The Art of Manliness - Manvotionals: Timeless Wisdom and Advice on Living the 7 Manly Virtues (20 page)

Authors: Brett McKay

I know not how to aid you, save in the assurance of one of mature age, and much severe experience, that you

can

not fail, if you resolutely determine, that you

will

not.

The President of the institution, can scarcely be other than a kind man; and doubtless he would grant you an interview, and point out the readiest way to remove, or overcome, the obstacles which have thwarted you.

In your temporary failure there is no evidence that you may not yet be a better scholar, and a more successful man in the great struggle of life, than many others, who have entered college more easily.

Again I say let no feeling of discouragement prey upon you, and in the end you are sure to succeed.

With more than a common interest I subscribe myself.

Very truly your friend,

A. Lincoln.

F

ROM THE ESSAY

“O

N

P

ROVIDENCE,

” IN

T

HE

M

INOR

D

IALOGUES

, c. 60–65 A.D.

By Seneca

In this essay, Seneca gives the Stoic explanation for why the gods allow bad things to happen to good people. His answer? What seems like hardship is really for our good; adversity tests and strengthens us and allows us to demonstrate our virtue.

Prosperity comes to the mob, and to low-minded men as well as to great ones; but it is the privilege of great men alone to send under the yoke the disasters and terrors of mortal life: whereas to be always prosperous, and to pass through life without a twinge of mental distress, is to remain ignorant of one half of nature. You are a great man; but how am I to know it, if fortune gives you no opportunity of showing your virtue?

You have entered the arena of the Olympic games, but no one else has done so: you have the crown, but not the victory: I do not congratulate you as I would a brave man, but as one who has obtained a consulship or praetorship. You have gained dignity. I may say the same of a good man, if troublesome circumstances have never given him a single opportunity of displaying the strength of his mind. I think you unhappy because you never have been unhappy: you have passed through your life without meeting an antagonist: no one will know your powers, not even you yourself.

For a man cannot know himself without a trial: no one ever learnt what he could do without putting himself to the test; for which reason many have of their own free will exposed themselves to misfortunes which no longer came in their way, and have sought for an opportunity of making their virtue, which otherwise would have been lost in darkness, shine before the world. Great men, I say, often rejoice at crosses of fortune just as brave soldiers do at wars. I remember to have heard Triumphus, who was a gladiator in the reign of Tiberius Caesar, complaining about the scarcity of prizes. “What a glorious time,” said he, “is past.”

Valour is greedy of danger, and thinks only of whither it strives to go, not of what it will suffer, since even what it will suffer is part of its glory. Soldiers pride themselves on their wounds, they joyously display their blood flowing over their breastplate. Though those who return unwounded from battle may have done as bravely, yet he who returns wounded is more admired.

Do not, I beg you, dread those things which the immortal gods apply to our minds like spurs: misfortune is virtue’s opportunity. Those men may justly be called unhappy who are stupified with excess of enjoyment, whom sluggish contentment keeps as it were becalmed in a quiet sea: whatever befalls them will come strange to them. Misfortunes press hardest on those who are unacquainted with them: the yoke feels heavy to the tender neck. The recruit turns pale at the thought of a wound: the veteran, who knows that he has often won the victory after losing blood, looks boldly at his own flowing gore.

Avoid luxury, avoid effeminate enjoyment, by which men’s minds are softened, and in which, unless something occurs to remind them of the common lot of humanity, they lie unconscious, as though plunged in continual drunkenness. He whom glazed windows have always guarded from the wind, whose feet are warmed by constantly renewed fomentations, whose dining-room is heated by hot air beneath the floor and spread through the walls, cannot meet the gentlest breeze without danger. While all excesses are hurtful, excess of comfort is the most hurtful of all; it affects the brain; it leads men’s minds into vain imaginings; it spreads a thick cloud over the boundaries of truth and falsehood.

Why then should we wonder if God tries noble spirits severely? There can be no easy proof of virtue. Fortune lashes and mangles us: well, let us endure it: it is not cruelty, it is a struggle, in which the oftener we engage the braver we shall become. The strongest part of the body is that which is exercised by the most frequent use: we must entrust ourselves to fortune to be hardened by her against herself: by degrees she will make us a match for herself. Familiarity with danger leads us to despise it. Thus the bodies of sailors are hardened by endurance of the sea, and the hands of farmers by work; the arms of soldiers are powerful to hurl darts, the legs of runners are active: that part of each man which he exercises is the strongest.

No tree which the wind does not often blow against is firm and strong; for it is stiffened by the very act of being shaken, and plants its roots more securely: those which grow in a sheltered valley are brittle: and so it is to the advantage of good men, and causes them to be undismayed, that they should live much amidst alarms, and learn to bear with patience what is not evil save to him who endures it ill.

“Fight one more round. When your arms are so tired that you can hardly lift your hands to come on guard, fight one more round. When your nose is bleeding and your eyes are black and you are so tired that you wish your opponent would crack you one on the jaw and put you to sleep, fight one more round—remembering that the man who fights one more round is never whipped.” —James “Gentleman Jim” Corbett, heavyweight boxing champion

By S.E. Kiser

I fight a battle every day

Against discouragement and fear;

Some foe stands always in my way,

The path ahead is never clear!

I must forever be on guard

Against the doubts that skulk along;

I get ahead by fighting hard,

But fighting keeps my spirit strong.

I hear the croakings of Despair,

The dark predictions of the weak;

I find myself pursued by Care,

No matter what the end I seek;

My victories are small and few,

It matters not how hard I strive;

Each day the fight begins anew,

But fighting keeps my hopes alive.

My dreams are spoiled by circumstance,

My plans are wrecked by Fate or Luck;

Some hour, perhaps, will bring my chance,

But that great hour has never struck;

My progress has been slow and hard,

I’ve had to climb and crawl and swim,

Fighting for every stubborn yard,

But I have kept in fighting trim.

I have to fight my doubts away,

And be on guard against my fears;

The feeble croaking of Dismay

Has been familiar through the years;

My dearest plans keep going wrong,

Events combine to thwart my will,

But fighting keeps my spirit strong,

And I am undefeated still!

“This is the test of your manhood: How much is there left in you after you have lost everything outside of yourself?” —Orison Swett Marden

to Choose One’s Own Way

F

ROM

M

AN’S

S

EARCH FOR

M

EANING

, 1959

By Viktor Frankl

In 1942, Jewish psychiatrist Viktor Emil Frankl, along with his wife and parents, were taken to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. There Frankl put his expertise to use in helping other prisoners deal with their grief and despair. At the same time, his own suffering led him to explore the meaning of life and how to find that meaning even in the midst of soul-crushing adversity.

In spite of all the enforced physical and mental primitiveness of the life in a concentration camp, it was possible for spiritual life to deepen. Sensitive people who were used to a rich intellectual life may have suffered much pain (they were often of a delicate constitution), but the damage to their inner selves was less. They were able to retreat from their terrible surroundings to a life of inner riches and spiritual freedom. Only in this way can one explain the apparent paradox that some prisoners of a less hardy makeup often seemed to survive camp life better than did those of a robust nature. In order to make myself clear, I am forced to fall back on personal experience. Let me tell what happened on those early mornings when we had to march to our work site.

There were shouted commands: “Detachment, forward march! Left-2-3-4! Left-2-3-4! Left-2-3-4! Left-2-3-4! First man about, left and left and left and left! Caps off!” These words sound in my ears even now. At the order “Caps off!” we passed the gate of the camp, and searchlights were trained upon us. Whoever did not march smartly got a kick. And worse off was the man who, because of the cold, had pulled his cap back over his ears before permission was given.

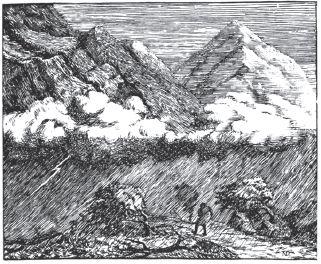

We stumbled on in the darkness, over big stones and through large puddles, along the one road leading from the camp. The accompanying guards kept shouting at us and driving us with the butts of their rifles. Anyone with very sore feet supported himself on his neighbor’s arm. Hardly a word was spoken; the icy wind did not encourage talk. Hiding his mouth behind his upturned collar, the man marching next to me whispered suddenly: “If our wives could see us now! I do hope they are better off in their camps and don’t know what is happening to us.”

That brought thoughts of my own wife to mind. And as we stumbled on for miles, slipping on icy spots, supporting each other time and again, dragging one another up and onward, nothing was said, but we both knew: each of us was thinking of his wife. Occasionally I looked at the sky, where the stars were fading and the pink light of the morning was beginning to spread behind a dark bank of clouds. But my mind clung to my wife’s image, imagining it with an uncanny acuteness. I heard her answering me, saw her smile, her frank and encouraging look. Real or not, her look was then more luminous than the sun which was beginning to rise.

A thought transfixed me: for the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth—that love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart:

The salvation of man is through love and in love.

I understood how a man who has nothing left in this world still may know bliss, be it only for a brief moment, in the contemplation of his beloved. In a position of utter desolation, when man cannot express himself in positive action, when his only achievement may consist in enduring his sufferings in the right way—an honorable way—in such a position man can, through loving contemplation of the image he carries of his beloved, achieve fulfillment. For the first time in my life I was able to understand the meaning of the words, “The angels are lost in perpetual contemplation of an infinite glory.”

In front of me a man stumbled and those following him fell on top of him. The guard rushed over and used his whip on them all. Thus my thoughts were interrupted for a few minutes. But soon my soul found its way back from the prisoner’s existence to another world, and I resumed talk with my loved one: I asked her questions, and she answered; she questioned me in return, and I answered.