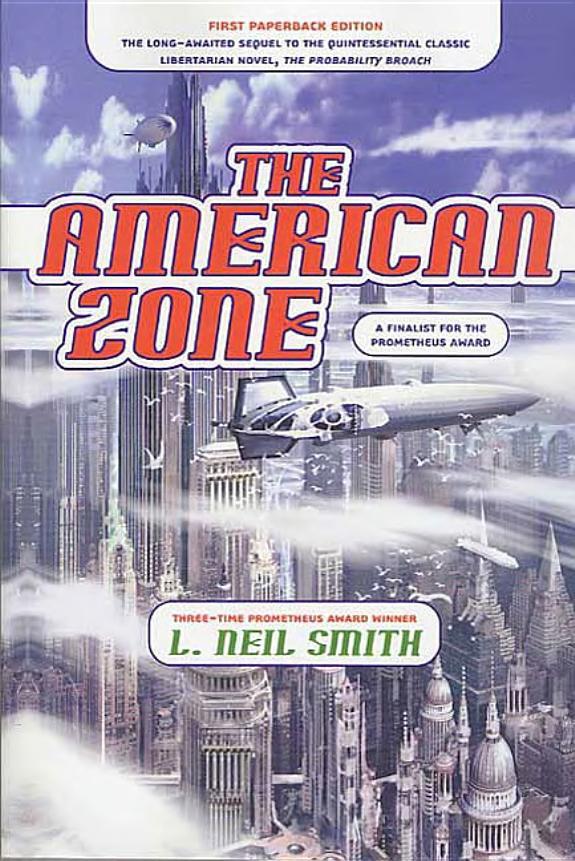

The American Zone

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

FOR KEN FLURCHICK

(and all of you others who wanted another

straightforward, no nonsense novel about Win Bear in the

North American Confederacy).

straightforward, no nonsense novel about Win Bear in the

North American Confederacy).

Hey, Kenny, we’re goin’ home!

THERE’S AN AWFUL LOT in this book that I owe to the late, great Robert LeFevre. I’d also like to acknowledge the groundbreaking brainwork of David F. Nolan, founder of the Libertarian Party, and Marshall Fritz, founder of Advocates for Self-Government and the Separation of School and State Foundation, in devising the political diamond Lucy describes in Chapter 17. My conclusion with regard to what lurks at the bottom corner of the diamond differs from theirs.

MANY THANKS to European American Armory of Cocoa, Florida, to Crimson Trace Corporation of Beaverton, Oregon, and to Chris Reeve Knives of Boise, Idaho, for their valuable assistance in making this a more interesting book than it might otherwise have been.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Notice

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

1: A YANKEE DOODLE DANDY

2: SMOKE GETS IN YOUR EYES

3: JOSHUR FIT DE BATTLE

4: TABERNA EST IN OPPIDUM

5: EASY WINNERS

6: HELL IN A BUCKET

7: LAWYERS, GUNS, AND MONEY

8: ALONG GAME THE F.F.V

9: CUTS LIKE A KNIFE

10: BEAUTIFUL, BEAUTIFUL TEXAS

11: I NEED A HERO

12: LAY THAT PISTOL DOWN

13: THE JAVA JIVE

14: THREE DOLLAR BILL

15: BACK HOME AGAIN

16: TAKE ME OUT TO THE BALL GAME

17: STUCK IN THE MIDDLE WITH YOU

18: THANK GOD AND GREYHOUND YOU’RE GONE

19: IT’S SISTER JENNIE’S TURN TO THROW THE BOMB

20: THAT’S ENTERTAINMENT

21: TEA FOR TWO

22: ROLL ME OVER IN THE CLOVER

23: MONEY FOR NOTHING

24 THERE’LL NEVER BE ANOTHER YOU

25: POISONING PIGEONS IN THE PARK

26: STRANGER IN PARADISE

27: RATTLESNAKE MOUNTAIN

28: TEN LITTLE INDIANS

29: MY BLUE HEAVEN

30: DIRTY LAUNDRY

BOOKS BY L. NEIL SMITH

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Copyright Page

Copyright Notice

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

1: A YANKEE DOODLE DANDY

2: SMOKE GETS IN YOUR EYES

3: JOSHUR FIT DE BATTLE

4: TABERNA EST IN OPPIDUM

5: EASY WINNERS

6: HELL IN A BUCKET

7: LAWYERS, GUNS, AND MONEY

8: ALONG GAME THE F.F.V

9: CUTS LIKE A KNIFE

10: BEAUTIFUL, BEAUTIFUL TEXAS

11: I NEED A HERO

12: LAY THAT PISTOL DOWN

13: THE JAVA JIVE

14: THREE DOLLAR BILL

15: BACK HOME AGAIN

16: TAKE ME OUT TO THE BALL GAME

17: STUCK IN THE MIDDLE WITH YOU

18: THANK GOD AND GREYHOUND YOU’RE GONE

19: IT’S SISTER JENNIE’S TURN TO THROW THE BOMB

20: THAT’S ENTERTAINMENT

21: TEA FOR TWO

22: ROLL ME OVER IN THE CLOVER

23: MONEY FOR NOTHING

24 THERE’LL NEVER BE ANOTHER YOU

25: POISONING PIGEONS IN THE PARK

26: STRANGER IN PARADISE

27: RATTLESNAKE MOUNTAIN

28: TEN LITTLE INDIANS

29: MY BLUE HEAVEN

30: DIRTY LAUNDRY

BOOKS BY L. NEIL SMITH

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Copyright Page

The great secret of life lies in choosing the right woman. It’s a

mother’s

job to tell you not to play with fire. Marry the girl who tells you, “Go ahead.”

mother’s

job to tell you not to play with fire. Marry the girl who tells you, “Go ahead.”

—Memoirs of Lucille G. Kropotkin,

Whoooooosh

…

Bang!

…

Bang!

The pop-bottle rocket, fired past me from across the street, damn near singed my eyebrows.

Offering some unseen neighbor the middle-finger salute, I backed off the balcony, through the sliding transparent doors, and into the relative security of my living room. Even if things got out of hand and something made it through the doors, the glass would heal itself by morning—which was more than could be said for me.

Sometime tomorrow I’d remind myself to have a word with an overly zealous patriot.

On second thought, he (or she) could hardly be blamed for his (or her) enthusiasm. I’d probably just remind myself to skip the whole thing. Nearly having my beezer Francis-Scott-Keyed off was certainly no more than I deserved for having foolishly poked it outdoors on this night of nights.

After all, it was July Second, 220 A.L., and across the vast, twilit metropolis that was Greater LaPorte, sprawled from the Cache la Poudre River to Pistol Sight Mountain between the toes of the Rocky Mountain foothills (in a region many another culture labels “northern Colorado”), hundreds of city neighborhoods had already begun twinkling, sparkling, and sputtering, snapping, crackling, and

popping!

in blissful commemoration of the signing of a certain illegal document that had made young

Tommy Jefferson and his little playmates terrorists in the eyes of the British Crown.

popping!

in blissful commemoration of the signing of a certain illegal document that had made young

Tommy Jefferson and his little playmates terrorists in the eyes of the British Crown.

Yes indeed, it was high summer once again on the High Plains, and—perhaps just a little high themselves by now—the good ladies and gentlemen of the North American Confederacy were celebrating their favorite occasion: Independence Day. Here in the Confederacy, it actually still meant something. And it probably helped that there wasn’t a building in all of Greater LaPorte that would burn any longer than thirty seconds, even if you dropped napalm on it.

For the first time in a long while, I glanced down at my left hand where I had a place-keeping finger stuck between the pages of a freshly imported hardcover I’d just brought home that afternoon:

Al Franker Is a Pathetic Little Wannabe

by Rush H. Limbaugh. I hadn’t gotten past the introduction so far. Turning my back to the colorful display outside, crossing a living room carpet the size of a small basketball court to the wet bar, I poured myself a scotch and scotch, adding a dash of scotch for flavor.

Al Franker Is a Pathetic Little Wannabe

by Rush H. Limbaugh. I hadn’t gotten past the introduction so far. Turning my back to the colorful display outside, crossing a living room carpet the size of a small basketball court to the wet bar, I poured myself a scotch and scotch, adding a dash of scotch for flavor.

It smelled wonderful. I’d tried Irish whiskey once, Bushmill’s. It smells even better, but it tastes too damned good, and for someone who has a little trouble in that direction already, it’s a gold-plated invitation to alcoholism.

The fact is, I’d have enjoyed celebrating, too, especially here, in the heart of one of the Confederacy’s great cities. But my heart’s companion (and the most luscious female I’ve ever met), Healer Clarissa MacDougall Olson-Bear, was busy making house-calls—as she always was on July Second—attending to such seasonal calamities as scorched fingers, ruptured eardrums, and dittoed eyeballs. For what is there worthwhile in life that

doesn’t

involve some hazard?

doesn’t

involve some hazard?

Back where I came from originally, such a ruggedly Darwinistic sentiment would likely have soiled the lace unmentionables

of the whole Volvo-driving, wine-and-cheese gobbling, no-sparrow-shall-hiccup set of what the author I was reading called “lifestyle Nazis.” But I ask you, what’s left of the meaning of Independence Day, if you let some jumped-up city council, some upstart county commission, or some state legislature that doesn’t know its place, confiscate your Roman candles, your M-80s, or your pop-bottle rockets? North American Confederates would laugh out loud at such a contradiction—once the gunsmoke had cleared and the politicians’ bleeding carcasses had been hauled away.

of the whole Volvo-driving, wine-and-cheese gobbling, no-sparrow-shall-hiccup set of what the author I was reading called “lifestyle Nazis.” But I ask you, what’s left of the meaning of Independence Day, if you let some jumped-up city council, some upstart county commission, or some state legislature that doesn’t know its place, confiscate your Roman candles, your M-80s, or your pop-bottle rockets? North American Confederates would laugh out loud at such a contradiction—once the gunsmoke had cleared and the politicians’ bleeding carcasses had been hauled away.

Leaving the book facedown on the bar, I found a comfy chair to sit in near the big glass doors and started to offer a lonely toast to my sad reflection. But just as you’re really beginning to enjoy feeling sorry for yourself, there’s always somebody who comes along and spoils it for you. This time it was my wife’s cat Silvertip—now where had she come from?—who hopped up into my lap and settled down, purring like a contented meatloaf. I say my wife’s cat. From the moment Clarissa had brought the little gray and white feline home, she’d decided she was mine—or rather, I was hers. Okay, then, happy July Second, kittycat. And happy July Second, private detective Edward William “Win” Bear. What the hell. Clarissa would be back sometime during the wee, small hours, and she’d be here tomorrow, and the day after that, and the day after that … What more can a middle-aged fat man ask for?

Silvertip wasn’t any help; she looked up at me and asked, “Eww?”

As if in answer to my unasked question, the doorbell chose that moment to ring. Silvertip jumped off my lap, leaving poke-marks in my trousers—not to mention the flesh inside them—and headed upstairs. She doesn’t really like anybody but Clarissa and me.

Grudgingly, I rose to answer the door, not even bothering to glance at the monitor on my way over to the half-flight of steps that led down to the front door. I’d seriously considered not answering it at all, but only for a moment. My guess was that I was about to have some Independence Day customers, myself.

Understand that it had taken me

years

to acquire any kind of professional reputation in the virtually crime-free Confederacy, where Captain Sam Colt had made everybody equal and President Albert Gallatin had kept’em that way (not necessarily in that order). People tend to mind their own business as a consequence, and have very little use for detectives, private or otherwise. If I wanted to hold on to that living room that you could land small aircraft in, and all the rest of 626 Genet Place that went with it (not to mention my own self-respect in a culture where absolutely nobody rushes to protect you from feeling ashamed of being a bum), I couldn’t afford to lose any live ones—even if it meant going to work on the Glorious Second.

years

to acquire any kind of professional reputation in the virtually crime-free Confederacy, where Captain Sam Colt had made everybody equal and President Albert Gallatin had kept’em that way (not necessarily in that order). People tend to mind their own business as a consequence, and have very little use for detectives, private or otherwise. If I wanted to hold on to that living room that you could land small aircraft in, and all the rest of 626 Genet Place that went with it (not to mention my own self-respect in a culture where absolutely nobody rushes to protect you from feeling ashamed of being a bum), I couldn’t afford to lose any live ones—even if it meant going to work on the Glorious Second.

I did make sure that my trusty old .41 Magnum Model 58 Military & Police revolver was still hanging where it was supposed to be, from beneath my left armpit, underneath my tunic. I’d made one or two—hundred—folks a bit unhappy with me over the nine years since I’d come to the Confederacy. Now was not the time—with my personal physician out of the house—to get careless.

The front hall monitor was considerably less easy to ignore than its upstairs equivalent; it took up the whole front door. Turned out there were two of them, standing out there in the fireworks-light; I could see them (with the technology behind that monitor I could have seen them if it’d been a pitch-black overcast night and Mount Colfax was filling the air with volcanic ash) but they couldn’t see me. Which may be the reason I gasped and stumbled on the last step, fetching up against the wall of the

stairwell and damn near spilling the drink I’d forgotten I was holding.

stairwell and damn near spilling the drink I’d forgotten I was holding.

Mindful of making a good first impression on new clients, I opened the coat closet at the bottom of the stairs, stuck the drink on the top shelf between a couple of hats, shut the closet door with one hand, summoned up my Grade-Two Professional Smile, and opened the front door with the other.

The monitor hadn’t lied.

The couple apparently seeking my services this holiday evening had seemed familiar from the first moment I’d seen their images at the top of the stairs. No less so now. He was perpetually fiftyish-looking and of medium height, with a uniquely textured voice, broad shoulders, compelling eyes, a bristly salt-and-pepper mustache, and rather conspicuous ears. Several strands of his hair fell sort of boyishly across his forehead and into his eyes.

She was a thin, not-quite-pretty, fortyish platinum blond (“Better living through chemistry,” I quoted to myself before I could stop me) with nervous mannerisms and what I was soon to discover was an exceptionally sharp tongue.

Together they informed me they’d been referred by an old mutual friend, one Lucille Gallegos Kropotkin—a former neighbor of mine who was presently out exploring the Asteroid Belt—and introduced themselves as Carole and Clark.

As in Carole Lombard.

And Clark Gable.

Whah, Ah do beeleeve, ef Ah’d been Scarlett O’Hara, Ah would hev jist

swooned

.

swooned

.

You-all, honeychile.

Other books

Murder at the Opera by Margaret Truman

WWW 3: Wonder by Robert J Sawyer

Stone Cold Crazy (Lil & Boris #4) (Lil and Boris Mysteries) by Shannon Hill

The Secret Love of a Gentleman by Jane Lark

Destination Wedding by Rebecca York

The City of Ember by Jeanne DuPrau

The New Eve by Robert Lewis

Eternal Envy (The Seven Sin Sisters 2) by Beck, Paloma

Forbidden Planets by Peter Crowther (Ed)

The Quiche of Death by M. C. Beaton