The American Future (30 page)

Read The American Future Online

Authors: Simon Schama

A Cherokee family, photographed in the 1930s in North Carolina, in a rural setting much like that from which they had been expelled a century earlier.

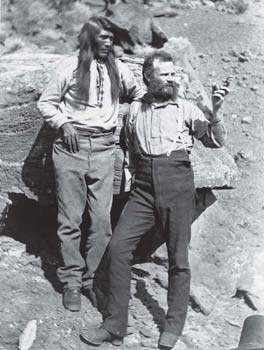

Major John Wesley Powell, one-armed explorer, geologist, and ecological prophet, with Tau-gu, chief of the Paiutes, Colorado Basin,1873.

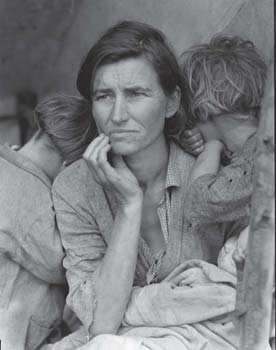

Dorothea Lange's great portrait of a migrant mother from the Dust Bowl, 1936.

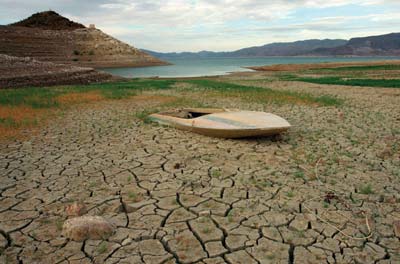

“Bath rings” and boat trapped in the dried bed of the drought-depleted Lake Mead reservoir, 2007.

The Klan's perversion of faith was extreme but it was a characteristic response to the experience of defeat and dispossession, clinging to a nostalgia for a form of Christian gentility that had only ever existed on the backs of slaves. Both black and white churches in the century after the Civil War were life rafts for people living in poverty and alienation. But while the black churches were constructive and forward-looking, emphasizing education and economic skills, planting in country and city the germs of self-determination, the white churches that ministered to the hard-up were most often defensive, fighting a furious rearguard action against the assembled forces of modernity: secularism, alcohol, Charles Darwin, and the latest satanic monster, showbiz. The answer to the last threat, of course, was to fight fire with fire, and launch what was in effect the Third Great Awakening: using the techniques of mass entertainment to steer the weak and sinful away from Babylon. It was a priceless gift that Billy Sunday, the battler against liquor, had been a professional baseball player (his name helped too). Movies of his revival sermons show Sunday using his slugger's swing to maximum effect when demon

strating what he would do with demon drink and those who profited from it.

White Pentecostalism, the Holiness movement, all made their deepest inroads, though, in the regions of the United States most vulnerable to economic distress: the prairies where corporate agriculture was uprooting the ancient American ideal of the family farm; the Great Plains where the dust storms blew away the hopes of the small farmer along with his topsoil; the Appalachians where coal miners were paid by “tickets” redeemable only through the company store, and were unprotected from the brutal emphysema and lesions that erupted in their bodies after years of toil at the coal face. Small mining towns like Pocahontas, West Virginia, where immigrant labor came from Hungary, Poland, and Ireland, became the theater of an all-out struggle between vice and salvation; the number of churches struggling to keep up with the saloons and whorehouses that competed for the miners' Sundays. The mining and railroad companies that wanted to protect their investment often funded the building of churches and the expenses of the minister. But the appeal of religion to all the Americans living hand to mouth in good times and disasters did not need the sanction of the bosses to make it compelling. Very oftenâwhether in big-city tenements or broken-down coal townsâit was the church that ministered to the sick; looked in when pantries were empty; made sure the kids were in school. And, to the dismay of management, the unorthodox fringe churches would often help out strikers when times got really rough. Near Birmingham, Alabama, the pastor of the Mount Hebron Baptist Church, where the congregation were mill workers and small tenant farmers, was Fred Maxey, who made no apology for showing up at union rallies, going out of his way to minister to black and white alike. Needless to say a Klan cross was burned outside his church.

The twentieth-century church of the white poor, then, was not monopolized by reaction. There had been, in fact, a change in party identification. The great Christian revival orator and Democrat populist William Jennings Bryan had mobilized a huge rural constituency behind his attacks on the bastions of capitalism: Wall Street, the banks that, in the name of the gold standard, made credit tough for the little man. Conversely, after Theodore Roosevelt left the White House,

the Republicans cozied up to business. By the time the roof fell in on American capitalism in 1929, the natural alliance between Irish Democrats and the Catholic Church had been augmented by another between white rural Protestants in the South and Midwest. In the harder-hit areas of the industrial South, joining an evangelical revival church was a way to cut loose from management-endorsed Sunday worship and establish an independent sense of community. One disgruntled textile mill owner complained that holy rollers “tear up a village, keep folks at meetings till all hours at night so they are not to fit to work the next morning.”

A remarkable Alabama woman, Myrtle Lawrence, illiterate white sharecropper, stalwart of the Taylor Springs Baptist Church and the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union, came to New York in 1937 for National Sharecroppers' Week, organized by New Deal government agencies. What the united ranks of union organizers and government progressives would have liked, as the historian Wayne Flynt observes, was someone beauteous in poverty, straight out of a Dorothea Lange photograph. What they got instead was toothless Myrtle Lawrence, snorting snuff, chewing quids, and hurtling gobs of juice into her pink-wrapped spit box before plunging into prayers and hymns with raw Old Time gusto. But on one principle, Myrtle could not be faulted by the high-minded New Dealers: she thought blacks fellow Americans, welcomed in the love of Jesus. At the YWCA Summer School in North Carolina, she told an English class, “They eat the same kind of food we eat; they live in the same kind of shacks that we live in; they work for the same boss men that we work for; they hoe beside us in the fields; they drink out of the same bucket that we drink out of; ignorance is killing them just the same as it's killing us. Why shouldn't they belong to the same union that we belong to?” Myrtle and Fannie Lou would surely have got along.

Ruleville, Mississippi, 31 August 1962

She knew why she had to get on that bus, and it wasn't because no out-of-state kids who'd come to Mississippi had told her to. No, sir, it was what she'd heard in the little chapel in Ruleville from Reverend Story that Sunday; God speaking directly to her, though the words came out of the mouths of all those young men with their fine hopes. Fannie

Lou was sick and tired of being sick and tired. She had had enough of breaking her back every day in the fields so she could put bread on the table; enough of being frightened she might be put out of her house if she so much as went near the folks organizing in Greenwood for the vote; talking about sitting in on lunch counters; in the front of the bus. Wasn't it enough that she couldn't have children of her own; that they had taken her and done something to her that made sure of that without so much as asking her first? And now what was she supposed to do with all that welling up of feeling; knowing that it was more than high time that promises made should be promises kept; that she and people like her could have the decencies of life, starting with the vote? And if she got scared at the thought of what she was going to do, she just did what she couldn't but help: she sang. She would lean over the cot and sing to her little Vergie. “This little light of mine, I'm gonna let it shine,” she would sing, and her adopted girl would smile and sleep.

They were going to Indianola, twenty-six miles down the road, the road that went straight through the cotton fields past W. D. Marlowe's plantation where she sweated for her share or kept time for the croppers. In Indianola, Mr. Charles McLaurin had said, they would all register to vote as was their born right and something would get started in the Delta. The yellow bus rolled up by the water tower, and on they all got, mostly the folks of the church and a few of the organizers to see everything went as it should. But there was a pit in their stomachs and they sat there, low and quiet like the children who would usually be in the seats. The drive seemed endless. Every time a pickup went past, they could see pink and red faces looking hard at the bus, some of them scowling, the trucks making a swerve to bother them. Those twenty-six miles seemed the longest ride of their lives.

When they got to the city offices by the bayou, out they climbed. Word must surely have got out as there was a whole bunch of state troopers and highway patrolmen there, looking at them hard as if they were taking photographs. And they made it plain to McLaurin that there would be just two of them let in for the registration that day and if they didn't care for that, well, that was just too bad. Now Fannie Lou had worked her hardest at preparing herself for all the complicated questions she knew would be put in her way like a briar

patch, but they had sure done a good job in making it hard and she was beat if she knew when this and that clause of the constitution of the state of Mississippi had become law and others had not. There was a good deal of head and pencil scratching; hours of it, the August sweat made worse by her nerves, before she handed in the papers to the hard-eyed white man at his desk. Ushered outside to wait, she already knew she wasn't going to be given what she had come for, not that day anywise, so it was no surprise when Fannie Lou was told she had failed the test the state needed to verify her credentials as a voter. One day soon Fannie Lou knew it would be different, so when they climbed aboard the bus she could not take it as defeat.

The bus pulled out of Indianola, but as the evening closed in, so did the bad feeling. They all sat there in the bus as quietly as they had come; but then the traffic outside on the road picked up, and much of it was men in trucks who had taken the shotguns off their racks and were waving them in the air at the bus, hollerin, “Fuck you niggers, we'll

kill

you niggers before you EVER get the vote.” And then came the police cars flashing their lights and cutting them off, and the officer got the driver out and told him he had no right taking passengers seeing as the bus was too yellow; that it was “impersonating a school bus.” There was a fine to be paid; and there was a go-round the bus for the money and it got handed over, but still they took the driver away.

So how were they to get back home now? No one on the bus had ever driven anything, that's for sure. So there they sat, in the thick Delta night, a stew of fright and despair. Even McLaurin seemed to have lost his voice. No one knew what to do; what might become of them. They could feel their own sweat go cold. But then, from somewhere in the back of the bus, a sound started; a voice, pure and low, just easing out into the air; Fannie Lou's voice.

“This little light of mine,” it sang,

I'm gonna let it shine

This little light of mine

I'm gonna let it shine

And the voices joined in. They were sovereign; invincible. They had the Lord with them. They would overcome.

The evening was winding down. The British-and-damned-proud-of-it grub (minty pea soup, salmon, roast beef, berries) had been polished off. The last of the daylight was fading through the sash windows. Some fifty or so guests, faces shiny with satisfaction and wine, were pushing chairs back and slowly making their way into the adjoining room for coffee and a dram, though neither the prime minister nor the president would touch a drop. We were a mixed bunch: cabinet ministers in varying states of merriment or beleaguered solemnity; the World's Most Important Media Tycoon (saturnine, imperiously unfriendly); and an unlikely prattle of historians. Invitations had gone out indicating passionate interest in the subject on the part of both chief executives. This is certainly true of the prime minister, who has a PhD in history, but it was a stretch to imagine George Bush with a heavily thumbed edition of Gibbon on the bedside table, even though a chronicle of the fate awaiting overextended empires might not go amiss.

Some of the tribe of Clio were loyal enthusiasts of the president, whose popularity ratings at home were sinking even faster than the Dow Jones. Others among us had reconciled our uneasy consciences by telling ourselves that if we were in the history business, how could we possibly stay away? But what sort of business was that? In what, precisely, were we being implicated? The general idea of the evening seemed to be that if a gathering of historians was convened in sufficient density, the moment itself would, by some act of cultural osmosis, become Historic. We who had communed in our pages with Churchill and de Gaulle, would now sprinkle a little Significance around like air freshener in the parlor of exhausted power.

Into the drawing roomâa Quinlan Terry extravaganza in terra-cotta,

edged with gilt reliefs, the result of a decorating epiphany experienced by Mrs. Thatcher in Nancy Reagan's White Houseâstrode the hurting titans. During the early stages of the dinner, Bush seemed oddly ill at ease, especially for someone getting a respite from the gloomy sibyls at home. A generously fraternal speech by Gordon Brown, lauding the bond between the two democracies and ending in a toast, was met with an aw-shucks response as POTUS got to his feet, evidently underbriefed about this particular moment in the proceedings. “Guess I'd better say something,” he thought out loud before offering the communiqué that “relations between the United States and the United Kingdom are goodâ¦[long pause] in fact,

damned

good.” And that was pretty much it for hands across the sea. He seemed oddly diminished, someone who, for reasons he couldn't quite fathom, had discovered the armchair he'd been sitting in for years was now too big and his legs no longer touched the floor; the incredible shrinking prez. Over the pea soup, the shoulder-slapping bonhomie withered to a dry little tic of humorous coughs, eyebrows suspended between hilarity and uncertainty, like a stand-up comic sweating through a tough house on a Monday night in Milwaukee.

For a minute or two after the photo op, George Bush was left to his own devices and came my way. (Improbable, but true.) He looked unmistakably like a man in need of a drink; but since he had sworn off ever having one, and since I had a glass of cognac in my hand, the least I could do was say a word that would get him through the rest of the evening, and that word was: “Texas.” The pick-me-up worked an instant transformation: the officially synthetic grin replaced by the real thing. Our television crew was off there soon, I explained, to make a film about immigration history. Then I reeled off a string of place names that were country music to his ears: “El Paso,” “Brownsville,” “Laredo.” Some of the earlier discomfort, I realized, was that of a man who traveled abroad only so that he could feel a little pop of joy when he got within honking distance of the Houston freeways. “Your policy on immigration,” I said, the cognac making me cheeky, “is about the only policy I've agreed with; and that's because it put you way to the left of your party.” It was true, if patronizing. The line in the Republican Party over what to do about the twelve million illegal immigrants in the United States, the overwhelming majority Hispanic, runs between those for whom fencing, discovery, and deportation are the beginning

and end of policy, and those like Bush and McCain, who have long been in the world of the Hispanic Southwest, and want to find some way to get the illegals to citizenship. Even the lamest of lame-duck presidents didn't need a pat on the head from someone who was not going to be lining up anytime soon for the job of ghosting the memoirs. But Bush took the condescension in good part because, I suspect, his head was off somewhere far away from Whitehall, mooching around the chaparral, where the lights of Houston oil refineries were still benevolent twinkles on the unlimited horizon of Texan plenty.

Bringing him back from the sagebrush, I asked, “So why do you suppose immigration turned out not to be the hot-button issue for your party?” I mentioned the standard-bearer of anti-illegal hard-line enforcement among the candidates, the Colorado congressman Tom Tancredo, who, despite the ranting of hard-core radio demagogues prophesying the End of America, had gone nowhere in the primaries. “Tancredo,” said Bush, incredulously, rolling his eyes and lightly snorting like one of his own horses, adding under his breath, “is an idiot.” He then complained a bit how he could have got a benign immigration reform bill enacted, guaranteeing medical and social services to at least the children of illegals, had it not been for the Machiavellian obstructionism of the Democratic Senate Majority leader Harry Reid. Then he made a suggestion for our film shoot. “I knew the border real well, back when it was just about the worst, dirt-poor place in America; I could tell you stories of those days in the fifties; of how people who'd jumped the line survived, what they worked for day and night.” He paused, brows knitted again, and then suggested we take a look at old stills of the way Brownsville and the pueblos the other side of the border were half a century agoâshacks and ratsâand compare them to the way those towns are now; which is, for all the trouble and grief, materially better. There had been, he reminded me, a huge shift within Mexico itself; people from the country moving steadily, unstoppably north, to the world of the Norteamericanos.

Back in the States at that very moment, two sure things were going down. Someone at a gas station was jacking up the price to as close to five dollars a gallon as they could get it, and along the Rio Grande, and in the unforgiving desert,

coyotes

(people smugglers) were trying to get a hundred souls

every hour

to make that crossing. Homes were being repossessed every time you looked; banks were hitting the deck,

taking the bankers with them. Suddenly there might be a lot fewer center-hall colonial McMansions to clean, or prairie-size lawns to cut. The job lines would rise, skyrocketing oil prices would hike transportation costs, and the cost of food would head north too. Though one had nothing to do with the other, the pressure on jobs would spur hard-core right-wing radio ravers, like the comically self-named Michael Savage, to yet more foaming waves of abuse. The immigrants were parasitic vermin, barely human, battening on the wasted flesh of the body politic, sucking taxes from law-abiding citizens, taking jobs away from lunch-pail Joe.

But none of this matters to the unstoppable stream. On it comes. Twelve million undocumented and around a million more each year for the foreseeable future; right now the biggest human migration on the face of the planet. And they come not just from Mexico and Central America; but to New York from Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, from Cambodia and Liberia and Senegal. If they could only get out of the prison their government has made for them, the entire population of Myanmar would fetch up in New York Harbor tomorrow. And why? Because of two dramatic utterances. The first was Tom Paine's pronouncement in

Common Sense

(1776) that the “New World has been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty.” But that was to define America as the abode of free conscience and would have been a little lofty for those just wanting to climb out of a Pomeranian mud hole, let alone a corrugated-roof shack in Guatemala City, into something approximating a human existence. For them, another work was written, by a native-born Frenchman on his farm in Orange County, New York. The book, which seemed like a memoir but was at least as much romance, was called

Letters from an American Farmer

(1782), and it was the first great work of American literature. Chapter Two of

Letters

is titled “What is an American?” A whole century before the Sephardi Jewish poet Emma Lazarus declaimed in words graven into the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty that America would be decent enough to receive the “wretched refuse of the teeming shore,” J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur had already lit the candle of hope that would reach across oceans and continents to millions. The emblems of American self-sufficiency, the log cabin and the homestead farm, were already declared by Crèvecoeur to be the social cells of democracy.

And they were within the reach of anyone who had the gump

tion to choose to live a free life in an open country. In Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, the servile peasant and the human effluent of the cities would be reborn as John Citizen. (Jane was not discussed.) Released from having to defer to aristocrats and ecclesiastics, common humanity would be liberated to realize its true, boundless potential. Happiness was on the horizon. “We have no princes for whom we toil or bleed,” wrote Crèvecoeur. “We are the most perfect society now existing in the world. Here man is free as it ought to be.” Now why, then, should a man remain in the social prisons of European tradition? Why would anyone with a grain of common sense or self-respect feel attachment to the accidental geography of his nativity, for “a country that had no bread for him, whose fields procured him no harvest, who met with nothing but the frowns of the rich, the severity of the laws, with jails, punishments, who owned not a single foot of the extensive surface of the planet?” To leave such vexation behind was to experience social rebirth. What is an American, then? “He is an American, who leaving behind him, all his ancient prejudices and manners, receives new ones from the new mode of life he has embraced, the government he obeys and the new rank he holds. He becomes an American by being received into the broad lap of Alma Mater. Here individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men, whose labours and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world.” Let such melting commence! And the misery-stricken of the world would no longer be the defenseless creatures of the mighty. In America they would be something else: self-made men; citizens.