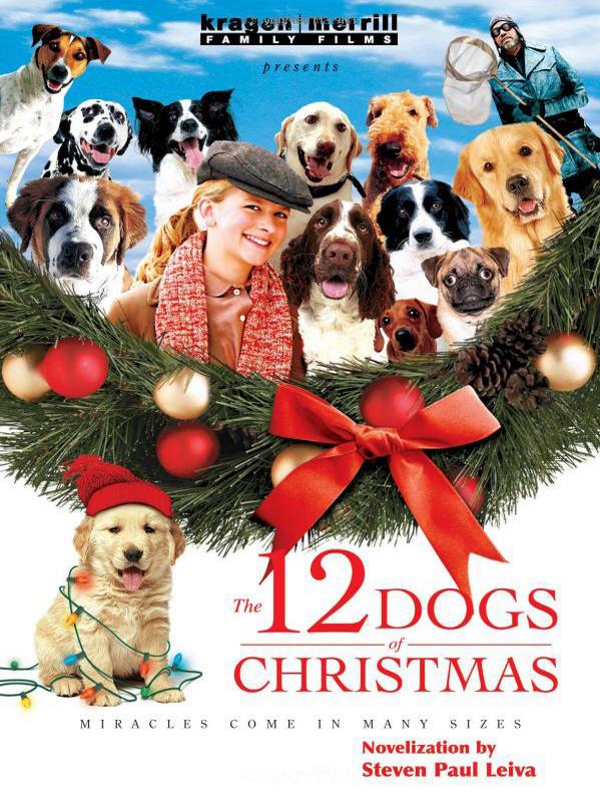

The 12 Dogs of Christmas

The

12

DOGS

of

CHRISTMAS

By Steven Paul Leiva

Photographs by Ken Kragen

Based on the screenplay by Kieth Merrill

Story by Kieth Merrill and Steven Paul Leiva

Based on the book

The Twelve Dogs of Christmas

by Emma Kragen

And a screen treatment by Steven Paul Leiva

© 2007 by Kragen and Company

Photographs by Ken Kragen; photograph of Emma on the train by Don Muirhead

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meansâelectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherâexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Thomas Nelson. Thomas Nelson is a trademark of Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Thomas Nelson, Inc., titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fundraising, or sales promotional use. For information, please email [email protected].

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Leiva, Steven Paul.

12 dogs of Christmas / by Steven Paul Leiva based on the screenplay by Kieth Merrill ; story by Kieth Merrill and Steven Paul Leiva based on the book The twelve dogs of Christmas by Emma Kragen.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4003-1053-1 (tradepaper)

ISBN-10: 1-4003-1053-9

I. Merrill, Kieth, 1940â II. Kragen, Emma. Twelve dogs of Christmas. III. 12 dogs of Christmas (Motion picture) IV. Title. V. Title: Twelve dogs of Christmas.

PZ7.L53724Aad 2007

[Fic]--dc22

2007013515

Printed in the United States of America

07 08 09 10 11 HCI 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my daughter Miranda

Dog lover

nonpareil

Contents

16. A Small Change of One Heart

The author wishes to give his thanks and admiration to Ken Kragen, gentleman and scholar of the sky. Appreciation must be given to Kieth Merrill and the full cast and crew of the film,

The 12 Dogs of Christmas

, for without them there would never have been this novel. I'm sure Ken and Kieth join the author in thanking Emma Kragen for her doggone wonderful and lyrical changes to an old classic, thereby making a new classic. And everyone involved in this project must give thanks to Amanda Martin for always holding things together with wit and charm, only two of the many attributes the author married her for.

Max was a Poodle. Not one of those little Poodles, a

Miniature or a Toy with puffy and fluffy fur finely cut and

clipped like bushes in a French garden, who spent their days

sitting in the laps of ladies who also seemed finely cut and

clipped. No, Max was not one of those Poodles; Max was a

Standard Poodle, proudly standing two feet tall, and

although he was well groomed, it was not in a puffy and

fluffy way but in a handsome boy-dog way with a coat of

beautiful black curls.

Max had led a privileged life. He was the pet of Thaddeus

Whiteside, the kindest man on the Upper East Side of New

York City. Max's life had been one of warmth and food and

love and play. Especially play, for Mr. Whiteside, despite his

hair being as white as white could be, was more like a human

boy who liked to laugh a lot than he was like the other men

who used to come to Mr. Whiteside's beautiful four-story

house on the Upper East Side to talk to him about what they

called “business.” Now Max did not know what business

was, but it certainly was not play, because none of the men

ever laughed about it.

“It's the Depression, Mr. Whiteside,” one of the men had

said one day. “You can no longer afford this house.”

And then their beautiful house was not as warm, and the

food was not as plentifulâbut the love was just as strong,

and Mr. Whiteside still laughed when they played . . . until

the day when some other men came and started taking

things away, including Max's big, beautiful doghouse that

had always sat in a corner of Mr. Whiteside's bedroom and

was Max's very special place.

Did all this make Max sad? Of course it did. And when

a dog is sad, he can whimper to let his human know, but if

a human is as kind as Mr. Whiteside, he doesn't have to

hear his dog whimper, for he can see it in his dog's eyes.

Max's eyes never got so sad as when the other humans

were moving things out, and Mr. Whiteside had to put Max

in a wooden, cage-like box.

“I'm sorry, Max,” Mr. Whiteside said. “I'm very, very

sorry, but I can't take care of you any more. But you'll be

okay, I promise. Look . . .” Mr. Whiteside picked up a copy

of LIKE magazine, his favorite magazine because it always

had big photographs he could show Max. “See this lady?”

Mr. Whiteside asked, pointing to a picture of a woman in

front of a barn surrounded by a small group of dogs. “This

is Cathy Stevens. They're calling her the Dog Lady of

Doverville. Doverville is a town in Maine that has outlawed

dogs! Can you imagine such a thing, Max, outlawing dogs?

But since this Cathy Stevens actually lives just outside the

town limits, she's set up a dog orphanage to take in all the

dogs the townspeople have to give up. Well, I figured if she

can take in Doverville's dogs, she can take in one more dog

from New York City. So that's why I've put you in this traveling

case and . . .”

Mr. Whiteside stopped talking when he heard a big crash

coming from outside. He rushed to the window, opened it,

and looked down one story to the street below where all his

beautiful things were being loaded onto a truck.

“Please be careful with that dresser! It belonged to my

mother!” Mr. Whiteside yelled down below.

And from below came a not-so-friendly voice that said,

“What do you care? It's not yours anymore!”

And now, as Mr. Whiteside turned away from the window,

Max saw the sadness in his eyes. It was a sadness he had

never seen in Mr. Whiteside before . . . and a sadness he

would never see in Mr. Whiteside again. At that moment, one

of the other big men came and took Max away. They locked

the box that looked like a cage with a shipping label that read:

PLEASE DELIVER MAX TO THE DOG LADY, C/O DOG

ORPHANAGE, DOVERVILLE, MAINE.

Emma O'Connor was a tomboy. Whether she was a natural tomboy or a tomboy because of her circumstances, even she was not sure. She might very well have liked to have worn pretty and frilly dresses, and she might very well have liked to have gone to fancy tea parties, but she lived in Pittsburg in 1931 when the country was suffering through the Great Depression, a time when very few had the money to be frilly or fancy. And it was just she and her father. Her mother had died several years before, and her father knew nothing about the raising of girls. So he dressed her in knickersâ those funny boy pants that never made it down to the anklesâwhen she went to school, and he dressed her in an old pair of his overallsâslightly adjusted for her sizeâwhen she went to work.

Even though she was only twelve years old, it was necessary for her to work to help earn enough money for them to live. Her father worked every job he could find, but there just weren't that many jobs for men those days. So Emma delivered the

Pittsburg

Herald

to all who could afford the luxury of a newspaper. Once a week she also collected all the bacon grease that her neighbors had saved for her in empty coffee cans. She could sell the grease for a few dollars to a company that used it to help make soap.

Emma O'Connor was a tough kid. Not mean, mind you, she was anything but mean, but toughâbecause she had to be.

It was the beginning of the Christmas season, and no twelve-year-old girl could be tough when visions of brightly wrapped presents appeared out of nowhere, and desires for a warm hearth and hot cocoa kept tugging at her, but had nowhere to take her.

Is it any wonder that Emma was a bit sad when she was finishing up her paper route that day? It was almost Christmas, and yet the headlines on her papers had nothing cheerful to report. And when she told Mr. Lawson that she was collecting for the paper that day, he said to her, with some embarrassment, “Can't afford it anymore, Em. Take us off your list.” Then, as she did everyday, she walked past the local Hooverville, the empty lot where people who were homeless because of the Depression had built a bunch of makeshift shelters out of box-wood, cardboard, and scraps of metal. Well, that was sad every day, but even sadder around Christmas. Even the Salvation Army carolers, singing the songs Emma had always loved, seemed a little sad. Emma stopped to listen for a minute, gave them a smile, and wished she could have put a nickel into the collection pot, because poor as she was, she knew a lot more people had more reasons to be sad than she did. For at least she had her father, and he had her, and they had always taken care of each other, so everythingâ eventuallyâwould be all right.

Wouldn't it?

When Emma got home to their dim, cold apartment, she found her father staring at an official-looking document. “Dad?” she said as she put down her paper route earnings on the desk. Her father, whose name was Douglas, looked at her and said straight out, because he knew his girl was tough, “Em, we've been evicted. We have to leave tomorrow.”

“What?”

“We have to move out.”

“Where are we going to live?” Emma asked, fearful of the answer. “Not the Hooverville, we aren't going toâ”

“No!

We

are not. I'm going to send you to your Aunt Dolores.”

“I have an Aunt Dolores?”

“I've never told you about her, have I? Well, yes, you do, sort of, it's a long . . . Look, she's a good woman, and I'm sure she'll take you in. She lives up in Maine, in a little town that I remember being quite beautiful called Doverville.”

“But I want to stay with you!”

“Of course you do, honey. And I want you to, and you will again soon, I promise. But not right now. Right now I've got to figure out how to make things right, Em. I've got one last chance to be a very good fatherâand a very good man. I have decided that the country may be in a depression, but that doesn't mean

I

have to be. I'm not going to be. I'm going to go out there, no matter what the odds, and find a way to take care of you. But I've got to do it alone, Em. I can't ask you to go through what I may have to go through until I find that way.”

Emma was confused. What her father was saying both comforted herâand scared her.

Emma did not sleep much that night. She passed the long hours weeping for her father and humming one of her mother's old songs. She alternated between the two, calming her sobs with the memory of her mother's song. She couldn't stand for her father to hear her cry through the paper-thin walls of her room. He had enough to worry about right now.