The Art and Craft of Coffee (5 page)

Read The Art and Craft of Coffee Online

Authors: Kevin Sinnott

Laos produces Liberica, a rare commodity coffee said to make a distinctive espresso coffee. It can take a variety of roasts. Laotian coffee is difficult to find, although on occasion, a smattering goes to home roasters via online auctioneers.

Vietnam

Vietnam produces a huge amount of commodity coffee but no specialty coffee. The vast majority of its crop is Robusta, no doubt a strategic decision to capitalize on its position behind Brazil as the second largest coffee producer.

Indonesia and Oceania

Indonesian coffees are generally big-boned, flavorful coffees with huge body and a subtle acidity. Even the beans themselves can be oversized. These coffees may be best defined as big but never bland.

Hawaii

Hawaii has great volcanic soil, but historically Hawaiians placed more importance on sugar plantations. To the United States, sugar cane was a worthier investment than coffee.

Sumatra coffee trees amidst taller shade trees.

Hawaii has a good climate and volcanic soil. There is some fine coffee grown there. But, demand is so high that in the 1990s a scandal rocked the coffee world involving coffee imported from Costa Rica that was simply re-labeled Kona.

There isn’t enough great Kona. Its wine flavor rivals the best Kenyan, and its subterranean body approaches the best Jamaican Blue Mountain.

If buying for roasting, start light and go just deep enough to Full City. Roast any darker and you’ll lose the acidity. Use the same advice for buying Kona, although most pure Kona is roasted fairly light.

Sumatra

A high-humidity climate, volcanic soil, and dated ancient processing methods make Sumatra one of the most satisfying coffees. It has historically been underrated. Sumatran coffee was once sold as Javan, and the best Javan grade at that. Most of the finest Mocha-Java blends were likely Sumatran coffee as well. The gap widened even further when a leaf rust disease destroyed most good Javan coffee but skipped Sumatra altogether.

Expect a good to colossal body. At its best, Sumatran coffee also has a muted spicy acidity that lingers at the back of the mouth. Mandheling and Lintong are two famous districts. The original vintage Sumatra taste depends on dry processing, though some wet processed coffees have the same profile. If buying green to roast, don’t over-roast.

Sumatra Variant: Kopi

This famous Sumatra coffee is fed to an Indonesian mammal called a civet and retrieved post-digestion. Despite its source, Kopi coffee is quite good, but it’s expensive. If you get the chance, try Kopi. You’ll be surprised by its body and acidity.

Sulawesi

In a quick taste snapshot, Sulawesi appears a refined Sumatran with more acidity, less body, and a cleaner, if sometimes less distinctive taste.

Sulawesi seems a more consistent coffee than Sumatran. Whether this is due to farming practices, processing, industry, climate, or other conditions is unknown, but many in the industry say they buy Sulawesi coffees with more assurance than Sumatrans. A noted coffee shop owner once said, “Sulawesi coffee is Sumatra coffee with all its problems fixed.”

Sulawesi is often labeled Celebes, which is not a region but actually the island’s original name. Reportedly, the best Sulawesi coffee comes from Toraja, a mountain in the island’s center.

Papua New Guinea

If Sulawesi is a refined Sumatran, Papua New Guinea might be considered a refined Sulawesi. It has the highest acidity of the Indonesian coffees. The balance definitely tilts upward, meaning more pronounced acidity than body—a rarity for Pacific coffees. The region generally practices wet processing, though some farms dry process.

MOCHA DISTINCTIONS

Mocha is one of the coffee world’s most commonly used words. It denotes beans grown in Yemen. Sometimes, neighboring Ethiopian (and even Brazilian) beans receive the Mocha label, an inaccuracy dating from coffee’s casual labeling history. Today, the term also describes chocolate, hence its use to describe an espresso beverage made with chocolate flavoring, and a European mildly pressurized drip method. The latter is spelled Moka.

Yemen

Yemen coffee causes endless arguments among coffee connoisseurs. It is old and its coffee-growing culture breaks all the rules, yet it is still revered as one of the best varieties. It is grown almost at sea level and is almost all dry processed, irregularly and often sloppily. The beans all look different and have a decidedly ragged appearance. It’s part of the processing and not necessarily indicative of a quality problem.

But amidst the broken beans, insect damage, mold, and other artifacts, the coffee displays so much flavor balance and complexity that it is easy to taste why Yemen’s coffee business flourishes. If you want perfectly shaped, even-colored beans, don’t try Yemen coffee. But if it’s taste you want, the small irregular beans provide coffee unlike any other.

Yemen is all Bourbon and almost certainly organic, although it is rarely certified. Good beans come from all over Yemen, with much of it from the country’s cottage industry, grown on small plots behind houses and dried on rooftops. It blends perfectly with Javan or Sumatran coffee.

When buying green, expect less-than-perfect appearance. Resist the urge to over-roast to create a more uniform appearance. If buying roasted, don’t be afraid of a less-than-uniform looks. The best tasting Yemen Mocha can look uneven and be roasted light. Yemen will also take a dark roast and is overall a flexible coffee.

>

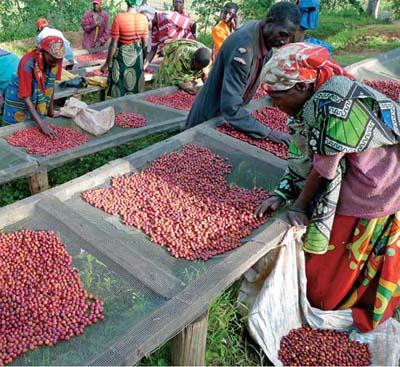

This coffee is sorted by hand, an important step in quality control.

Africa

The African continent’s coffees are definitive; anything else is a variation. African coffees tend to be wine-like, with good but not overly present bodies. Some of the world’s smallest beans come from Africa, but they have intensely concentrated flavor.

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

The DRC (formerly Zaire) produces some fine coffees, but they are not widely available so the country has little name recognition.

Ethiopia

This widely accepted coffee birthplace has a long, mostly unblemished history. The commodity coffee trade brought the bean to other countries, where factory plantation methods ruined it. But Ethiopia kept its fine growing and processing traditions.

Dry processing creates the best Ethiopian coffees. The coffee, typically full-bodied with a light fruitiness, exhibits two main taste footprints called Harrar and Sidamo/Yirga Chefe. Harrar has a cleaner taste, a lighter body, and a decided blueberry note. Sidamo is spicy. Yirga Chefe, a city within Sidamo province, markets its coffee by its town name (the only noticeable difference between Yirga Chefe and Sidamo).

Ethiopian coffee is inconsistent. Labeling problems make it frustrating to find the same coffee flavor twice. If you come across one you like, grab it. If roasting, err on the side of light roasts.

Kenya

Kenyan is the most famous non-Arab African coffee. The country also has one of the world’s most modern coffee industries, probably because it planted coffee late. It was the first coffee country to adopt a reasonable grading system that addresses coffee quality. Kenya AA is the highest. The best Kenyan coffee comes from Mount Kenya.

All Kenyan coffees are wet-processed and most likely Caturra. Kenyan coffee is wine-like and full bodied, but it’s distinctive with unique blackberry notes.

Rwanda

Rwandan coffee has a high acidity and full body. Though Rwandan coffee is known for being washed, its dry-processed versions (though rare) are stellar.

Tanzania

Tanzanian coffee, which grows on Mounts Kilimanjaro and Meru, tastes much like a good Kenyan, with the same African wine-like footprint. Some Tanzanian coffees taste like Ethiopian coffee.

Uganda

Uganda has created some great coffee on mountains near Kenya, but the country does not produce large quantities. That it does produce gets lost in the mainstream specialty business. If roasting, don’t roast too far.

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwean coffee has little name recognition, though it offers a rich body and nice balance. It has the same winey acidity as a Kenyan, without the blackberry note. Even so, more than one commercial coffee roasting company has labeled Zimbabwean coffee Kenyan to sell it at a higher price. Some of the best Zimbabwean coffee comes from the town of Chipinge under a Salimba label.

Additional Coffee-Buying Considerations

The coffee world is changing. Even the most careful listing of regions and coffees won’t offer you an exact roadmap. Thanks to direct trade, the World Wide Web, and small family farms, we now have much greater access to high-quality coffees that defy categorization.

When choosing a variety, ask yourself these questions:

1. How does it smell? If it’s green and for roasting, how fresh is it?

2. What genus of bean is it?

3. Is it from a small farm? Does my coffee buyer know anything about the farm’s methods?

Pay less attention to whether it’s organic, bird-friendly/shade grown, or fair-traded (unless it’s commodity coffee).

The rubber meets the road in the coffee seller’s shop. Use varieties as a starting point. But before simply deciding based on geography, ask questions. It’s better to buy a great coffee from an unknown or underappreciated region (e.g., Nicaragua) than a mediocre coffee from a well-known one (e.g., Sumatra). Most regional differences are wider ranging than even coffee buyers assume. I have tasted great coffee from almost every world region and country. If I haven’t, I assume it’s because I have not run into it yet. I never rule out new varieties. Neither should you.

Taste Comes First

I know I may get flak for downplaying environmental sustainability and labor issues. I agree with these goals in spirit, but I sincerely believe that any product sold primarily for taste must taste good first. With coffee, aroma comes in a close second. In fact, you almost can’t separate coffee’s taste and aroma. Fortunately, most environmental, sustainability, and labor issues lead to good-flavored coffee.

Also, geography isn’t everything. It is important to understand geographic coffee-growing regions because so much of flavor depends on terroir. But the increase of micro-lots farmed and processed by individuals complicates the equation. For example, a farm in Honduras recently began selling coffee from plant cuttings brought from Ethiopia. Startlingly, this coffee tastes more Ethiopian than other Honduran coffees. Is the earth less important than previously assumed?

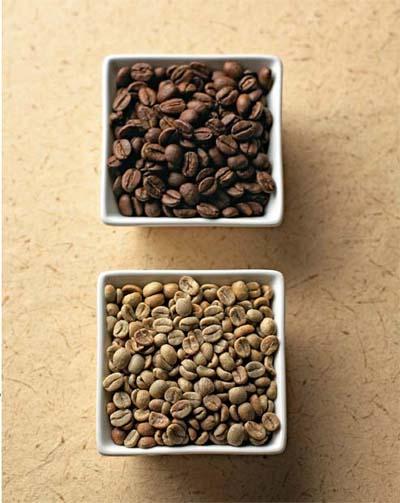

Where the bean originated still carries authority when predicting taste. The most important decision when taking a photograph is choosing a worthy subject. In the case of coffee beans, the first step is finding beans worth turning into coffee.