The Anatomy of Story (45 page)

Read The Anatomy of Story Online

Authors: John Truby

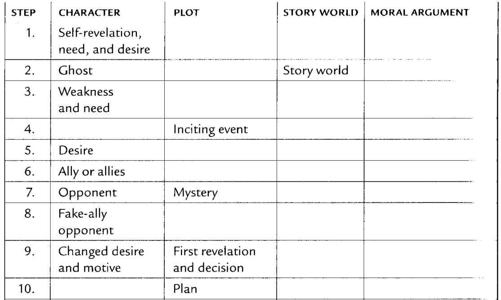

The following description of the twenty-two steps will show you how to use them to figure out your plot. After I explain a step, I will show you an example of that step from two films,

Casablanca

and

Tootsie.

These films represent two different genres—love story and comedy—and were written forty years apart. Yet both hit the twenty-two steps as they build their organic plots steadily from beginning to end.

Always remember that these steps are a powerful tool for writing but are not carved in stone. So be flexible when applying them. Every good story works through the steps in a slightly different order. You must find the order that works best for your unique plot and characters.

1. Self-Revelation, Need, and Desire

Self revelation, need, and desire represent the overall range of change of your hero in the story. A combination of Steps 20, 3, and 5, this frame gives yon the structural "journey" your hero will take. You'll recall that in Chapter 4, on character, we started at the endpoint of your hero's development by figuring out his self-revelation. Then we returned to the beginning to get his weakness and need and his desire. We must use the same process when determining the plot.

By starting with the frame of the story—self-revelation to weakness, need, and desire—we establish the endpoint of the plot first. Then every step we take will lead us directly where we want to go.

When looking at the framing step of the plot, ask yourself these ques-tions, and be very specific in your answers:

■ What will my hero learn at the end?

■ What does he know at the beginning? No character is a completely

blank slate at the start of the story. He believes certain things. ■ What is he

wrong

about at the beginning? Your hero cannot learn something at the end of the story unless he is wrong about something at the beginning.

Casablanca

■ Self-Revelation

Rick realizes he cannot withdraw from the fight for freedom simply because he was hurt by love.

■ Psychological Need

To overcome his bitterness toward Ilsa, regain a reason for living, and renew his faith in his ideals. ■

Moral Need

To stop looking out for himself at the expense of others. ■

Desire

To get Ilsa back.

■ Initial Error

Rick thinks of himself as a dead man, just marking time. The affairs of the world are not his concern.

Tootsie

■ Self-Revelation

Michael realizes he has treated women as sex objects and, because of that, he has been less of a man.

■ Psychological

Need To overcome his arrogance toward women and learn to honestly give and receive love.

■ Moral Need

To stop lying and using women to get what he wants.

■ Desire

He wants Julie, an actress on the show.

■ Initial Error

Michael thinks he is a decent person in dealing with women and that it is OK to lie to them.

2. Ghost and Story World

Step 1 sets the frame of your story. From Step 2 on, we will work through the structure steps in the order that they occur in a typical story. Keep in mind, however, that the number and sequence of steps may differ, depending on the unique story you wish to tell.

Ghost

You are probably familiar with the term "backstory." Backstory is everything that has happened to the hero before the story you are telling begins. I rarely use the term "backstory" because it is too broad to be useful. The audience is not interested in everything that has happened to the hero. They are interested in the essentials. That's why the term "ghost" is much better.

There are two kinds of ghosts in a story. The first and most common is an event from the past that still haunts the hero in the present. The ghost is an open wound that is often the source of the hero's psychological and moral weakness. The ghost is also a device that lets you extend the hero's organic development backward, before the start of your story. So the ghost is a major part of the story's foundation.

You can also think of this first kind of ghost as the hero's

internal opponent.

It is the great fear that is holding him back from action. Structurally, the ghost acts as a counterdesire. The hero's desire drives him forward; his ghost holds him back. Henrik Ibsen, whose plays put great emphasis on the ghost, described this structure step as "sailing with a corpse in the cargo."

5

Hamlet

(by William Shakespeare, circa 1601)

Shakespeare was a writer who knew the value of a ghost. Before page 1, Hamlet's uncle has murdered his father, the king, and then married

Hamlet's mother. As if that wasn't enough ghost, Shakespeare introduces in the first few pages the actual ghost of the dead king, who demands that Hamlet take his revenge. Hamlet says, "The time is out of joint: O cursed spite, / That ever I was born to set it right!"

It's a Wonderful Life

(short story "The Greatest Gift" by Philip Van Doren Stern, screenplay by

Frances Goodrich & Albert Hackett and Frank Capra, 1946)

George Bailey's desire is to see the world and build things. But his ghost his fear of what the tyrant Potter will do to his friends and family if he leaves—holds him back.

A second kind of ghost, though uncommon, is a story in which a ghost is not possible because the hero lives in a paradise world. Instead of starting the story in slavery—in part because of his ghost—the hero begins free. But an attack will soon change all that.

Meet Me in St. Louis

and

The Deer Hunter

are examples.

A word of caution is warranted here. Don't overwrite exposition at the start of your story. Many writers try to tell the audience everything about their hero from the first page, including the how and why of the ghost. This mass of information actually pushes your audience away from your story. Instead, try

withholding

a lot of information about your hero, including the details of his ghost. The audience will guess that you are hiding something and will literally come toward your story. They think, "There's something going on here, and I'm going to figure out what it is."

Occasionally, the ghost event occurs in the first few scenes. But it's much more common for another character to explain the hero's ghost somewhere in the first third of the story. (In rare instances, the ghost is exposed in the self-revelation near the end of the story. But this is usually a bad idea, because then the ghost—the power of the past—dominates the story and keeps pulling everything backward.)

Story World

Like the ghost, the story world is present from the very beginning of the story. It is where your hero lives. Comprised of the arena, natural settings, weather, man-made spaces, technology, and time, the world is one of the

main ways you define your hero and the other characters. These characters and their values in turn define the world (see Chapter 6, "Story World," for details).

KEY POINT: The story world should be an expression of your hero. It shows your hero's weaknesses, needs, desires, and obstacles.

KEY POINT: If your hero begins the story enslaved in some way, the story world will also be enslaving and should highlight or exacerbate your hero's great weakness.

You place your hero within a story world from page 1. But many of the twenty-two steps will have a unique subworld of their own.

Note that conventional wisdom in screenwriting holds that unless you are writing fantasy or science fiction, you should sketch the world of your story quickly so that you can get to the hero's desire line. Nothing could be further from the truth. No matter what kind of story you are writing, you must create a unique and detailed world. Audiences love to find themselves in a special story world. If you provide a story world, viewers won't want to leave, and they will return to it again and again.

Casablanca

■ Ghost

Rick fought against the Fascists in Spain and ran guns to the Ethiopians fighting the Italians. His reason for leaving America is a mystery. Rick is haunted by the memory of Ilsa deserting him in Paris.

■ Story World

Casablanca

spends a great deal of time at the beginning detailing a very complex story world. Using voice-over and a map (a miniature), a narrator shows masses of refugees streaming out of Nazi-occupied Europe to the distant desert outpost of Casablanca in North Africa. Instead of getting quickly to what the main character wants, the film shows a number of refugees all seeking visas to leave Casablanca for the freedom of Portugal and America. This is a community of world citizens, all trapped like animals in a pen.

The writers continue to detail the story world with a scene of the Nazi Major Strasser being met at the airport by the French chief of police, Captain Renault. Casablanca is a confusing mix of political

power, a limbo world: Vichy French are allegedly

in

charge, but real power rests with the Nazi occupiers.

Within the story arena of Casablanca, Rick has carved out a little island of power in his grand bar and casino, Rick's Cafe Americain. He is depicted as the king in his court. All the minor characters play clearly defined roles in this world. Indeed, part of the pleasure the audience takes from the film is seeing how comfortable all the characters are in the hierarchy. Ironically, this film about freedom fighters is, in that sense, very antidemocratic.

The bar is also a venal place, a perfect representation of Rick's cynicism and selfishness.

Tootsie

■ Ghost There is no specific event in Michael's past that is haunting him now. But he has a history of being impossible to deal with, which is why he can no longer get work as an actor.

■ Story World From the opening credits, Michael is immersed in the world of acting and the entertainment business in New York. This is a world that values looks, fame, and money. The system is extremely hierarchical, with a few star actors at the top who get all the jobs and a mass of struggling unknowns at the bottom who can't find roles and must wait on tables to pay the rent. Michael's life consists of teaching the craft of acting, going on endless auditions, and fighting with directors over how to play a part.

Once Michael disguised as Dorothy wins a part on a soap opera, the story shifts to the world of daytime television. This is theater totally dominated by commerce, so actors perform silly, melodramatic scenes at top speed and move quickly to the next setup. This is also a very chauvinistic world, dominated by an arrogant male director who patronizes every woman on the set.

The man-made spaces of Michael's world are the tiny apartments of the struggling actors and the television studio in which the show is shot. The studio is a place of make-believe and role-playing, perfect for a man who is trying to pass as a woman. The tools of this world are the tools of the acting trade: voice, body, hair, makeup, and costume. The writers create a nice parallel between the makeup