The 22 Letters (5 page)

Authors: Richard; Clive; Kennedy King

“Yes, sir,” said the sergeant stolidly. “Just what I said, sir. If it's mountains the general will want to know. If it's a bit of a cloud that

looks

like a mountain he won't. He'll be able to tell the difference right enough, when he sees it with his own eyes.”

Zayin was about to explode with anger, but he kept silent. He remembered what he had so often said to his men about believing his own eyes. He strode without speaking to the top of the next rise and halted, scanning the horizon and shading his eyes with his hand. Just above the skyline to the North was a line that might have been a low dark cloud, but he knew that it was not. It was the jagged peak of a range of mountains. And he had the feeling that they must hold the secret of something he wanted to know, and he resolved that he alone would be the one to discover this secret.

It was in the afternoon a day or two later that they came to the foothills of the mountains. Zayin gave the order to pitch camp a little earlier than usual: the end of the empty plain was as good a place as any to halt, and exploration of the mountains would have to wait until the next day. But in spite of the day's long march he felt restless as the soldiers went about their work, erecting the tents and preparing the evening meal. There were still some hours of daylight left, and the feeling that he himself must discover the secret of the mountains was too strong for him. So, calling his under-officers together, he told them to see to the posting of sentinels for the night, and announced he was going alone up the nearest hill. The sergeant who was his right-hand man offered to go with him, but Zayin insisted that no escort was necessary, and set off up the slopes.

It was a pleasant change to be back in the mountains.

Of course, the view from the first low crest revealed only a higher crest beyond. But there would be no harm in going on alone a little farther to see what lay on the other side. He went down to a shallow ravine and scrambled up the other side among great boulders.

To his surprise, when he reached the crest he found that the ground fell away before him even more steeply and swept down to the floor of a broad valley. The setting sun flooded it with light, and shone, too, on innumerable objects in the bottom of the valley, white, brown, and black, that cast long shadows on the green pasture. What were they? Boulders? No, some of them were moving. Men? No, their movements were like those of animals grazing. It was difficult to tell size or shape from that distance. Heedless of the lengthening shadows and of the distance from the camp, Zayin let himself go over the edge of the valley, slipping, sliding, catching at shrubs as he could, sending showers of stones trickling hundreds of feet below him to the bottom. He arrived at the foot of the slope in an avalanche of rocks and soil, uncertain whether he was on his head or his heels, and as he crashed into the bushes that grew there a great creature leaped out of the shadows and bounded snorting across the turf. When it came to the groups in the distance they, too, plunged and tossed and fled away to the other end of the valley.

Zayin picked himself up, shaken and dizzy, and strained his eyes after the retreating creatures. What had the old man of the plains said? That it was “like the running of gazelles and the dancing of young women.” The movement of these beings was indeed a beautiful sight in the evening sun, though all he had seen was their rounded hindquarters and flowing tails. But what of the rest of their bodies. Had he seen a human face and arms? What a fool he had been to disturb them in such a clumsy manner. Whatever they were, they were nervous, timid creatures, easily scared. He must follow them, quietly, and show them that he came in peace.

The valley was much longer than he had thought, and it would soon be quite dark. But Zayin kept on. Soon the foot of the valley walls were in shadow, then the shadow line crept up them and the dusk gathered. The stars came out, and at length Zayin was walking over the smooth turf in darkness. And it seemed that as he walked, the creatures he was looking for returned softly to surround him. He could hear snorts and stamping hooves, and could make out dim shapes, a little darker than the darkness. One, apparently bolder than the rest, was approaching him, step by step. Zayin stood quite still. “Come,” he said quietly. “Come, we are friends.” The creature came nearer in the darkness. Zayin held out his hand until he could feel its breath. His other hand was on his sword, but somehow he felt that the creatures were friendly, whatever they were. But they kept their distance, and they would not speak.

Zayin kept walking. He must find somewhere to spend the night. Through the gloom he thought he could make out a shape that was too square and too big to be an animal. He approached it warily: close to it seemed to be some kind of shelter with one open side. Was there something stirring in it?

“Ho there!” called Zayin, firmly. There was a sudden movement in the darkness.

“You in there!” he called. “Come out so I can see you!” Part of the darkness seemed to bunch itself together and launch itself upon Zayin. He side stepped and lunged with his sword. Whatever it was swerved past him, and as it did so dealt him a powerful blow on his sword arm, making him drop his sword and curse. Then it thundered away into the night, with a sound as of more than two feet. Zayin felt around for his dropped sword, rubbed his aching arm, and decided that these creatures had little sense of hospitality. He went into the shelter, satisfied himself there was nothing there but a pile of soft vegetation, laid his sword on the ground and lay down himself. He was very tired and there was nothing to do but go to sleep like this.

No time seemed to have passed before he sat up in the morning sunlight and looked around him. Horses! they were grazing on the dewy grass, or just standing looking at him inquisitively.

They were, after all, animals with four legs and curved necks that ate grass like cattle. And yet Zayin could not feel disappointed. He had heard of horses, certainly, and had seen them, harnessed to chariots, when he had watched Pharaoh's army from the mountains. But he had never been so close to them before, or seen them running free. He was charmed as he watched the colts gamboling in the sun or nudging up to their dams. How much more pleasant their company was than the grumbling soldiers.

But Zayin suddenly felt a twinge, or rather two. A twinge of conscience and a twinge of hunger. He had deserted his army, and he could not stay here and eat grass. He would have to make his way back to the camp.

It took him longer than he had expected to walk back over the floor of the valley, and he could see that climbing the sides would be very much more difficult than sliding down had been. He started the laborious ascent, trying to avoid stretches of loose rock. And then, as he climbed, he noticed a figure descending toward him from above. By the armor he seemed to be one of his soldiers. Zayin stood on a rock and waved, and the figure waved back and continued to come down toward him, almost as recklessly as he had himself done the day before. Soon Zayin was able to recognize the man as the sergeant. He glissaded toward Zayin in a scramble of stones and tried to stand to attention and salute.

“The gods be praised,” the sergeant panted. “You at least are safe, sir!” The man seemed to be at the extreme of exhaustion.

“What's the matter, man? What's happened?” Zayin demanded, suddenly very concerned.

“Ah, sir, it was only too true about the monsters! Your army's scattered. They thought you had fallen into their hands, and without you they were dismayed and panic-stricken when the monsters swept down on them.”

Zayin sat down on the rock, began to say something, and then stopped.

“Sergeant,” he said at last, “I was wrong to leave you. What have you been imagining in my absence?”

“No imagining, sir,” protested the sergeant. “There were monsters.”

Zayin heaved a deep sigh. “Tell me about these monsters, Sergeant,” he said resignedly. “And then tell me what happened to my men.”

“But, sir!” the sergeant protested, “they were the monsters you told us of. Four legs to run and leap on, and two arms to wield spears and bows with. Our men panicked and fled.”

Zayin held his head in his hands. “I, too, have seen, the monsters,” he said at last. “Indeed, I spent the night with them.” The sergeant's eyes became round. “In the morning,” Zayin continued, “I saw that they were horses. Mere animals like the ass, only bigger and swifter. One of them gave me a passing kick with its heels in the dark. But they can no more wield weapons than I can eat grass.”

The sergeant looked at him wildly. “Then perhaps, sir,” he exclaimed, “you can tell me how I came by this?” He bared his left arm, which had been roughly wrapped in his cloak, and showed Zayin the broken shaft of an arrow that was still imbedded in the flesh.

And at that moment, with his good arm, the sergeant seized his commanding officer and thrust him down behind the rock, flinging himself after him.

“Pardon, sir!” he gasped. “But there's another lot of 'em!” And he pointed to the valley floor.

Zayin looked down. Galloping apparently straight toward them was a party of four-footed creatures, brandishing bows and spears above human-looking heads. He sat paralyzed behind his rock. Could they climb perhaps, like mountain goats? Even fly? But no, they halted on the level ground beneath him. After all they had not been seen, for no eyes seemed to be directed toward them. He and the sergeant could escape up the hillside again. Keeping low, he twisted round and looked up the steep slope. But, as he looked, a figure appeared, outlined against the sky on a crag, almost immediately above him. Then another and another four-legged, two-armed figures with spears held ready. There was no going forward nor back for them, neither up nor down, and it was only a matter of time before they were seen on the stony hillside.

3

The Island of Giants

The voyage of Nun, the sailorâThe secrets of celestial navigationâPeople that lived on a volcanoâThe island of Thira and the myth of the buried Titans

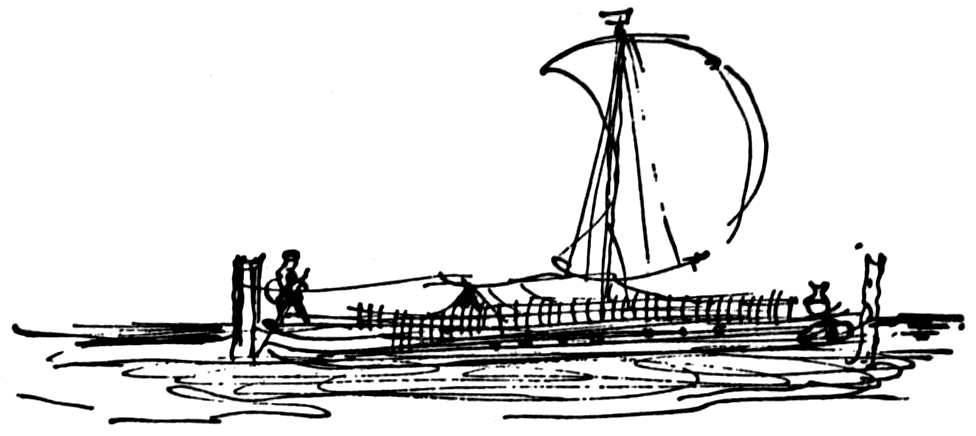

“Oars inboard!” ordered Nun, the sailor. “And hoist the sail!”

The mountains above Gebal were a black wall to the East in the early dawn. Inshore they had cut off the breeze, but the ship was far enough out to sea to catch it now, and the men were glad to pull in their heavy oars and stow them along the bulwarks. They manned the ropes that controlled the single great sail. With a rhythmic chant, following the commands of the boatswain, they heaved the halyard and the spar crept up the mast. The sheets were secured, the sailcloth filled with wind, and the heavy-laden ship, which had been wallowing gently in the swell, slowly gathered way through the blue water.

Nun, second son of Resh, the chief mason, and the youngest master mariner in the merchant fleet of Gebal, felt a sense of peace come over him, as it always did when he put to sea. All that could be done on shore had been done. The rigging had been checked and worn ropes replaced. The ship had been careened and the weed scraped from her bottom. The timbers had been sounded and the seams recaulked to keep her watertight. A new pair of eyes had even been painted on her bows. The cargo of cedar beams had been loaded aboard without any of them being dropped through the bottom. He had his passport, inscribed on stone in the name of the great King of Gebal, and the right sacrifices had been made for a fair wind.

The farewells on the quayside had perhaps been more affecting than usual, for his elder brother Zayin was absent on his expedition to the interior, his younger brother Aleph was overdue from his errand in the mountains, and he could see that his father and his sister Beth were torn to see the last of the brothers go, leaving them to their anxieties. But he had promised them a cheerful reunion soon, pushed out from the quayside, and now all that was behind him.

The wind was fair. Westward lay the islands. Cyprus they could hardly miss. It was Nun's custom on westbound passages to make the first crossing blind, though there were still shipmasters who thought it rash to go so far out of sight of land, and preferred to creep round the coast until they were north of the island and then strike south to make sure of hitting its longest coast. In this way you were hardly out of sight of land at allâbut once you had left a coast for good what guarantee was there that you would ever see it again, however correct your sacrifices had been?

But Nun's business lay farther west than Cyprus. It would be enough to have a sight of it to the northward to satisfy him that he was on course. Still, he would have to think of a haven for the night. It would be a pity to waste this good easterly breezeâhe was impatient at crawling over the face of the water under oarsâbut one could hardly stay at sea all night.

He looked away from the receding shore and saw his passenger standing beside him. In the distractions of clearing port and putting to sea, he had hardly had time to do more than formally welcome this stranger aboard, and since then he had forgotten about him. It was with an unpleasant feeling of surprise that he noticed him now. What Nun liked about being at sea was the freedom from interruption. No strangers to meet, no news good or bad until the next port. He was vexed now to think that he had with him this man of whom he knew nothing, and to whom he would have to be polite and guarded in his speech.

The passenger smiled pleasantly. “Are we making good time, Master?” he asked, speaking Nun's language carefully and correctly.

In a hurry? Nun wondered to himself. But perhaps the man was only making a polite remark. “We go with the wind, sir,” he answered. “We can't do better than that.”

“Your gods are kind to send us such a wind,” said the stranger.

“Goddess, actually, sir,” said Nun. “Yes, the Lady of Gebal is keeping her part of the bargain. Since there were no beasts or babies to sacrifice, we settled for a little gold figure I got last time in Crete. And we lugged a stone anchor up to the temple of the God of Battles, to keep him in mind of the navy. Those ought to buy us enough wind to take us there at least, and a bit of luck to keep us clear of enemies.”

“Ah!” said the passenger. “Let us hope we make good time then. I have an urgent appointment in Crete, or thereabouts.”

“Urgent appointment?” Nun repeated. “What kind of a creature is that? I've not heard it spoken before.”

“I mean I must be there by a certain time,” said the passenger. “That is why I took your ship. You have a reputation for swift voyages.”

“I don't like to waste time certainly,” said Nun, pleased by the compliment. “But as for appointments, and times that are certain, I've very little knowledge of them. The winds blow or they don't; the sea gives you a calm passage or holds you up with storms. All right, we make the best time we can, but there's never anything certain about it.”

“I speak of sun-time and star-time,” said the passenger. “These are always certain, for centuries ahead. We who watch the heavens in Chaldea know that in a short while certain stars and planets will meet. What this conjunction signifies is less certain, though we expect some great disaster. Nor do we know exactly where this will take place. My calculations lead me to the island of Crete, if Crete lies where they say it does: but it may be that when I get there I shall find it is not the place. I have already completed half my journey from Chaldea, and I trust you will let nothing delay me now. But since there is nothing interesting to see while the sun occupies the heavens, perhaps you will permit me to sleep.”

So saying the stranger wrapped himself in his robe and stretched himself out on the deck. Nun was puzzled and irritated. Who was this overbearing foreigner with his urgency and concern for the future? It was enough to spoil the pleasure of any voyageâhaving to get there by a certain time, and wondering what was going to happen when you did. A Chaldean, did he say he was? A priest, or a magician, or one of those astrologers, Nun supposed. The sort of person one went to sea to get away from. Nun felt like throwing him overboard to feed the fishes. If there was any trouble with storms or calms he would not hesitate long to do so; but at present all was going well and the stranger had impressed him to such an extent that Nun found himself giving orders in a low voice so as not to disturb his daytime sleep.

All day the east wind drove them on, and there was never even any need to make adjustment to the sail or the sheets. But as the sun sank toward the sea ahead of them, and Nun leaned on the steering oar and steered a little north of where it would disappear below the horizon, he could see that the crew were beginning to look anxiously around, and he could feel a slight anxiety beginning to form inside his own stomach. Darkness was coming, and still no sign of land. He had done this passage often enough before, but from Gebal to Cyprus was a good day's sail from dawn to dusk. He sent a man up to the masthead and told him to keep a good look-out on the starboard bow, and it was not long before the cry came, “Land ho!”

The passenger woke and got to his feet. “What land is this, Master?” he asked.

Nun was busy altering course toward the land by leaning on the steering oar and giving orders to adjust the pull of the sheets.” He answered the passenger's question shortly, “Cyprus.”

“Have you business in Cyprus, Master?” asked the passenger.

“No,” replied Nun, “we're buying no copper on this trip.”

“Why are we altering course, then?”

“It will soon be dark,” said Nun. “We must find a haven for the night.”

The man from the East looked at the heavens. “It will not be dark,” he said. “There is no cloud, and the stars will soon be out.”

“Starlight's no good to me,” said Nun. “I like to see where I'm going.”

The Chaldean came across the deck and stood close to Nun, putting his hand on the steering oar. “Listen,” he said. “I have traveled many nights across the desert already, under the stars. Why should we waste a night in haven when we have the open sea before us?”

Nun looked at him and thought for a while. Then he said, “When you are traveling across the desert in the dark there is little danger of falling into the sea. But if you strike land while you are crossing the sea it can be fatal. That's why we like to see where we are going.”

But the passenger continued to argue. “You have made this passage by day?”

“Yes,” replied Nun.

“Did you strike any land?”

“No.”

“If there is no land to run on to by day, why should there be any by night?” the stranger went on persuasively.

“It's all very well for a landsman to talk,” retorted Nun. “You don't know how confusing the sea can be at night, with the sea sprites flashing their lights in every wave and all those nameless stars spinning above your head.”

The stranger put his hand over Nun's on the steering oar and looked deep into his eyes. “Captain,” he said, “would you learn secrets unknown to any other shipmaster? Would you not like to be at home on the sea by night as well as by day? The stars are not nameless; each one has his place and direction. Sail with me tonight and other nights, and I will teach you the names of the stars and the constellations, and tell you how they can guide you.”

No man had ever laid hands on the steering oar when Nun was manning it, and few had ever argued a point of navigation with him since he had become master of a ship. Now is the time to throw this interfering stranger to the fishes, Nun thought. And yet he did not even feel anger rising inside him, and he wondered why. I should assert myself as captain, he told himself. What would the crew think? And yet, what was it that made the crew respect him? Could he pull an oar better than the oarsmen? No. Could he splice a rope better than the seamen? No. Was it because he could curse them and keep them in order? Not even that, for the boatswain could curse much more fluently than his captain. No, it was because he knew where they were going. He had the whole voyage, out and backâthe gods willingâplanned in his head. The crew respected Nun for it, and Nun could not help respecting this stranger who seemed to carry in his head not merely landmarks of a voyage but also signs in the heavens to guide him. It might be something worth learning.

Without a word, Nun let the steering oar move over to starboard under the pressure of the stranger's hand, and the ship's head turned slowly away from the land and toward the open sea and the setting sun.

He saw the startled and outraged looks on the faces of the crew, but spoke to them casually. “What's the matter, then? You've slept all day, while the wind's done the work. Let's see if you can sleep as well by night. I only need half of you to keep company with me and the stars. Boatswain, the oarsmen on the starboard side can keep the first watch.” And there was enough confidence in his voice to make the men move obediently to their look-out positions as ordered by the boatswain, though not without some muttering.

“No shore tonight?” he heard them remark. “The Old Man off his head, then?”

Nun did not feel as confident as he hoped he sounded, but part of him felt a surge of excitement at the prospect of the night passage.

The sun sank on to the horizon ahead of the ship, and as it did so it seemed in the haze to lose its roundness and collapse like a pricked bladder. The sailors watched it with long faces. Would they ever see it again in its proper shape, or would they reach the edge of the world in the darkness and be poured over it into nothingness? The last red spark showed above the sea, turned suddenly bright green, and sank. The sailors' hearts seemed to sink with it. But Nun's eyes were already on the zenith, the highest part of the sky where the stars were beginning to appear, and on the darkening eastern sky astern of the ship.

“Tell me!” said Nun impatiently. “What is the name of that one? And that one, and the bright one alone by itself there?”

“Have patience!” said the Chaldean calmly. “We shall see them all together soon. Those you see now will not help you with your voyaging, for they are wanderers too, every night in a different part of the sky. It needs many years of study to learn their paths.”

The east wind drove them on, and darkness came quickly. Soon the whole sky was aglitter with stars, and Nun craned his neck and stared as if he had never seen them before. “I shall never know all their names!” he sighed.

“Patience!” said the stranger again. “If a man lived a thousand years and never slept by night, he would still leave many stars unnamed. Learn them by their groups first, their constellations. First of all tell your steersman to steer by that bright group that is now above the horizon. That you may call the Lesser Dog, and it will lead you west for a while until it sinks below the sea. Now look to the North. There is the Great Bear, who is always with us, and the Little Bear, in whose tail sits the North Star, the only one that stays still in the firmament. If you want to steer north at any time, that is your mark.”