The Art of Manliness - Manvotionals: Timeless Wisdom and Advice on Living the 7 Manly Virtues (13 page)

Authors: Brett McKay

“Be regular and orderly in your daily affairs that you may be violent and original in your work.” —Gustave Flaubert

Theodore Roosevelt and Benjamin Franklin

In the introduction to this chapter, we detailed how much two great men from history, Benjamin Franklin and Theodore Roosevelt, accomplished during their lives. One of the secrets to their inspiring success was the way in which they effectively utilized their time each day. For a closer examination of just how they did this, here is a look at each man’s daily schedule.

ENJAMIN

F

RANKLIN’S

D

AILY

S

CHEDULE

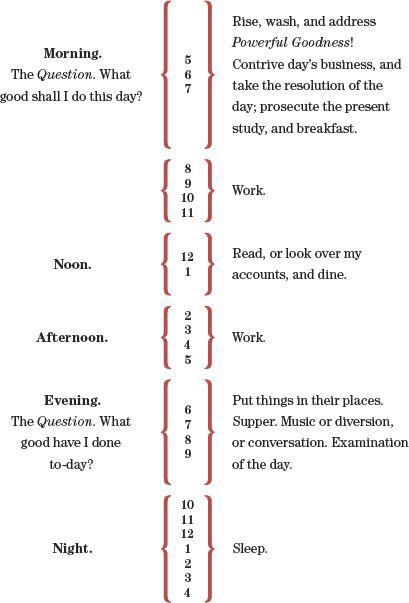

Seeking to attain “moral perfection,” Benjamin Franklin established a program in which he strove to live thirteen different virtues. As he particularly struggled with the “precept of Order,” he kept the following schedule inside the little notebook in which he kept track of his adherence to the virtues.

HEODORE

R

OOSEVELT’S

D

AILY

S

CHEDULE

When campaigning for the vice presidency in 1900, TR spent eight weeks barnstorming around the country. Traveling by train, he covered 21,000 miles visiting twenty-four states. All along the way he made speeches, delivering 700 in all to 3 million people.

His daily schedule during this time was recorded by a man who accompanied him on the tour.

7:00 A.M.—Breakfast.

7:30 A.M.—A speech.

8:00 A.M.—Reading a historical work.

9:00 A.M.—A speech.

10:00 A.M.—Dictating letters.

11:00 A.M.—Discussing Montana mines.

11:30 A.M.—A speech.

12:00 P.M.—Reading an ornithological work.

12:30 P.M.—A speech.

1:00 P.M.—Lunch.

1:30 P.M.—A speech.

2:30 P.M.—Reading Sir Walter Scott.

3:00 P.M.—Answering telegrams.

3:45 P.M.—A speech.

4:00 P.M.—Meeting the press.

4:30 P.M.—Reading.

5:00 P.M.—A speech.

6:00 P.M.—Reading.

7:00 P.M.—Supper.

8:00 to 10:00 P.M.—Speaking.

11:00 P.M.—Reading alone in his car.

12:00 P.M.—To bed.

F

ROM

“T

HE

P

OWERS OF A

S

TRENUOUS

P

RESIDENT,

” 1908

By “K”

The following excerpt from an article in

The American Magazine

illuminates the way in which Roosevelt’s energy and discipline made this kind of extraordinary productivity possible.

The President is the very incarnation of order and regularity in his work. That is part of his system of energizing. Every morning Secretary Loeb places a typewritten list of his engagements for the day on his desk, sometimes reduced to five-minute intervals. And no railroad engineer runs more sharply upon his schedule than he. His watch comes out of his pocket, he cuts off an interview, or signs a paper, and turns instantly, according to his time-table, to the next engagement. If there is an interval anywhere left over he chinks in the time by reading a paragraph of history from the book that lies always ready at his elbow or by writing two or three sentences in an article on Irish folk-lore, or bear-hunting.

Thus he never stops running, even while he stokes and fires; the throttle is always open; the engine is always under a full head of steam. I have seen schedules of his engagements which showed that he was constantly occupied from nine o’clock in the morning, when he takes his regular walk in the White House Park with Mrs. Roosevelt, until midnight, with guests at both luncheon and dinner. And when he goes to bed he is able to disabuse his mind instantly of every care and worry and go straight to sleep, and he sleeps with perfect normality and on schedule time.

I have been thinking back over Roosevelt’s career in the White House and I cannot now remember to have heard that he was ever ill or even indisposed as other men sometimes are. Like any good engineer, he keeps his machinery in such excellent condition that he never has a breakdown.

Thus we have the spectacle of a man of ordinary abilities who has succeeded through the simple device of self-control and self-discipline, of using every power he possesses to its utmost limit.

“Let us realize that the privilege to work is a gift, that power to work is a blessing, that love of work is success.” —David O. McKay

A

N

A

ESOP’S

F

ABLE

A Farmer being on the point of death, and wishing to show his sons the way to success in farming, called them to him, and said, “My children, I am now departing from this life, but all that I have to leave you, you will find in the vineyard.” The sons, supposing that he referred to some hidden treasure, as soon as the old man was dead, set to work with their spades and ploughs and every implement that was at hand, and turned up the soil over and over again. They found indeed no treasure; but the vines, strengthened and improved by this thorough tillage, yielded a finer vintage than they had ever yielded before, and more than repaid the young husbandmen for all their trouble.

Industry is in itself a treasure.

“It is better to wear out than to rust out.” —Bishop Richard Cumberland

F

ROM

R

EADINGS FOR

Y

OUNG

M

EN,

M

ERCHANTS, AND

M

EN OF

B

USINESS

, 1859

“Now” is the constant syllable ticking from the clock of Time. “Now” is the watchword of the wise. “Now” is on the banner of the prudent. Let us keep this little word always in our mind; and, whenever any thing presents itself to us in the shape of work, whether mental or physical, we should do it with all our might, remembering that “now” is the only time for us. It is indeed a sorry way to get through the world by putting off till to-morrow, saying, “then” I will do it. No! This will never answer. “Now” is ours; “Then” may never be.

“Industry is the enemy of melancholy.” —William F. Buckley Jr.

F

ROM

N

ICOMACHEAN

E

THICS

, c. 350 B.C.

By Aristotle

We do not labor that we may be idle; but, as Anarchis justly said, we are idle that we may labor with more effect; that is, we have recourse to sports and amusements as refreshing cordials after contentious exertions, that, having reposed in such diversions for a while, we may recommence our labors with increased vigor. The weakness of human nature requires frequent remissions of energy; but these rests and pauses are only the better to prepare us for enjoying the pleasures of activity. The amusements of life, therefore, are but preludes to its business, the place of which they cannot possibly supply; and its happiness, because its business, consists in the exercise of those virtuous energies which constitute the worth and dignity of our nature. Inferior pleasures may be enjoyed by the fool and the slave as completely as by the hero or the sage. But who will ascribe the happiness of a man to him, who by his character and condition, is disqualified for manly pursuits?

F

ROM

B

ALLADS AND

O

THER

P

OEMS

, 1841

By Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

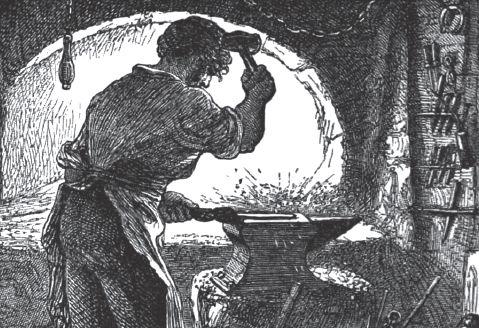

Under a spreading chestnut tree

The village smithy stands;

The smith, a mighty man is he,

With large and sinewy hands;

And the muscles of his brawny arms

Are strong as iron bands.

His hair is crisp, and black, and long,

His face is like the tan;

His brow is wet with honest sweat,

He earns whate’er he can,

And looks the whole world in the face,

For he owes not any man.

Week in, week out, from morn till night,

You can hear his bellows blow;

You can hear him swing his heavy sledge,

With measured beat and slow,

Like a sexton ringing the village bell,

When the evening sun is low.

And children coming home from school

Look in at the open door;

They love to see the flaming forge,

And hear the bellows roar,

And catch the burning sparks that fly

Like chaff from a threshing floor.

He goes on Sunday to the church,

And sits among his boys;

He hears the parson pray and preach,

He hears his daughter’s voice,

Singing in the village choir,

And it makes his heart rejoice.

It sounds to him like her mother’s voice,

Singing in Paradise!

He needs must think of her once more,

How in the grave she lies;

And with his hard, rough hand he wipes

A tear out of his eyes.

Toiling,—rejoicing,—sorrowing,

Onwards through life he goes;

Each morning sees some task begin,

Each evening sees it close;

Something attempted, something done,

Has earned a night’s repose.

Thanks, thanks to thee, my worthy friend,

For the lesson thou hast taught!

Thus at the flaming forge of life

Our fortunes must be wrought;

Thus on its sounding anvil shaped

Each burning deed and thought!

“It is not enough to be industrious; so are the ants. What are you industrious about?” —Henry David Thoreau

F

ROM

T

RAITS OF

C

HARACTER

, 1898

By Henry F. Kletzing

A light snow had fallen and a company of schoolboys wished to make the most of it. It was too dry for snowballing. It was proposed that a number of boys walk across a meadow near by and see who could make the straightest track. On examination it was found that only one could be called straight. When asked, two of them said they went as straight as they could without looking at anything but the ground. The third said, “I fixed my eye on that tree on yonder hill and never looked away till I reached the fence.”

We often miss the end of life by having no object before us.