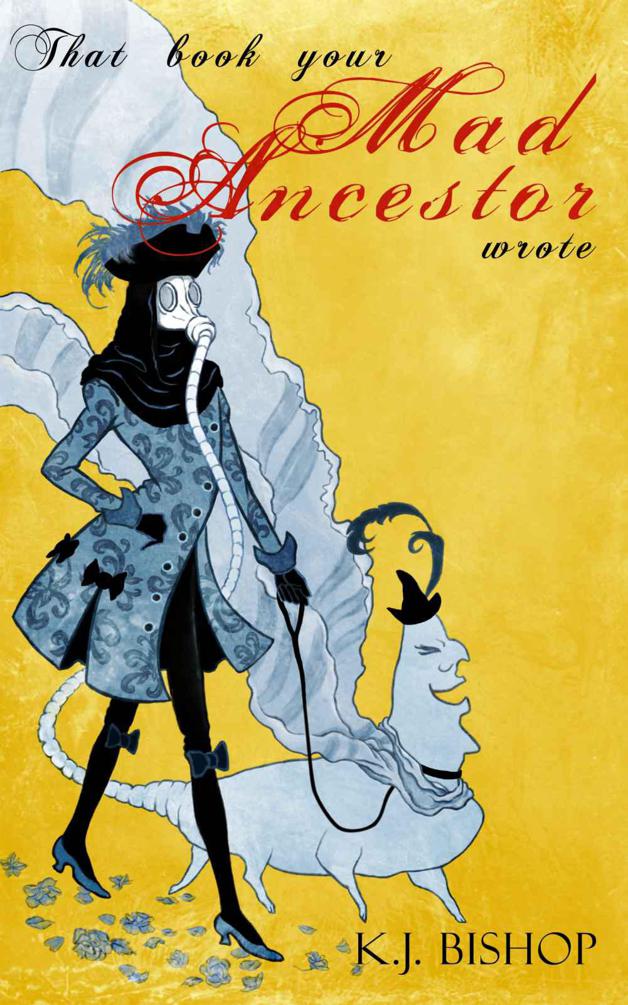

That Book Your Mad Ancestor Wrote

Read That Book Your Mad Ancestor Wrote Online

Authors: K.J. Bishop

THAT BOOK YOUR MAD ANCESTOR WROTE

K.J. BISHOP

CONTENTS

THE CRONE MEETS HER SON (ON A BATTLEFIELD)

Mona Skye, the duellist and poet of lately tragic fame, lay with her angular limbs folded atop brocade cushions in a corner of the smoking-room beneath the Amber Tree café. Fever made her long face beautiful; it reddened her lips and caused her grey eyes to sparkle and smoulder. The lean woman had gained a perversely tender grace as she wasted towards frailty. Even her pale hair seemed softer and brighter.

The disease turns her into that old cliché, the beautiful and beloved thing that can

live only a short while

… Vali Jardine swallowed down the sour taste of anger with a mouthful of drowsy smoke from the narghile, a brass extravaganza squatting like an artificial octopus on the floor between them.

Anger had been a close companion to Vali since the night of the

summer Lantern Casting, when Mona had drunkenly sworn to let Death catch her, since he seemed to want her so much. She would face the grinning bastard, seduce him and make him take her. She had made this announcement to discomfited onlookers in the crowd gathered on the Volta’s bohemian west bank to watch the thousands of paper lights floating past the view of sleepless workshops and foundries across the river. The next morning she had rejected her medicines, throwing all her tonics and powders out onto the little courtyard below the apartment she and Vali shared.

‘

She’s asleep,’ a man’s voice came softly out of the gloom on Mona’s other side. A black damask sleeve reached across the cushions and long fingers lifted the pipe from her hand to drape it around the narghile’s stem. Another pipe was raised to lips half-hidden in the shadow of curtainous black hair. The man, whose name was Gwynn, was a sometime adventurer from the snow-swept north of the world. He and Mona had once been comrades-in-arms and sweethearts down in the canyon country east of the Teleute Shelf. The love-affair had been uncomplicated and brief and their friendship had endured. Separate routes had brought them to Sheol, on the brink of the great plateau. Travellers no longer, now they both played the southern city’s games of easy money and fast death.

Gwynn

drew on the pipe, and through a nebula of smoke regarded his old inamorata and the woman who was her lover now.

‘

Vali, will you hear the advice of a friend?’

‘

I’ll listen…’

‘

Get her out of Sheol. Take her somewhere cleaner.’

‘

Why? Clean air might be good for her lungs, but it won’t cure a death-wish. We might as well stay here where at least there’s some civilisation.’ Vali could hear how bitter she sounded.

‘

I’m not talking about the air,’ Gwynn said. His greenish eyes were slitted. ‘This city is venomous. Some people it paralyses, others it injects with despair. It doesn’t like us. You should leave and take her with you.’

‘

And go where?’

He exhaled a dense stream of smoke.

‘Anywhere else.’

‘

Ha! I don’t see you packing your bags and moving out, Mr Sage Advice.’

Gwynn laughed dryly.

‘I tried once, but I got homesick.’ He made the pipe bubble once more, then pulled his gloves on and buttoned them, and raised himself off the cushions. ‘I’m tired,’ he said, ‘and so are you. I’m going to get us a cab.’

Vali watched the back of his damask tailcoat retreat into the slumbering recesses of the room

, in which the lamp-lit smoke hung as though over a battlefield where sleep was the worst that could happen. Almost all of Mona’s friends had deserted her, fearing they would catch her illness, or else motivated by embarrassment. She wondered whether it was love, loyalty, or some other reason that kept Gwynn hovering near the flame.

And what about you? Why are you crisping your wings when she rejects you along with the rest of the world?

She addressed her reflection in the narghile’s polished vase, as if the image in the maternal figure of the water-pipe had some power to explain her own soul to her. But the distorted little picture in the bulging metal showed her no oracle, only a woman of a certain tough genus, in a much-travelled coat of bottle-green suede, hair rolled in the long, tight dreadlocks worn by the military clans of Oran, her homeland in the Shelf’s western tropics. She had kept the style for aesthetic reasons, though technically she no longer had the right to wear it. It went with the old scars faintly marking her dark face.

Her own notions of justice had caused her to hang up her mask and withdraw from the

milieu of the juridical theatres. She preferred to sell her skills on the street, where there was no affectation of fairness and right. It was an ethic of sorts, foreign to Sheol’s codes of living; but then, it was a common saying that everyone in Sheol was a foreigner.

And we blow here like leaves in a gale, and sometimes we find love

. Mona had said that last autumn, a year ago now, in a briefly voguish bar on Arcade Bridge.

Love turns us all a little mad

,

Vali’s misshapen reflection seemed to say.

She

felt torpid, but her mind was unquiet. The little indulgence in opium had not brought her serenity, much less euphoria, and she mocked herself for succumbing to the stuff’s promises. Then again, perhaps she should have indulged more. She found her boots and tugged them on, her fingers seeming to float as they dealt with the array of buckles and laces.

If someone happens to want a piece of you now, Jardine,

she thought,

the management’ll be cleaning you off the carpet for a week.

Over the troubled sound of Mona

’s breathing, Vali became aware of a scratching noise behind her, as of a mouse scuttling over slate. She looked around and saw a reedy, fair-haired teenager perched on the edge of a divan, writing hastily in a thick notebook. Vali would have taken him for one more desperate poet seeking inspiration in smoke dreams, if she had not caught him glancing furtively across at her with alert eyes. The damned press! Well, she would see what lies this one was writing.

She rose, advanced, and, glaring, snatched the notebook out of his hand. She skimmed the pages:

Society Report: Mona Skye, the renowned sabreur, sonneteer and despiser of the world, observed unconscious in a drug den on the notorious Sycamore Street strip: it seems the end is near for the self

-destructing heroine…

At the Cutting Edge: Mona Skye’s worsening condition has cast a gloom over the demimonde and beyond. Conversations are not sparkling. The beautiful people preoccupy themselves with sedatives. Gallants and quaintrelles dress like undertakers. Expect the chic look this winter to be formal, functional and funereal…

Art Update: Is Mona Skye’s slow suicide art? Many think so. While predictably negative noise issues from conservative quarters, public opinion seems to be with the progressive critics who are claiming that death as performance is the ultimate art-form, an art against which there can be no appeal. Watching Mona Skye, one is exposed to an exquisite release of energies as her body, as though whispering secrets to a confidant, reveals new stages of its degenerative journey. Killer and victim are one, coexisting in a symbiosis of extended intimacy…

It was only the usual drivel, merely aimed at a higher class of audience, but Vali felt the pressure of fury rising inside her like steam in a boiler. Her mind flung up an image of an autopsy conducted while pretentious types loafed around the slab drinking trendy wines and picking at hors d’oeuvres.

S

he willed herself to composure. Icily she said to the boy, ‘It is in bad taste to serve up a person’s suffering as entertainment for the chattering classes.’

He was wearing a suit that needed some cleaning and a leather coat that was at least two sizes too bi

g. His fingers twitched nervously.

‘

Ma’am,’ he said, ‘the last thing I want to do is offend. This city looks to your former profession for inspiration in everything, including matters of taste.’

Unfortunately, it was the truth. Vali wondered how, even in her present state, she had forgotten. Every day she saw children playing

‘Chop-Chop’ and ‘Kill ’Em All’ on the pavements. Duellists were fêted in popular culture. Their images were made into character dolls and reproduced on household items and souvenirs. Wildly fictionalised, lurid stories about their adventures and private lives were supplied to an eager public in cheap magazines with titles like

Corinthian,

Hearts and Blades

and

Tales from the Theatre of Woe.

Sometimes she saw dolls with her own face in secondhand shops, going cheap. Merchandise featuring Mona’s image, on the other hand, was currently riding a wave of popularity. Now, it seemed, Mona’s lengthy embracing of death had attracted the attention of the bourgeoisie.

It is she who is guilty of bad taste; she

’s making a shabby exhibition of herself, and I’m as guilty for accepting a part in it,

Vali thought with a dreary sense of entrapment. She was grateful to the opium for numbing some of her embarrassment.

‘

I have a duty to the people,’ the kid was explaining. ‘They must have information.’ He drew himself up and tilted his head to look Vali in the eye. ‘The freedom of the press is sacred, ma’am.’