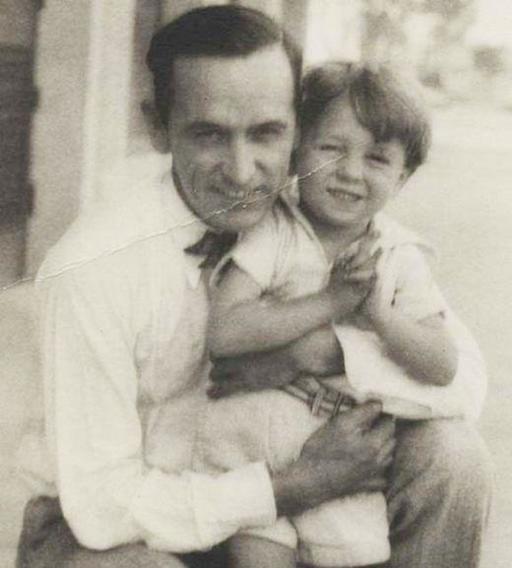

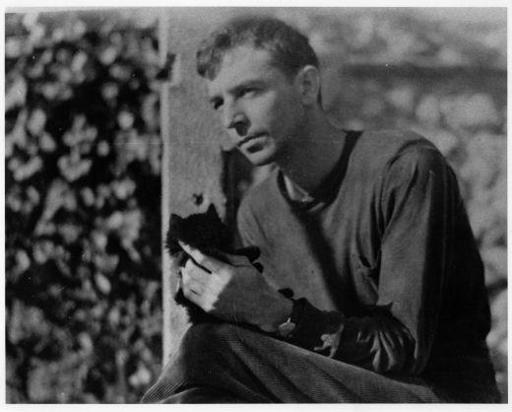

A young Southern with a dog in Alvarado, his hometown, around 1929.

Terry Southern Sr. with his son in Dallas, around 1930.

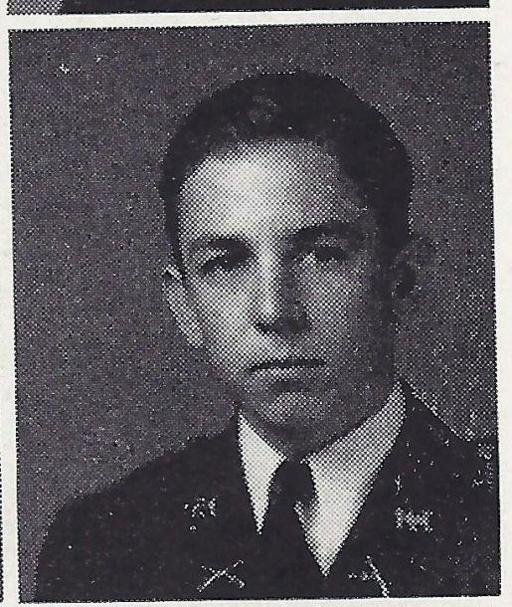

Southern’s yearbook photo from his senior year at Sunset High in 1941.

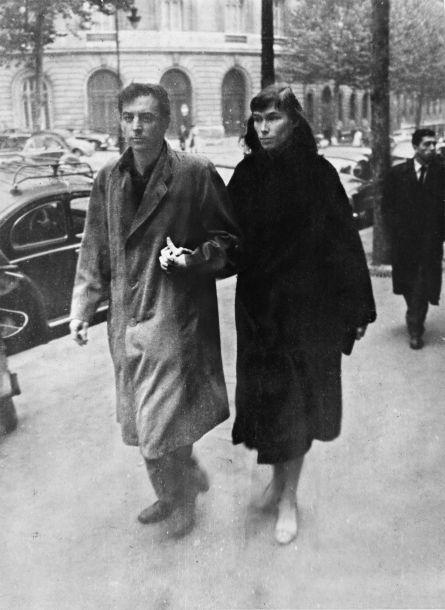

Southern before World War II. He was able to use the GI Bill to spend four years studying in Paris.

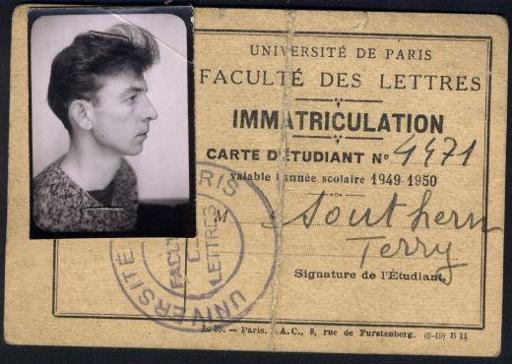

Southern’s 1949 student ID card from the Sorbonne. While abroad, he met many of the people with whom he would collaborate, including Henry Green, Richard Seaver, Alex Trocchi, William Burroughs, Ted Kotcheff, George Plimpton, and Mason Hoffenberg, with whom he wrote

Candy

(1958).

The first ever issue of the

Paris Review

(Spring 1953), which included Southern’s short story “The Accident.”

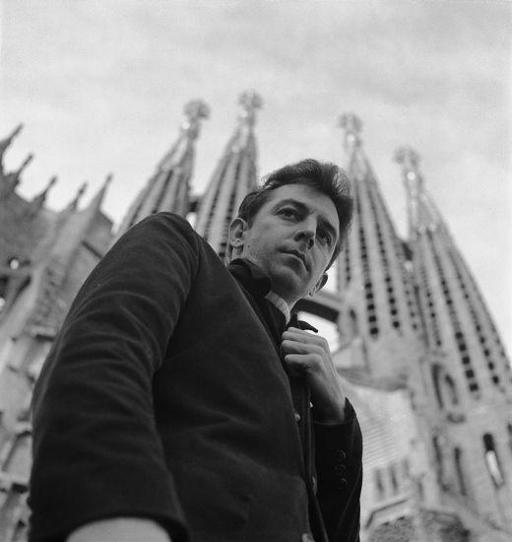

Outside Gaudí’s Sagrada Família Church in Barcelona in 1954. (Photo by Pud Gadiot.)