The Articulate Mammal (17 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

Throughout the babbling period Barbara seemed to enjoy experimenting with her mouth and tongue. She not only babbled, she blew bubbles, gurgled and spluttered. Superficially, she appeared to be uttering an enormous variety of exotic sounds. At one time, researchers wrongly assumed that children are naturally capable of producing every possible speech sound. A Canadian psychologist once commented:

During this period, that peculiarly charming infantile babble begins, which, though only an ‘awkward twittering’, yet contains in rudimentary form nearly all the sounds which afterwards, by combination, yield the potent instrument of speech. A wonderful variety of sounds, some of which afterwards give the child difficulty when he tries to produce them, are now produced automatically, by purely impulsive exercise of the vocal muscles.

(Tracy 1909, in Bar-Adon and Leopold 1971: 32)

More recent investigators have noted that the variety of sounds used in babbling is not particularly great. But because the child does not yet have complete control over his vocal organs, the noises are often unlike adult sounds, and seem exotic to an untrained observer. In general, babbling seems to be a period when a child experiments and gradually gains muscular control over his vocal organs. Many people claim that babbling is universal. But there are a few puzzling records of children who did not babble, which provide problems for this point of view. All we can say at the moment is that

babbling is sufficiently widespread to be regarded as a normal stage of development.

Some investigators have tried to compare babbling babies who have been exposed to different languages. For example, Chinese babbles seem to be easily distinguishable from American, Russian and Arabic ones (Weir 1966). Because Chinese is a language which distinguishes words by means of a change in ‘tone’ or ‘pitch’, Chinese babies tend to produce monosyllabic utterances with much tonal variation. American babies produce polysyllabic babbles with intonation spread over the whole sequence. The non-tone babies sound superficially similar – though American mothers could often pick out the American baby, Russians the Russian baby, and Arabs the Arab baby. But the mothers could not distinguish between the babies babbling the other two languages. This research indicates that there may be a ‘babbling drift’, in which children’s babbling gradually moves in the direction of the sounds they hear around them. These findings have been confirmed by several later studies (e.g. Cruttenden 1970; Vihman

et al.

1985; Vihman 1996; Boysson-Bardies 1999). For example, French adults can pick out French baby babbles from non-French ones (Boysson-Bardies

et al.

1984). In this respect babbling is clearly distinct from crying, which has no discernible relationship with any one language. As one researcher commented:

The voices of children all over the world do, of course, have much in common; but listening to their babbling and first words, we see that the young language learners have already captured the characteristic colour and tone of their native languages.

(Boysson-Bardies 1999: 68)

A question which perhaps should be asked at this stage is the following: how much can children actually distinguish of their parents’ speech? It is sometimes assumed that babies hear merely a general mish-mash of sound, and only gradually notice details. However, infants may be capable of discriminating a lot more than we realize. They seem to be specially pre-set to notice the rhythms and sounds of speech, and probably begin to ‘tune in’ before birth. French infants as young as four days old can distinguish French from other languages, according to one group of researchers (Mehler

et al.

1988). They found this out by giving babies pacifiers (dummies) to suck. It is well known that infants suck more strongly when they are aroused and interested in what they hear. These French newborns sucked at significantly higher rates when exposed to French, than to English or Italian. So they had possibly become acclimatized to the rhythm and intonation of French while still in the womb.

Using the same sucking technique, other investigators (Eimas

et al.

1971; Eimas 1985) had already shown that babies between 1 and 4 months old can

distinguish between P and B. The investigators started by playing a repeated B sound, then they switched to P. The babies suddenly increased their sucking rate, showing that they had noticed the alteration. So even though infants may not listen carefully to everything their parents say, they may well be capable of hearing a considerable amount from a very young age. Somewhat surprisingly, these results have been replicated with rhesus monkeys and chinchillas (Kuhl and Miller 1974, 1975; Morse 1976), and so may be due to the hearing mechanisms in certain types of mammals, and not just humans alone. In brief, a child’s perception may be much sharper than had previously been supposed, even though it may not be equivalent to an adult’s for some time (Fourcin 1978).

Simultaneously with babbling, and from around 8 or 9 months, Barbara began to imitate

intonation patterns

. These made her output sound so like speech that her mother sometimes said ‘I’m sure she’s talking, I just can’t catch what she’s saying.’ An eighteenth-century German researcher observed of this stage: ‘He attempted to imitate conversations, to which end he produced a profusion of incomprehensible sounds’ (Tiedemann 1782, in Bar-Adon and Leopold 1971: 15). English mothers have noted that their children often use a ‘question’ intonation, with a rise in tone at the end of the sentence. This may be due to a normal parent’s tendency to bend over the child, asking, ‘What are you trying to say then?’ ‘Do you want some milk?’ ‘Do you know who this is?’ and so on.

Somewhere between 1 year and 18 months Barbara began to utter

single words

. She continued to babble as well, though her babbling gradually diminished as true language developed (Stoel-Gammon and Cooper 1984). The number of single words acquired at around this time varies from child to child. Some have only four or five, others have around fifty. As an average child Barbara acquired about fifteen. Many of them were names of people and things, such as UF (woof) ‘dog’, DABA ‘grandma’, DA ‘doll’.

Then as she neared her second birthday, she reached the more impressive

twoword stage

. From the time Barbara started to put words together she seemed to be in a state of ‘language readiness’, and mopped up language like a sponge. The most noticeable feature of this process was a dramatic increase in her vocabulary. By the time she was 2½ years old, she knew several hundred words. Meanwhile, there was a gradual but steady increase in her average or mean length of utterance – usually abbreviated to MLU. MLU is calculated in terms of grammatical items or ‘morphemes’: plural -S and past tense -D, for example, each count as one item and so do ordinary words such as MUMMY and BATH. Compound words such as BIRTHDAY and QUACK-QUACK also count as a single item (Brown 1973: 54). Many, but not all, researchers accept this as a useful gauge of progress – though the child with the longest utterances does not necessarily have the most grammatically advanced, or even the most grammatically correct utterances (Bates

et al.

1988; Bennett-Kastor 1988).

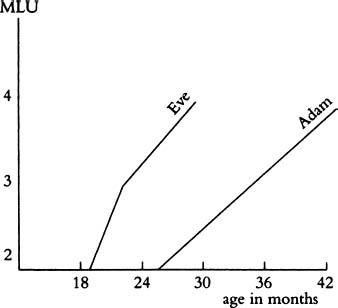

The fact that a steady increase in MLU occurs from the age of around 2 onwards has been shown by Roger Brown of Harvard University, who carried out a detailed study of the speech development of three unacquainted children, Adam, Eve and Sarah – though he found that the chronological age at which different children reached an MLU stage differed considerably (Brown

et al.

1968; Brown 1973). A comparison of Adam and Eve showed that Eve outstripped Adam by far. Eve’s MLU was two items at around 20 months, three at 22 months and four at 28 months. Adam was over 26 months old before he achieved an MLU of two items. He was nearly 3 years old before his MLU reached three items and 3½ before it reached four items – a whole year behind Eve.

If we assume that Barbara is not as advanced as Eve, but ahead of Adam, she possibly had an MLU of two items a little before her second birthday, an MLU of three items at 2½, and four items around her third birthday.

In the early part of the two-word stage, when she was around 2 years old, Barbara’s speech was ‘telegraphic’. She sounded as if she was sending urgent telegrams to her mother: WANT MILK, WHERE DUCK? As in a real telegram, she tended to preserve the nouns and verbs in the correct order, but omitted the ‘little’ words such as THE, A, HAS, HIS, AND. She also left out word endings, such as the plural -S or past tense -D, as in TWO SHOE and MILK SPILL.

How much do children understand at this time? Most parents confidently claim that children understand much more language than they can produce. But dog-owners sometimes make the same assumption about their pets, so how can anyone know for sure? Psychologists have discovered that children prefer pictures that match what they are hearing. This has inspired an ingenious experiment. A child is read out a sentence which corresponds to one of two pictures being shown on two television screens in front of him (Hirsh-Pasek and Golinkoff 1996).

For example, the youngster might be shown a popular TV character, such as Cookie Monster, one of a family of ‘Muppets’ who feature in the American children’s programme

Sesame Street

. Cookie Monster is a large fluffy creature who is covered in blue fur, has big bulging eyes and a voracious appetite for chocolate cookies. On one screen, Cookie Monster would be made to tickle Big Bird, another character from the same show. On the other screen, Big Bird would be tickling Cookie Monster. Then a sentence would be played, either ‘Look! Cookie Monster is tickling Big Bird!’ or ‘Look! Big Bird is tickling Cookie Monster!’ If the child understands the difference between the sentences, he or she tends to show a preference for the screen which matches the picture, and the time taken to focus on this can be measured. Such experiments have confirmed parental and researchers’ intuitions, that children’s comprehension is normally ahead of their production.

To return to Barbara, once the two-word stage is firmly in place, then, gradually, the ‘little’ words and

inflections

are added. ‘All these, like an intricate work of ivy, begin to grow up between and upon the major construction blocks, the nouns and verbs’ (Brown 1973: 249).

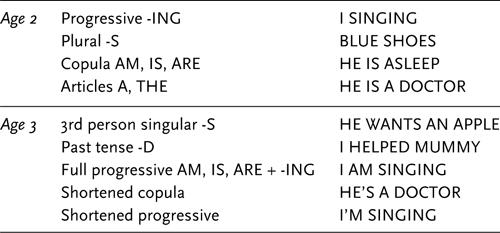

In this aspect of language, Barbara is following the same path of development as the Harvard child Adam, but at a slightly earlier age (Brown 1973: 271). Between the ages of 2 and 3½, Barbara acquired the following grammatical forms:

It is important to distinguish between the

emergence

, or first appearance of an ending, and its

acquisition

, its reliable use in the places where an adult would expect to find it. An ending can be considered acquired if it occurs in at least 90 per cent of the contexts where it is needed (Brown 1973: 258).

The actual age at which Barbara acquired each form is not significant because it varies widely from child to child. What is important and interesting is the

order

of acquisition. The sequence seems surprisingly similar among English-speaking children. Roger Brown noted that in the unacquainted Harvard children, the developmental order of these grammatical

forms was ‘amazingly consistent’. There were one or two minor variations: Sarah, for example, acquired the progressive -ING after the plural, whereas Adam and Eve acquired it before. But in all the children, both the progressive -ING and the plural -S occurred before the past tense, the third person singular -S, and the copula AM, IS, ARE.

Perhaps even more surprising, is the fact that in all the Harvard children the copula AM, IS, ARE as in I AM A DOCTOR developed before AM, IS, ARE when it was part of the progressive construction, for example, I AM SINGING. And the shortened copula as in HE’S A BEAR came before the shortened progressive, for example HE’S WALKING. This is quite an astonishing discovery. Although we might expect children to go through similar general lines of development, there seems to be no obvious reason why a variety of English children should correspond so closely in their acquisition of specific items. Possible reasons for this phenomenon will be discussed in

Chapter 7

.