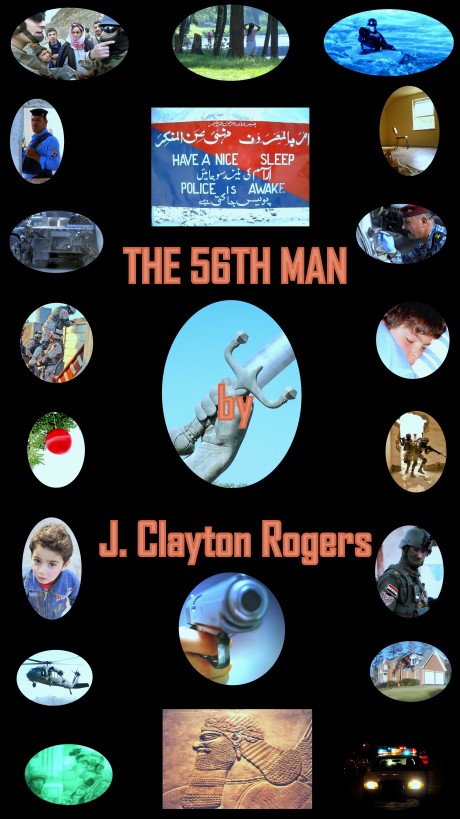

The 56th Man

Authors: J. Clayton Rogers

Tags: #terrorism, #iraq war, #mystery suspense, #adventure abroad, #detective mystery novels, #mystery action, #military action adventure, #war action adventure, #mystery action adventure, #detective and mystery

THE 56TH MAN

By J. Clayton Rogers

Smashwords Edition

Copyright 2009

ONE

Baghdad, March 27, 2003

The storm receded in the distance, as all

storms did. The boy was protected, even coddled. He did not

comprehend that this storm, like all the others over the last week,

was unseasonal. But he knew few things this thunderous ended

abruptly. They faded off, as though the events themselves were

aware of their majesty and were reluctant to end the proceedings.

Like his father's wrath, which tended to decline into dark

mutterings. There was no specific end to his anger; only when a

tentative smile flickered across his stern face did the boy know

that sweet reason was finally breaking through, however slowly.

But his father was not here now, nor his big

brother. They had both been wearing uniforms when they left,

leaving him and the middle brother and their mother to huddle in

the basement while the storm broke overhead. The biggest storm the

boy had ever experienced, big enough to shudder their bones and

draw low cries of fear from their compressed lips. It would have

been reassuring if his father had been with them. The boy would not

have even minded if his father had cried out with the rest of

them--though such a reaction was unlikely.

But now the storm was receding and the boy

grew fidgety. He tried to pull away from his mother, who kept him

in place with a strong hand.

"

Qasim,

"

she commanded her

middle son.

"

Go up and see.

And be careful!

"

The younger boy fumed as his brother went

upstairs. He was more unwilling than unable to understand why he

should not take charge of his own destiny.

"

Ummi,

"

he complained,

squirming.

His mother’s grip

tightened.

"

B

e still!

"

She hearkened to her middle son‘s footsteps

overhead. Her mind had become a listening post, her dread a

trembling sentry.

The boy hated the cramped basement, so full

of family treasures that there was scarcely room for the three of

them. Was that why his father and eldest brother had left? Because

they would not have been able to squeeze themselves between the

antique vases and statuary that they had moved downstairs

throughout the previous week? And what was in those crates over in

the corner? They had been unloaded from army trucks and carried

here by soldiers who had brushed aside his parents' protests with

curious indifference. Other men in uniform were highly deferential

to the boy's father. But not these. This lack of respect bothered

the youngest son. The soldiers laughed idiotically when he openly

snubbed them. After they left, the boy was threatened with severe

punishment if he went near the crates.

And now they were not ten feet away from

him.

The boy stopped

fidgeting.

"

Ummi, I don’t

hear--

"

The door at the top of the stairs.

"

You can come

up, now,

"

Qasim called to

them.

"

They’re gone, for

now.

"

Still holding his hand, the boy's mother

rose, lifting him to his feet, and led him up.

"

Aoothoo

billahi meen ash-shaytan ar-rajeem,

"

the boy's mother murmured. The boy was startled.

She was asking for Allah's protection against the accursed Satan.

Not typical language in this household.

The boy was intrigued by glass strewn across

the front room. Where had it come from? Ah...the picture window.

Smashed to smithereens! If he had done that...kicked his ball the

wrong way while playing in the yard...he would have feared for his

very life. But there was no one here to punish. It seemed to have

exploded all by itself, on its very own. How could such a thing

happen?

"

That's the

only damage, Subhan Allah,

"

said Qasim.

"

We're very

lucky.

"

"

Lucky!

"

his mother

scoffed.

"

This is punishment.

No one else has a window like this, where everyone can see in.

Lucky!

"

She paused, looking

lost as she stared at the vacant window.

"

It's your father's...he never went

to the mosque...mocked the imam's...he was never a believer...he

never bowed his head... Astaghfirullah. Astaghfirullah.

Astaghfirullah...

"

I ask Allah forgiveness. This was something

you said when you feared going to Jahannam, Hell. And an especially

horrible fate awaited unbelievers, who would not be rescued from

their torments on Judgment Day: Qiyamat.

She seemed to the boy to be saying that, one

way or another, they would all spend eternity eating Zaqqum thorns,

and they had Baba to blame for it. Were things really that bad?

Wanting to judge this gloomy assessment for himself, the boy

strained towards the back door. Certainly, his mother would not

mind if he went out that way, with a high wall and locked gate for

protection. But she held onto him. He considered the practicality

of a tantrum. After all, his father wasn't here.

"

Get your

father on the phone!

"

"

The phones

aren't working,

"

Qasim

reasoned with his mother. The boy watched his brother's Adam's

apple shuttle up and down his throat as he confronted an adversary

far more tenacious than the manmade storms.

"

He has a

radio, doesn't he? Call him!

"

Qasim walked across the broken glass to a

small charger on a side table.

"

The power's

been off. It may not be charged. The enemy is

jamming--

"

"

Find

out!

"

The middle son took the radio out of its

cradle and tested the transmission button. There was a burst of

static, then a smooth electric sound. He pressed the button again

and spoke. He released the button. A moment later a man's voice

came on. It didn't sound like the boy's father, but it was fuzzy.

Hard to say. In her excitement, the boy's mother let go of him and

raced across the room.

"

Careful!

"

Qasim cautioned

his mother.

"

Careful! It's not

a toy!

"

The middle son assumed the authority of an

adult as he explained to his mother how to operate the radio. She

stopped her frantic efforts to grab it out of his hand and listened

with a show of patience, as though heeding a grown man.

The boy skipped out the back door. He was a

man, too. Independent. He hopped down the steps and stopped,

listening.

The walled garden seemed undisturbed by the

storm--except for some unripe fruit that had fallen off the

tamarind tree that spread its shade over the far corner. The boy's

mother would not be pleased by that. He had once clambered up a

ladder and picked some of the fruit too early in the year. His

intent was to be helpful, but his mother had berated him for the

waste. The fruit was useless until it dangled in long, plump

strands.

Beyond the wall pillars of smoke rose in all

directions. The outside world had been churned into noisy chaos.

Shouting, cries of horror, pain and astonishment. The boy thought

he recognized some of the voices. Could these be his neighbors? He

could not say for certain. There was a high pitch in their tone

that carried the voices just beyond familiarity. And there were

screams. Who could be screaming? It was confusing. The fruit had

incontinently fallen, but everything else in the garden was

judiciously serene. The boy felt safe, as though snuggled in a

nest.

He went to the gate and peered through the

bars. People were running back and forth, blindly breaking through

thick feathers of smoke. They were throwing up their hands or

shaking their fists at the sky. Was the sky the enemy? Had the sky

broken the picture window? The boy glanced up. The air directly

above the garden showed only a faint trace of smoke. But the smell

was strong. He looked out again. Further up the street the haze was

impenetrable. A man emerged suddenly out of the smoke, like a genie

popping out of his bottle. He rubbed his eyes, then gazed about

numbly, as if waking from a long nap.

The boy saw nothing aimless about the people

dashing back and forth in the street. They were vibrant, and in his

small lexicon of life vibrancy spelt purpose. Even moaning, like

the woman who stumbled and fell to the curb, was a kind of

decisiveness. She was doing something...even if he could not begin

to understand what it was.

Backing away from the gate, the boy stopped

midway up the path of slate flagstones and surveyed the garden.

Wasn't there something he could do? Some way that he could be

useful?

The opportunity was under his nose. Of

course! He would pick up the fallen tamarind fruit. That would

certainly please his father and mother. Even when ripe, they never

ate it. His father bemoaned the annual mess and the insects the

rotting fruit attracted after it had fallen to the ground. Planted

long ago by the previous owner of the house, the tree was intended

to provide shade, not sustenance. The tamarind fruit the boy's

family ate came from India, in a variety of forms. When his mother

stormed at him last year for picking unripe buds, she must have

been more concerned about the height of the ladder than the loss of

foodstuff.

Dragging a reed basket out of the flowerbed,

he set to work. As he gathered the fruit, he noticed some branches

that had broken loose. Most of them were small, yet still too large

for the basket. How should he deal with them? Pile them next to the

path, perhaps, so that the gardener could scoop them up for

disposal? That seemed an excellent solution. The boy was sure his

father would approve.

But after several minutes spent dragging

branches across the yard the true magnitude of the job revealed

itself to him. There was more here than he had realized. And some

of the branches were much heavier than he'd anticipated. He

abandoned the pile at the base of the patio steps and returned to

his original task. Let the gardener deal with the branches. The

fruit was much smaller and easier to handle.

And yet, after several minutes of bending and

standing, it struck him this chore was just as tiresome as dragging

tree branches. He'd never known the unripened fruit to fall in such

abundance. What could have caused it? He raised his eyes to the

tamarind limbs overhead. The tree looked shaggy, weather-beaten.

Well, that only made sense after a storm. Especially after a storm

that could shatter a picture window into a thousand fragments.

There was something stuck in the lowest fork

of the tree. It looked like string or tape. Walking around to the

other side, between the wall and the tree, he could make out a

knob-like thing, brightly colored. Somebody's toy had been tossed

by the storm from who knew where, until it had fetched up here.

From what he could judge, the knob was about the size of his fist.

The boy glanced about for the gardener's ladder, then paused. The

last time he had dragged the ladder against the tree his mother had

come roaring out like a dragon in a fairytale. It would be best not

to draw attention.

He searched the garden and found a plastic

crate behind the mulch pile. The bottom was latticed. He had seen

the gardener use it to sift out stones and roots before casting

soil and mulch on the flowerbed. It was strong, but light. Carrying

it over to the tree, the boy upended the crate and planted it on

the garden side of the tree. He would catch hold of the tape and

drag the knobby thing down by the tail.

The tape was about six inches long and

flapped temptingly against the tree as the boy stood on the crate

and stretched up.

Just out of reach.

The boy sighed, looked down for a moment,

then raised his head, held out his right arm as far as it would go,

and gave a little jump.

Missed.

Instead of being frustrated, he was egged on

by failure. He even found it amusing to miss, and began to laugh so

hard that it robbed his legs of strength. His jumps failed by an

inch, then several inches. He even fell off the crate once, still

laughing.