The Arithmetic of Life and Death (20 page)

Read The Arithmetic of Life and Death Online

Authors: George Shaffner

Tags: #Philosophy, #Movements, #Phenomenology, #Pragmatism, #Logic

If, for instance, Gwen’s father can make it to age eighty, then his odds of making it to age eighty-one are better than 92 percent (100 percent—7.644 percent = 92.356 percent).

In order to reach eighty, though, he will probably have to quit smoking and start exercising. On the other hand, if Cecilia can make it to age eighty, then her odds of getting to age eighty-one are better than 96 percent. And she doesn’t smoke.

According to the National Funeral Directors Association, about 2,294,000 people died in the year 1997. Presumably, none of them was you. Although the annual American death toll will rise to approximately 3,472,000 in the year 2030, the odds are against your death in any one of those years, at least until you reach the age of 115, after which your odds of death in any one year are about 50/50 until the actual event.

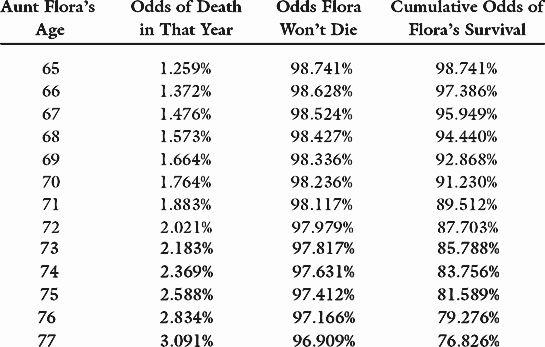

However, the accumulation of the odds of death are still likely to prevent you from reaching 115. If you were a woman born in 1933 like Gwen’s aunt Flora, for instance, then you were sixty-five years old in 1998, and the odds that you would die in 1999 were just 1.26 percent. But the chances that you would die the following year were 1.37 percent, and 1.48 percent the year after that. After a while, all of those small percentages begin to add up, as follows:

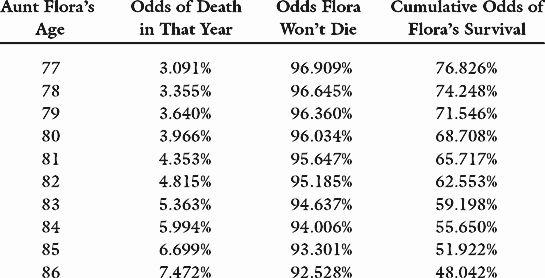

All things being equal, Aunt Flora has a better than three in four chance of living to exceed the average life expectancy of babies born in 1998. However, Aunt Flora cannot be expected to live to age 115, when her chances of dying in a single year are about 50 percent. That is because her future odds of death will continue to accumulate:

When Aunt Flora actually succumbs is a matter of speculation. To a large extent, it will be dependent on her age and her genetic makeup. But it will also be a matter of diet, habit, exercise, and frame of mind, meaning that Flora will have the opportunity to influence her life expectancy to a

considerable extent. This is an opportunity that we all share. If, for instance, you wish to die sooner than your birth-year counterparts, then you might consider:

- being a man, especially with a history of heart disease in the immediate family;

- becoming obese and staying that way;

- smoking cigarettes with regularity and abusing alcohol and other drugs;

- choosing a high-stress occupation, such as a criminal or inner-city arms dealer; and

- having unprotected sex with as many people as possible.

Life, however, is a gift. If you wish to honor the gift by living life to its fullest, which even the lowliest of sea creatures are intelligent enough to do, then you might consider:

- being or behaving like a woman (see “Death by Misadventure”);

- eating a balanced diet rich in water, vitamins, minerals, and fiber;

- exercising regularly;

- getting an annual medical checkup; and

- owning pets (especially cuddly ones), which lowers the blood pressure of their owners and provides a general sense of well-being.

If you choose to work at postponing your death, then you have a decent chance of living beyond the age of

eighty-five. In 1990, there were three million Americans who had surpassed that advanced age. By 1998, the total had increased to more than four million.

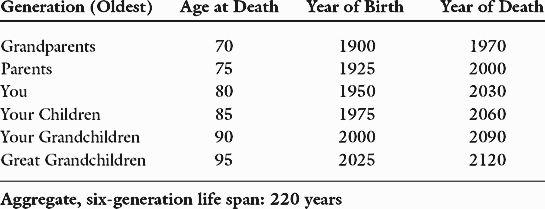

All over the world, people are living longer than at any time in the history of man. You are likely (although not certain) to live longer than your parents, who probably lived longer than their parents. Your children are likely (but not certain) to live longer than you. It is, in fact, quite possible that your lifetime will span six generations:

Although we may expect our lives to last only eighty years, that may be enough to touch more than two centuries of history. Indeed, there were men and women in the time of the Civil War whose grandparents were alive during the Revolutionary War and whose great-grandchildren may have fought in Korea. That means that they had an opportunity to have a personal discussion with nearly two hundred years of armed conflict.

There are children being born at the end of the twentieth century who should not expect it but who will live to see the dawn of the twenty-second century. Their great-grandparents may have been alive during World War I; their grandparents may have fought in World War II; their

parents may have protested Vietnam. Let us hope, however, that the children of the twenty-first century will have learned from us, the children of the twentieth, the meaning of the word futility. If so, then they will mark their time not by conflict, but by the peaceful advance of the human spirit.

32

The Preservation of Prejudice

“Rancor is an outpouring of a feeling of inferiority.”

— JOSÉ ORTEGA Y GASSET

P

rejudice has served our nation well for many, many years. It permitted us to confiscate much of the land we call the United States from its previous inhabitants; it allowed us to establish a large, agrarian economy based upon free labor; it furnished us with the most devastating war in our history; and, to this day, it provides us with a steady diet of distrust, discomfort, hate, fear, and loathing.

Historically, America’s best and most persevering prejudices have been founded on skin color. This is no accident. Basing bigotry on race has a number of important advantages:

- Everybody has a skin color.

- Except for a famous exception or two, it is determined at birth.

- It can be seen at a considerable distance.

- For a very long time, we have had a clear majority of one color, which has been the key to the practice of safe prejudice in the United States.

- Skin color is arbitrary—meaning that no reliable inferences on anything of value, including ethic, compassion, or social contribution, can be drawn solely from it.

Actually, the last point is not completely true. The amount of melanin in the skin determines both its color and its owner’s ability to resist harm from overexposure to the sun. Basically, the more melanin you have, the better protected you are—and the darker-skinned you are. However, from the perspective of prejudice, which dates back to the Egyptian pharaohs, this is a recent discovery. And it’s a pretty minor point.

Otherwise, no study by a responsible academic or government institution has ever been able to prove any general inferiority or superiority of race based on skin color. This is because a generality can be true in math and logic if and only if there are no exceptions. For instance, there are no exceptions to 2 + 2 = 4. But there are millions of exceptions to “Asian people are smarter than white people.” Therefore, no generality can be made, other than “Some Asian people are smarter than some white people, and some white people are smarter than some Asian people.”

What has been proven, in general, is that the correlation between the amount of melanin in human skin and the quantity and density of convolutions in the human brain is zero. Zilch. Nada. Nil. So, regardless of your color, you can never tell whether the next person you meet is either

smarter or dumber than you are, regardless of their color. The same is true for every other measurable trait known to mankind, and for all of the immeasurable ones as well.

If you are still having a hard time catching on, then perhaps an example will help. If you are a white supremacist, who would you rather invite to your next family barbecue, Colin Powell or John Wayne Gacy? If you are a black supremacist, would you rather invite Gloria Estefan or Idi Amin? If an Asian supremacist, Maya Angelou or Pol Pot? If an Hispanic supremacist, Steven Spielberg or Augusto Pinochet?

The moment you waver, even for a split second, any racial generality is dead.

However, you still can be arbitrary. From the perspective of perpetuation of prejudice, this is critically important. If any form of racial inferiority had ever been proven, then from that moment forward, continued fear and loathing would have been impossible. How could any intelligent being reasonably fear another who had been proven to be weaker or less intelligent? How could any compassionate being reasonably loathe another who was in obvious need of charity and patience?

Luckily, bigotry based upon skin color is about as arbitrary as can be. However, despite its historic advantages, race-based prejudice is beginning to break down. The United States is getting too diverse. It’s getting too hard to tell who is what. There are just too many shades of brown.

What are all those East Indians from India? And, by the way, why isn’t their skin color more consistent? And what about all those Polynesians? What are they? How about South Americans? Are they Hispanic or Native American or both or something else? What are Arabs: white, cream-colored,

beige, sandstone? Are North Africans black or Arab or French or what? What is a Filipino or practically anybody from the Caribbean? And how does one classify a deeply tanned white or Asian person, other than as insufficiently busy?

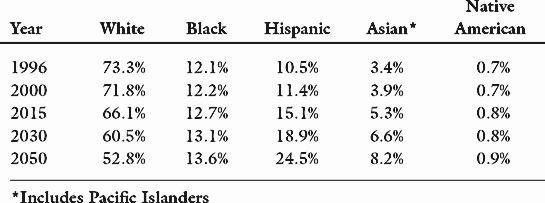

Worse, the numbers are beginning to deteriorate. America’s white majority is in retreat:

Forecast U.S. Racial Composition by Percentage