The a to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers (28 page)

Read The a to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers Online

Authors: Harold Schechter

Tags: #True Crime, #General

“A Visit from Old Ed”

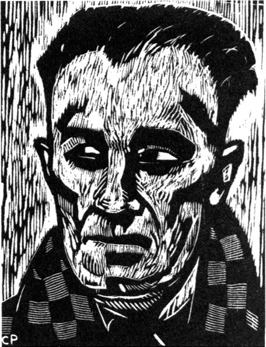

Woodcut portrait of Ed Gein by Chris Pelletiere

Sick jokes about Ed

Gein

weren’t the only kind of black humor circulating in the months following the discovery of his crimes. Researching local reaction to Gein’s atrocities, psychologist George Arndt recorded this ghoulish parody of Clement Moore’s “A Visit from St. Nicholas”:

’Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the shed,

All creatures were stirring, even old Ed.

The bodies were hung from the rafters above,

While Eddie was searching for another new love.

He went to Wautoma for a Plainfield deal,

Looking for love and also a meal.

When what to his hungry eyes should appear,

But old Mary Hogan in her new red brassiere.

Her cheeks were like roses when kissed by the sun.

And she let out a scream at the sight of Ed’s gun.

Old Ed pulled the trigger and Mary fell dead,

He took his old axe and cut off her head.

He then took his hacksaw and cut her in two,

One half for hamburger, the other for stew.

And laying a hand aside of her heel,

Up to the rafters went his next meal.

He sprang to his truck, to the graveyard he flew,

The hours were short and much work must he do.

He looked for the grave where the fattest one laid,

And started in digging with shovel and spade.

He shoveled and shoveled and shoveled some more,

Till finally he reached the old coffin door.

He took out a crowbar and pried open the box,

He was not only clever but sly as a fox.

As he picked up the body and cut off her head,

He could tell by the smell that the old girl was dead.

He filled in the grave by the moonlight above,

And once more old Ed had found a new love.

“He had a bizarre sense of humor.”

One of Jeffrey Dahmer’s former schoolmates

J

UVENILES

Little boys who grow up to be serial killers tend to be extremely sadistic, but the targets of their cruelty are almost always small animals, not other children (see

Animal Torture

). An exception to this rule was the juvenile psychopath Jesse Pomeroy, one of the most unsettling criminals of nineteenth-century America.

Pomeroy suffered a difficult boyhood. He was raised in hardship by a widowed mother, who scraped together a meager living as a seamstress in South Boston. And he was cursed with a grotesque appearance—his mouth was disfigured by a harelip, and one eye was covered with a ghastly white film. Still, his contemporaries weren’t inclined to attribute his atrocities to childhood trauma. To them, he was simply a natural-born fiend.

Little is known about Pomeroy’s early life until he reached the age of

eleven—at which point, he began preying on other children. Between the winter of 1871 and the following fall, he attacked seven little boys, luring them to a secluded spot, then stripping, binding, and torturing them. His first victims were subjected to savage beatings. Later, Pomeroy took to slashing his victims with a pocketknife or stabbing them with needles.

Arrested at the end of 1872, Pomeroy was sentenced to ten years in a reformatory but managed to win probation after only eighteen months by putting on a convincing show of rehabilitation. No sooner had he been released, however, than he reverted to his former ways. But by this time, the teenage psychopath wasn’t content merely to inflict injury. At this point, he was homicidal.

In March 1874 he kidnapped ten-year-old Mary Curran, then mutilated and killed her. A month later, he abducted four-year-old Horace Mullen, took him to a remote stretch of marshland, and slashed him so savagely with a pocketknife that the boy was nearly decapitated.

When Mullen’s body was found, suspicion immediately lighted on Pomeroy, who was picked up with the bloody weapon in his pocket and mud on his boots that matched the soggy ground of the murder site. When police showed Pomeroy the victim’s horribly mutilated body and asked if he had killed the little boy, Pomeroy simply said, “I suppose I did.” It wasn’t until July that Mary Curran’s corpse was found, when laborers uncovered her decomposed remains while excavating the earthen cellar of the Pomeroys’ house.

Pomeroy’s 1874 trial was a nationwide sensation. Moral reformers blamed his crimes on the lurid “dime novels” of the day (very much like those modern-day bluenoses who attribute the current crime rate to gangsta rap and violent videogames). Unfortunately, their position was undermined by Pomeroy’s insistence that he had never read a book in his life.

In spite of his age, Pomeroy was condemned to death, but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment with a harsh proviso: the so-called boy-fiend would serve out his sentence in solitary. And indeed, it wasn’t until forty-one years later that he was finally allowed limited contact with other inmates. He died in confinement in 1932, at the age of seventy-two.

Pomeroy makes a brief but memorable appearance in Caleb Carr’s bestselling 1994 novel,

The Alienist,

when the titular hero—seeking insight into the mind of an unknown serial killer—travels to Sing Sing to interview the former boy-fiend and finds him locked in a punishment cell, his head encased in a cagelike “collar cap.”

During the late 1990s—a century after Pomeroy’s crimes—America was shocked by a rash of horrendous killings committed by juvenile sociopaths. In Pearl, Mississippi, sixteen-year-old Luke Woodham killed three schoolmates and wounded seven others after knifing his own mother to death. In West Paducah, Kentucky, fourteen-year-old Michael Carneal gunned down three fellow students and wounded five others at an early-morning prayer meeting. In Springfield, Oregon, fifteen-year-old Kip Kinkel murdered his parents, then shot twenty-seven students, killing two. In Jonesboro, Arkansas, Andrew Golden and Mitchell Johnson—ages eleven and thirteen—set off a fire alarm to draw their classmates outside, then opened fire, killing four students and a teacher.

The most notorious of these incidents occurred in April 1999, when seventeen-year-old Dylan Klebold and eighteen-year-old Eric Harris massacred their schoolmates and teachers at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, leaving thirteen dead and twenty-five wounded. Like others of their ilk, however, Klebold and Harris were not serial killers but

Mass Murderers

:

suicidal rampage killers so full of rage and despair that they chose to end their own lives after inflicting a terrible vengeance on the world they had come to find unbearable.

“Despite both the shackles on the collar cap, Jesse had a book in his hand and was quietly reading. . . . ‘Pretty hard to get an education in this place,’ Jesse said, after the door had closed. ‘But I’m trying. I figure maybe that’s where I went wrong—no education. . . ’ ” “Laszlo nodded. ‘Admirable. I see you’re wearing a collar cap.’

“Jesse laughed. ‘Ahh—-they

claim

I burned a guy’s face with a cigarette while he was sleeping. . . . But I ask you—’ He turned my way, the milky eye floating aimlessly in his head. ‘Does that sound like me?’ “

From Caleb Carr’s

The Alienist

Edmund Kemper

In August 1963, when Edmund Kemper was fifteen years old, he stepped up behind his grandmother and casually shot her in the back of the head. After stabbing her a few times for good measure, he calmly waited for his grandfather to return from work, then gunned him down, too. His motive? “I just wondered how it would feel to shoot Grandma,” he explained to the police.