The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less (23 page)

Read The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less Online

Authors: Richard Koch

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Psychology, #Self Help, #Business, #Philosophy

• The 80/20 Principle treats time as a friend, not an enemy. Time gone is not time lost. Time will always come round again. This is why there are seven days in a week, twelve months in a year, why the seasons come round again. Insight and value are likely to come from placing ourselves in a comfortable, relaxed, and collaborative position toward time. It is our use of time, and not time itself, that is the enemy.

• The 80/20 Principle says that we should act less. Action drives out thought. It is because we have so much time that we squander it. The most productive time on a project is usually the last 20 percent, simply because the work has to be completed before a deadline. Productivity on most projects could be doubled simply by halving the amount of time for their completion. This is not evidence that time is in short supply.

TIME IS THE BENIGN LINK BETWEEN THE PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE

It is not shortage of time that should worry us, but the tendency for the majority of time to be spent in low-quality ways. Speeding up or being more “efficient” with our use of time will not help us; indeed, such ways of thinking are more the problem than the solution.

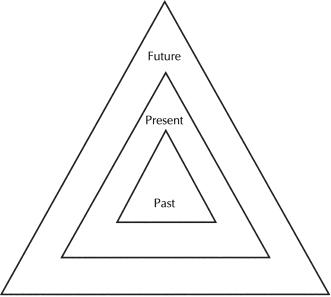

80/20 Thinking directs us to a more “eastern” view of time. Time should not be seen as a sequence, running from left to right as in nearly all graphical representations that the culture of business has imposed on us. It is better to view time as a synchronizing and cyclical device, just as the inventors of the clock intended. Time keeps coming round, bringing with it the opportunity to learn, to deepen a few valued relationships, to produce a better product or outcome, and to add more value to life. We do not exist just in the present; we spring from the past and have a treasure trove of past associations; and our future, like our past, is already immanent in the present. A far better graphical representation of time in our lives than the left-to-right graph is a series of interlocked and ever larger and higher triangles, as shown in Figure 35.

The effect of thinking about time in this way is that it highlights the need to carry with us, through our lives, the most precious and valued 20 percent of what we have—our personality, abilities, friendships, and even our physical assets—and ensure that they are nurtured, developed, extended, and deepened, to increase our effectiveness, value, and happiness. This can only be done by having consistent and continuous relationships, founded on optimism that the future will be better than the present, because we can take and extend the best 20 percent from the past and the present to create that better future. Viewed in this way, the future is not a random movie that we are halfway through, aware of (and terrified by) time whizzing past. Rather, the future is a dimension of the present and the past, giving us the opportunity to create something better. 80/20 Thinking insists that this is always possible. All we have to do is to give freer rein and better direction to our most positive 20 percent.

Figure 35 The time triad

A PRIMER FOR TIME REVOLUTIONARIES

Here are seven steps to detonating a time revolution.

Make the difficult mental leap of dissociating effort and reward

The Protestant work ethic is so deeply engrained in everyone, of all religions and none, that we need to make a conscious effort to extirpate it. The trouble is that we do enjoy hard work, or at least the feeling of virtue that comes from having done it. What we must do is to plant firmly in our minds that hard work, especially for somebody else, is not an efficient way to achieve what we want. Hard work leads to low returns. Insight and doing what we ourselves want lead to high returns.

Decide on your own patron saints of productive laziness. Mine are Ronald Reagan and Warren Buffett. Reagan made an effortless progression from B-film actor to darling of the Republican Right, governor of California, and extremely successful president.

What did Reagan have going for him? Good looks, a wonderfully mellifluous voice which he deployed instinctively on all the right occasions (the high point of which undoubtedly consisted in his words to Nancy when shot, “Honey, I forgot to duck”), some very astute campaign managers, old-fashioned grace, and a Disneyesque view of America and the world. Reagan’s ability to apply himself was limited at best, his grasp of conventional reality ever more tenuous, his ability to inspire the United States and destroy communism ever more awesome. To maul Churchill’s dictum, never was so much achieved by so few with so little effort.

Warren Buffett became (for a time) the richest man in the United States, not by working but by investing. Starting with very little capital, he has compounded it over many years at rates far above stock market average appreciation. He has done this with a limited degree of analysis (he started before slide rules were invented) but basically with a few insights which he has applied consistently.

Buffett started his riches rollercoaster with one Big Idea: that U.S. local newspapers had a local monopoly that constituted the most perfect business franchise. This simple idea made him his first fortune, and much of his subsequent money has been made in shares in the media: an industry he understands.

If not lazy, Buffett is very economical with his energy. Whereas most fund managers buy lots of stocks and churn them frequently, Buffett buys few and holds them for ages. This means that there is very little work to do. He pours scorn on the conventional view of investment portfolio diversification, which he has dubbed the Noah’s Ark method: “one buys two of everything and ends up with a zoo.” His own investment philosophy “borders on lethargy.”

Whenever I am tempted to do too much, I remember Ronald Reagan and Warren Buffett. You should think of your own examples, of people you know personally or those in the public eye, who exemplify productive inertia. Think about them often.

Give up guilt

Giving up guilt is clearly related to the dangers of excessively hard work. But it is also related to doing the things you enjoy. There is nothing wrong with that. There is no value in doing things you don’t enjoy.

Do the things that you like doing. Make them your job. Make your job them. Nearly everyone who has become rich has had the added bonus of becoming rich doing things they enjoy. This might be taken as yet another example of the universe’s 80/20 perversity.

Twenty percent of people not only enjoy 80 percent of wealth but also monopolize 80 percent of the enjoyment to be had from work: and they are the same 20 percent!

That curmudgeonly old Puritan John Kenneth Galbraith has drawn attention to a fundamental unfairness in the world of work. The middle classes not only get paid more for their work, but they have more interesting work and enjoy it more. They have secretaries, assistants, first-class travel, luxurious hotels, and more interesting working lives too. In fact, you would need to have a large private fortune to afford all the perquisites that senior industrialists now routinely award themselves.

Galbraith has advanced the revolutionary view that those who have less interesting jobs should be paid more than those with jobs that are more fun. What a spoilsport! Such views are thought provoking, but no good will come of them. As with so many 80/20 phenomena, if you look beneath the surface you can detect a deeper logic behind the apparent inequity.

In this case the logic is very simple. Those who achieve the most have to enjoy what they do. It is only by fulfilling oneself that anything of extraordinary value can be created. Think, for example, of any great artist in any sphere. The quality and quantity of the output are stunning. Van Gogh never stopped. Picasso ran an art factory long before Andy Warhol, because he loved what he did.

Revel in Michelangelo’s prodigious, sexually driven, sublime output. Even the fragments that I can remember—his

David, The Dying Slave,

the Laurentian Library, the New Sacristy, the Sistine chapel ceiling, the Pietà in Saint Peter’s—are miraculous for one individual. Michelangelo did it all, not because it was his job, or because he feared the irascible Pope Julius II or even to make money, but because he loved his creations and young men.

You may not have quite the same drives, but you will not create anything of enduring value unless you love creating it. This applies as much to purely personal as to business matters.

I am not advocating perpetual laziness. Work is a natural activity that satisfies an intrinsic need, as the unemployed, retired, and those who make overnight fortunes rapidly discover. Everyone has their own natural balance, rhythm, and optimal work/play mix and most people can sense innately when they are being too lazy or industrious. 80/20 Thinking is most valuable in encouraging people to pursue high-value/satisfaction activities in both work and play periods, rather than in stimulating an exchange of work for play. But I suspect that most people try too hard at the wrong things. The modern world would greatly benefit if a lower quantity of work led to a greater profusion of creativity and intelligence. If much greater work would benefit the most idle 20 percent of our people, much less work would benefit the hardest-working 20 percent; and such arbitrage would benefit society both ways. The quantity of work is much less important than its quality, and its quality depends on self-direction.

Free yourself from obligations imposed by others

It is a fair bet that when 80 percent of time yields 20 percent of results, that 80 percent is undertaken at the behest of others.

It is increasingly apparent that the whole idea of working directly for someone else, of having a job with security but limited discretion, has just been a transient phase (albeit one lasting two centuries) in the history of work.

4

Even if you work for a large corporation, you should think of yourself as an independent business, working for yourself, despite being on Monolith Inc.’s payroll.

The 80/20 Principle shows time and time again that the 20 percent who achieve the most either work for themselves or behave as if they do.

The same idea applies outside work. It is very difficult to make good use of your time if you don’t control it. (It is actually quite difficult even if you do, since your mind is prisoner to guilt, convention, and other externally imposed views of what you should do—but at least you stand a chance of cutting these down to size.)

It is impossible, and even undesirable, to take my advice too far. You will always have some obligations to others and these can be extremely useful from your perspective. Even the entrepreneur is not really a lone wolf, answerable to no one. He or she has partners, employees, alliances, and a network of contacts, from whom nothing can be expected if nothing is given. The point is to choose your partners and obligations extremely selectively and with great care.

Be unconventional and eccentric in your use of time

You are unlikely to spend the most valuable 20 percent of your time in being a good soldier, in doing what is expected of you, in attending the meetings that everyone assumes you will, in doing what most of your peers do, or in otherwise observing the social conventions of your role. In fact, you should question whether any of these things is necessary.

You will not escape from the tyranny of 80/20—the likelihood that 80 percent of your time is spent on low-priority activities—by adopting conventional behavior or solutions.

A good exercise is to work out the most unconventional or eccentric ways in which you could spend your time: how far you could deviate from the norm without being thrown out of your world. Not all eccentric ways of spending time will multiply your effectiveness, but some or at least one of them could. Draw up several scenarios and adopt the one that allows you the most time on high-value activities that you enjoy.

Who among your acquaintances is both effective and eccentric? Find out how they spend their time and how it deviates from the norm. You may want to copy some of the things they do and don’t do.

Identify the 20 percent that gives you 80 percent

About a fifth of your time is likely to give you four-fifths of your achievement or results and four-fifths of your happiness. Since this may not be the same fifth (although there is usually considerable overlap), the first thing to do is to be clear about whether your objective, for the purposes of each run through, is achievement or happiness. I recommend that you look at them both separately.