The Arithmetic of Life and Death (10 page)

Read The Arithmetic of Life and Death Online

Authors: George Shaffner

Tags: #Philosophy, #Movements, #Phenomenology, #Pragmatism, #Logic

At that moment, there were twelve guests in the Mayfly, which was only 80 percent of opening day capacity. It had been open for thirty minutes, which was just 2.5 minutes per guest and less than 30 percent of the carefully modeled eight minutes forecast. Yet, the restaurateur’s single-server model had completely broken down. In a panic, he retreated to the kitchen to try to figure out what to do. Just as he was beginning to revise his service model to accommodate the chaotic arrival of multiple, mutually exclusive requests, a busload of tourists from the south side of Chicago squeezed into the front of the restaurant.

At that moment, Joe Bob, the couple, and the family of five got up and left, never to return. No one knows what happened to the proprietor, who seemed to vanish into thin air, but the rumor around Alki is that the four stevedores worked together to make the tourists a superb spaghetti Bolognese, and a good time was had by all in the Mayfly’s final hour.

Whether it’s restaurants or 777s or anything else, it’s an interdependent world. Teams rule. There is no such thing as a sole proprietor—everyone relies on many suppliers. Even hermits depend on others to provide electricity, clothing, utensils, bedding, pens and paper, kitchen conveniences, packaged foodstuffs, and access to the Internet. Therefore, how well you get along will always depend upon how well you work with others, even if you choose to take a chance and work alone.

*

Approximation is imprecise by definition. Often, however, there is more than one path to the same estimation.

Before the acquisition of McDonnell-Douglas, The Boeing Company had about 100,000 employees who produced about thirty commercial planes per month. If 60,000 of them were devoted to the construction of new airplanes and the rest were employed in the maintenance of existing aircraft or in other Boeing businesses, then it would have taken about 2,000 man months (60,000 employees ÷ 30 aircraft per month) to manufacture a new commercial airplane. That is about 167 man years per plane. However, the Boeing 777 is a larger, more complicated airplane than the 737, which makes up the bulk of Boeing production. By multiplying the 167 man-year average by 1.5 to reflect the greater complexity of the 777, we reach the same 250 man-year result.

We can also approach the problem from an economic view. Suppose, for instance, that we estimate the selling price of each 777 to be about $150,000,000. By rule of thumb, we also assume that about 50 percent of the price is the cost to manufacture, which would be around $75,000,000. Approximately 60 percent of the cost to build is likely to be parts, and the other 40 percent is likely to be labor. So the cost of labor to build a 777 is around $30,000,000. If Boeing’s fully loaded labor cost is around $60 per hour, then the total number of hours required to build a Boeing 777 is 500,000. Dividing 500,000 by 250 man days per year and 8 hours per man day (2,000) yields the number of man years estimated to build a 777, which, once again, is 250.

15

Why There Are Meetings

“All errors of consequence require collaboration.”

— JULIAN DATE

T

o make teamwork work, there is a recurring need to coordinate: to determine near-term objectives, to checkpoint progress, to brainstorm difficult solutions, to change course, to make sure everyone has the same news. In many such instances, one-to-one communications don’t always work. That is why meetings were invented. Many corporate veterans, however, believe that meetings are really a time-consuming management device that is used for the perpetuation of employee discord. For the sake of good morale, such beliefs should be examined from time to time, which is exactly what Cecilia Sharpe agreed to do just a short while ago.

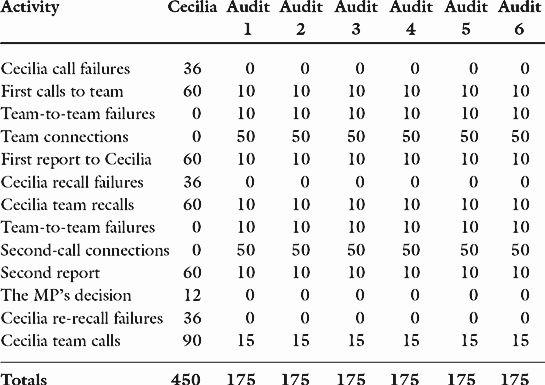

At the time, Cecilia was managing an audit team of six accountants who were closing the annual books for two large customers. Between the pressure of their work at

multiple customer sites and the usual office tasks, none of them felt they had the time to attend the hourlong progress meetings that took place every Friday. Cecilia, who has always been an excellent listener, agreed to eliminate the weekly meeting on an experimental basis in return for a commitment from each auditor to maintain direct communication with each and every other member of the team.

The very next Friday, Cecilia had to propose a revised work schedule to her auditing crew. Since they had fallen behind with one customer, the team had to decide whether to work ten hours per weekday until they caught up or to work Saturdays instead. Given the personal impact of the decision, Cecilia felt that each individual had to have the opportunity to voice an opinion and to hear the opinions of his or her peers.

Cecilia began to call the members of her team. She quickly discovered, however, that the probability of reaching any team member with one call was only 25 percent since there were several possible locations for each auditor, plus lunches, customer meetings, and travel between customer sites. Therefore, it took Cecilia twenty-four phone calls to reach all six members of the audit team.

The eighteen failed calls took only two minutes each. The six successful calls required an average of ten minutes each, during which time Cecilia and each accountant discussed the pros and cons of each proposal. At the end of the call, Cecilia asked that each auditor confer with each other before the end of business the following Tuesday, then get back to her with an opinion so that a timely decision could be made.

The next Monday, each team member commenced contacting each other. Because some were working in close

proximity, they managed to reach each other by the second call, on average. It took only ten minutes per call for each member to have his say. By Tuesday afternoon, every team member had talked to every other and had gotten back to Cecilia for a ten-minute discussion of their individual recommendations, a total of twenty-one distinct communications.

For a variety of personal reasons, four team members favored working longer weekdays and two team members favored working on Saturdays. Although there was a majority opinion, Cecilia was certain that they would never accept a split result in a typical weekly meeting without more discussion. The next day, a Wednesday, she contacted each member of the team again, which took an average of four calls each. During ten-minute discussions, she requested that each member again confer with each other to see if a clearer decision could be reached by the end of the next day.

The team members repeated the process, then each contacted Cecilia by Thursday evening as promised. After a ten-minute update with each of them, Cecilia found that two team members had indeed changed their votes. Four members now favored working on Saturdays, and two members preferred longer weekdays.

Exasperated and out of time, Cecilia consulted with the managing partner. A devotee of “The Solomon School of Management,” he instantly decided that the team would work nine-hour weekdays and half-day Saturdays. After the usual number of failed calls, Cecilia managed to inform each team member of her boss’s decision. Naturally, it took a little extra explaining.

While her team sulked, Cecilia calculated the accumulated

time it had taken to replace a one-hour meeting with person-to-person communications, as follows (in minutes):

Total time consumption was 1,500 minutes, or twenty-five person hours. A one-hour team meeting would have taken a total of seven person hours, so net lost productivity was eighteen hours. Moreover, each team member’s work had been interrupted an average of seventeen times, a total of 102 disruptions versus seven for a comparable meeting. The decision was two days late. No one was happy with the final result.

The very next day, which was a Friday, Cecilia’s team resumed its normal pattern of weekly get-togethers. Since then, the team has taken steps to improve meeting quality:

- An agenda is published at least one day before every meeting.

- Since a ten-minute delay caused by one thoughtless team member could result in seventy minutes of lost productivity and no small amount of irritation, every member of the team arrives on time.

- Every attendee sticks to the agenda.

- The meetings are concluded on time.

Once the pressure of the audit season was behind them, the managing partner asked Cecilia if she would like to repeat the test in order to confirm her results. Like any good boss who cared about the morale and productivity of her team, she graciously declined—on the spot.

16

Common Cause

“In every age and clime we see

Two of a trade can never agree.”

— JOHN GAY

S

ince every company employee is on the same team, since there are so many futures at stake, and since there are so many barriers to be constantly overcome, it would seem that common cause would be common in business. It isn’t.

A few years ago in Seattle, which is North America’s only urban rain forest, a team of loggers was called in to fell a huge cedar tree that prevented the construction of a new software laboratory. Shortly thereafter, a bulldozer was brought in to remove the stump, but the stump was so large and so deeply entrenched that the bulldozer could not budge it. The foreman in charge of tree extraction circled the stump, carefully considered the problem, checked his watch, then called in three more bulldozers.

The new drivers, all of whom were independent contractors in competition with each other, individually surveyed

the stump and the terrain upon arrival. Then each of the four bulldozer operators threw a chain around the stump, started up his bulldozer, threw it into low gear and commenced pulling.

On a hunch, the first bulldozer pulled toward the south. The second operator was convinced that he had a more powerful bulldozer than the first, so he pulled north. The third operator was certain that the stump was leaning toward the east, so he pulled in that direction. And the last operator was new to the profession and absolutely unwilling to work with any of the other three, so he pulled toward the west.

In the finest American tradition, each desperately wanted to defeat the others and succeed in pulling up the stump. So each operator pulled hard and each pulled long. Since each bulldozer had a two-hundred-horsepower engine, a large quantity of energy was expended in the effort. But the stump remained unmoved.

The foreman could see the problem. But he had started a small betting pool on the competition, and the loggers, big-shouldered men who did not like to be disappointed, had already placed their wagers. So rather than redirect the efforts of the bulldozers, the foreman doubled the quantity of gasoline and exhorted all four operators to try harder. Hours passed. Bulldozers strained against the load. Exhaust fumes filled the air. The foreman observed and exhorted. The loggers alternately cheered, booed, and did the wave. But still the stump was unmoved. Some time after darkness fell, they all reached a consensus to try again the following day.