The Aeneid (61 page)

Authors: Virgil

Scipios

: Scipio Africanus Maior defeated Hannibal at Zama in 202

BC

. Scipio Africanus Minor destroyed Carthage in 146

BC

.

Fabricius

: Gaius Fabricius Luscinus fought against Pyrrhus, king of Epirus, in 80–79

BC

. The power he found in poverty is an allusion to his rejection of Pyrrhus’ gifts.

Serranus

: Gaius Atilius Regulus was sowing seed (

serere

: to sow) on his farm when he was called to the consulship in 257

BC

. He therefore acquired the name Serranus.

Fabii

: Anchises at 6.845 calls out to his friends the members of the great Fabian family to ask why they are all in such a hurry to reach the light of life that they are hustling one weary spirit along with them, and then he realizes that the problem is not weariness. This is the great Q. Fabius Maximus Cunctator (

cunctator

: delayer) who used Fabian tactics against Hannibal in 217–216

BC

in the Second Punic War. He is not tired. It is his nature to delay!

Marcellus

: M. Claudius Marcellus, consul five times, killed the Gaulish chieftain Viridomarus in single combat in 222

BC

, thus becoming the third Roman, after Romulus and Cossus, to win the Supreme Spoils (

Spolia Opima

). Augustus was eager to make sure that there would not be a fourth (see Livy 4.20.5). The younger M. Claudius Marcellus (42–23

BC

) was the son of Augustus’ sister Octavia, and was adopted by Augustus in 25

BC

. An ancient life of Virgil (

Vita Donati

32) describes how, when Virgil was reading this passage to Octavia and Augustus, Octavia swooned when he reached line 882.

(Book 8, lines 626–728)

Most of the scenes on the shield are incidents from Italian wars (see lines 626 and 678), all depicted with vivid evocation of the colours, textures and materials used in this imaginary work of art and the sounds evoked by it.

Around the outside of the circle are six scenes described in forty-one lines:

(i)

The wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, who are to found the city in 753

BC

.

(ii)

The rape of the Sabine women as planned by Romulus and the subsequent war and reconciliation.

(iii)

The punishment of Mettus Fufetius, dictator of Alba Longa who will make a treaty with Tullus Hostilius, king of Rome 673–642

BC

, and then desert him in battle.

(iv)

Two famous scenes from the Etruscan attack on Rome in 508

BC

.

(v)

At the top of the shield the attack of the Gauls in 390

BC

and the origin of some traditional features of Roman religion. The matrons of Rome were permitted to drive in carriages to the games and temples in return for giving their gold and jewels to enable Camillus to build a temple to Apollo after the defeat of Veii in 396

BC

.

(vi)

Presumably at the bottom of the shield, scenes in the Underworld showing Catiline whose conspiracy was put down by Cicero in 63

BC

and M. Porcius Cato who fought for the Republican cause against Caesar and committed suicide after his defeat at Thapsus in 46

BC

. Like his great ancestor Cato the Elder (6.841) he was regarded as a model of the uncompromising Republican virtues.

In the centre of the shield, in a ring of silver dolphins feathering with white foam the silver sea and its golden waves, is depicted Augustus’ victory over Antony and Cleopatra at Actium in 31

BC

and his triple triumph of 29

BC

(Dalmatian, Actian and Alexandrian). To this Augustan theme Virgil devotes fifty-four lines.

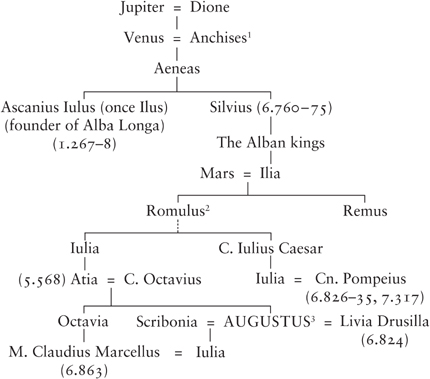

THE JULIAN FAMILY

1. Anchises’ grandfather Assaracus seems to be mentioned in a Julian connection at 1.284, 6.778, 9.259, 643.

2. This gap is variously filled (see S. Weinstock,

Divus Julius

, p. 183 n. I.).

3. Augustus was born C. Octavius in 63

BC

. He was adopted as Julius Caesar’s son by Caesar’s will in 44

BC

under the name of C. Iulius Caesar Octavianus (called Octavian in English), and took the name of Augustus in January 27

BC

.

Rome during the reign of Augustus

I started to compile a glossary of mythological terms in the

Aeneid

, but soon decided that it was not necessary. Such is Virgil’s command of narration that the poem usually explains itself as it goes along. Where this is not so, explanations have been added to the text, for example at the beginning of Book 6 where there is an unusual concentration of such difficulties. Here, the modern reader needs to be told that the Chalcidian citadel is the Chalcidian colony of Cumae; that Phoebus in line 18 is the same god as Apollo in line 9; that Androgeos was the son of Minos and that the Athenians were held to be the descendants of Cecrops. The

Aeneid

is first and foremost a narrative, and narratives do not thrive on interruptions. A glossary would drive readers to the end of the book. Even footnotes would take the eye to the foot of the page and the mind to scholarly furniture. It is a regrettable interference with the text of Virgil, but I have preferred to add such information to the body of the work where it is necessary rather than check the flow of the narrative.

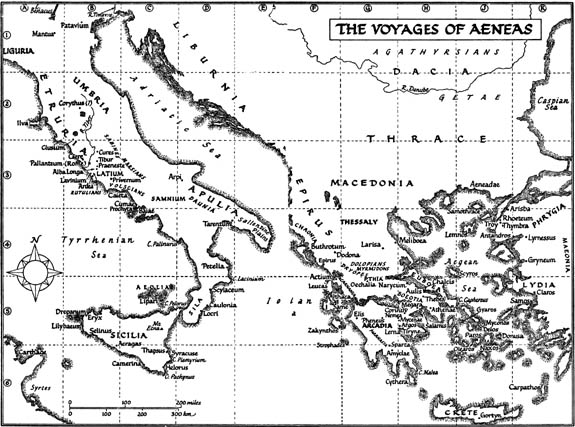

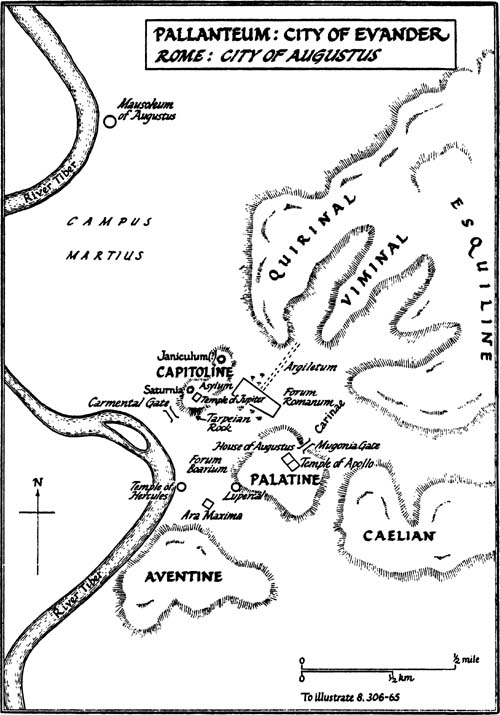

Geography is another matter. The ancients knew their Mediterranean world better than we do. I have therefore supplied maps and an index which are meant to give topographical information which may be helpful for understanding the poem. These therefore omit peoples and places whose locality is sufficiently indicated by the context, for example the lists of the Latin enemies of Aeneas at the end of Book 7 and his Etruscan allies at 10.163–214.

Virgil has many equivalent or nearly equivalent geographical terms at his disposal. Greeks are called Achaeans, Argives, Graians, and Pelasgians; Troy is Dardania; Ilium, Pergamum (strictly its citadel), and its people are Phrygians, Teucrians, even Laomedontiadae, as well as Trojans; Etruscans are also Lydians, Tuscans and Tyrrhenians. Where Virgil seems to be using these terms purely for metrical convenience, the translation speaks of Greeks, Trojans and Etruscans. But the variants are preserved where they are used to some effect, rhetorical at 2.324–6, for example, or emotive (the term ‘Phrygian’ usually carries a contemptuous allusion to the alleged effeminacy of the Trojans). In particular Italy is variously referred to as Ausonia, Oenotria, Hesperia (the Western Land), and sometimes these terms are used in prophecies not understood by those who hear them. This oracular obscurity is preserved in the translation since the progressive revelation of the divine will is an important aspect of the plot of the poem. The Tiber, for instance, is called the Lydian Thybris at 2.781–2 and Aeneas can

have no idea what is meant. The Italian river is always referred to by this Greek form of its name until 6.873.

In the index these equivalents will be noted but they will not occur on the maps. So too rivers and mountains appear in the list, but normally not on the maps.

Names in brackets do not appear on the maps; names with map references appear on the map ‘The Voyages of Aeneas’; other names appear on the map of Pallanteum/Rome.

Acarnania 5G

(Achaeans – Greeks)

Acrages 6B

Actium 5F

Aeneadae 3J

Aeolia 5C

Agathyrsians 1GHJ

Alba Longa 3B

(Albunea – fountain at Tibur)

(Alpheus – river in Elis)

(Amasenus – river in Latium)

(Amathus – town in Cyprus)

Amyclae 6G

Antandros 4K

(Appenninus – mountain in Italy)

Apulia 3D

Ara Maxima – Greatest Altar

(Araxes – river in Armenia)

Arcadia 5G

Ardea 3B

(Arethusa – fountain at Syracuse)

Argiletum

(Argives – Greeks)

Argos 5H

Arisba 4J

Arpi 3D

(Asian Marsh – on coast of Asia opposite Samos)

Asylum

(Athos – mountain in Macedonia)

(Atlas – mountain in Mauretania)

(Aufidus – river in Apulia)

Aulis 5H

(Auruncans – ancient people of central Italy)

(Ausonia – Italy)

Aventine Mount

(Avernus – lake near Cumae)

(Bactrians – people east of Caspian)

Baiae 4C

(Bebrycians – people south of Caspian)

Benacus 1A

(Berecyntus – mountain in Phrygia)

Boeotia 5H

Buthrotum 4F

Caere 3B

Caieta 3C

Camerina 6C

Campus Martius

Caphereus 5J

Capitol

Carinae

Carmental Gate

Carpathos 6K

Carthage 6A

Caspian Sea 2K

Caulonia 5D