The Articulate Mammal (36 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

JOHN PHONES UP THE GIRL.

and

JOHN PHONES THE GIRL UP.

If the correspondence hypothesis or DTC was correct, the second should be more difficult, according to the ‘classic’ version of transformational grammar, because a ‘particle separation’ transformation had been applied, separating PHONES and UP. Worse still for the theory were sentences such as:

BILL RUNS FASTER THAN JOHN RUNS.

BILL RUNS FASTER THAN JOHN.

The second sentence had one more transformation than the first, because the word RUNS had been deleted. In theory it should be more difficult to comprehend, but in practice it was easier.

Fodor and Garrett followed their 1966 conference paper with another article in 1967 where they pointed out more problem constructions (Fodor and Garrett 1967). For example, DTC counter-intuitively treated ‘truncated’ passives such as:

THE BOY WAS HIT.

as more complex than full passives such as:

THE BOY WAS HIT BY SOMEONE.

After this, researcher after researcher came up with similar difficulties. According to DTC:

THERE’S A DRAGON IN THE STREET.

should have been more difficult to process than:

A DRAGON IS IN THE STREET.

Yet the opposite is true (Watt 1970). And so on.

Both the correspondence hypothesis and DTC had to be abandoned. Transformational grammar in its ‘classic’ form was not a model of the production and comprehension of speech, and derivational complexity as measured in terms of transformations did not correlate with processing complexity. Clearly, Chomsky was right when he denied that there was a direct relationship between language knowledge, as encapsulated in a 1965 version of transformational grammar, and language usage.

THE DEEP STRUCTURE HYPOTHESIS

By the mid-1960s, the majority of psycholinguists had realized quite clearly that transformations as then formulated had no direct relevance to the way a person produces and understands a sentence. However, the irrelevance of transformations did not mean that other aspects of transformational grammar were also irrelevant. So in the late 1960s another hypothesis was put forward – the suggestion that when people process sentences, they mentally set up a Chomsky-like deep structure. In other words, when someone produces, comprehends or recalls a sentence, ‘the speaker-hearer’s internal representation of grammatical relations is mediated by structures that are isomorphic to those that the grammatical formalism employs’ (Fodor

et al.

1974: 262). Some ‘click’ experiments were superficially encouraging (Bever,

et al.

1969).

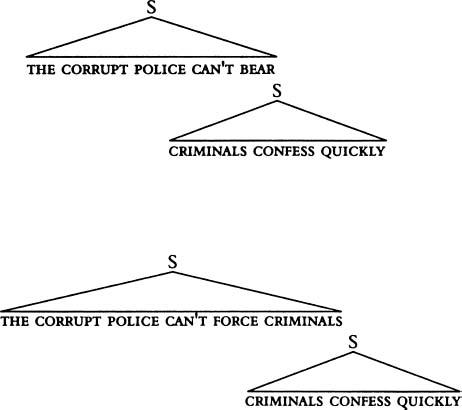

The aim of the ‘click’ experiments was to test whether a person recovers a Chomsky-like deep structure (1965 version) when she decodes. The experimenters took pairs of sentences which had similar surface structures, but different deep structures. For example:

THE CORRUPT POLICE CAN’T BEAR CRIMINALS TO CONFESS QUICKLY.

THE CORRUPT POLICE CAN’T FORCE CRIMINALS TO CONFESS QUICKLY.

In the first sentence, the word

criminals

occurred once only in the deep structure, but in the second sentence it occurred twice according to a ‘classic’ transformational model. If anyone doubts that these sentences have a different deep structure, try turning them round into the passive, and the difference becomes clear: the first sentence immediately becomes quite ungrammatical, though there is nothing wrong with the second:

*CRIMINALS CANNOT BE BORNE BY THE POLICE TO CONFESS QUICKLY.

CRIMINALS CANNOT BE FORCED BY THE POLICE TO CONFESS QUICKLY.

In the experiment, the subjects were asked to wear headphones. Then the sentences were played into one ear, and a ‘click’ which occurred during the word CRIMINALS was played into the other. Subjects were asked to report whereabouts in the sentence they heard the click. In the first sentence, subjects tended to hear the click

before

the word CRIMINALS, where a Chomskyan deep structure suggests a structural break:

But in the second sentence, the click stayed still, as if the hearers could not decide where the structural break occurred. They behaved as if CRIMINALS

straddled the gap between the two sections of the sentence. Since CRIMINALS occurred twice in the deep structure, with the structural break between the two occurrences, this was an encouraging result:

THE CORRUPT POLICE CAN’T FORCE CRIMINALS/CRIMINALS TO CONFESS QUICKLY.

This suggested that people might recover a ‘classic’ deep structure when they decoded a sentence.

But one swallow does not make a summer, and one experiment could not maintain the validity of deep structure. Both the design and interpretation of this particular experiment have been challenged. The results might have been due to the unusual experimental situation, or they could have been connected with meaning rather than with an underlying deep structure syntax (Fillenbaum 1971; Johnson-Laird 1974). The use of clicks and the ‘muddled history of clickology’ (Johnson-Laird 1974: 138) was, and still is a source of considerable controversy.

To summarize, a few early experiments were

consistent

with the suggestion that people recover a Chomsky-like deep structure when they recalled or understood sentences. But they were consistent with other hypotheses also. All that we could be sure about was that underlying every sentence was a set of internal relations which may well not be obvious on the surface. As Bever noted (1970: 286):

The fact that every sentence has an internal and external structure is maintained by all linguistic theories – although the theories may differ as to the role the internal structure plays within the linguistic description. Thus talking involves actively mapping internal structures on to external sequences, and understanding others involves mapping external sequences on to internal structures.

In other words, it is very

unlikely

that we recover a Chomskyan (1965) deep structure when we understand sentences, though no one ever totally disproved this possibility.

The key point is, science proceeds by

disproving

hypotheses, not by proving them. Suppose you were interested in flowers. You might formulate a hypothesis, ‘All roses are white, red, pink, orange or yellow.’ There would be absolutely no point at all in collecting hundreds, thousands or even millions of white, red, pink, orange and yellow roses. You would merely be collecting additional evidence consistent with your hypothesis. If you were genuinely interested in making a botanical advance, you would send people in all directions hunting for black, blue, mauve or green roses. Your hypothesis would stand until somebody found a blue rose. Then, in theory, you should be delighted that botany

had made progress, and found out about blue roses. Naturally, when you formulate a hypothesis it has to be one which is capable of disproof. A hypothesis such as ‘Henry VIII would have disliked spaceships’ cannot be disproved, and consequently is useless. A hypothesis such as ‘The planet Neptune is made of chalk’ would have been useless in the year AD 100, when there was no hope of getting to Neptune – but it is a perfectly legitimate, if implausible, one in the twenty-first century when planet probes and space travel are becoming routine.

This leads us back to Chomsky. Some people have claimed that because deep structures could not be disproved, they were useless as a scientific hypothesis. It is true that, at the moment, it is difficult to see how they might have been tested. But psycholinguistic experimentation takes steps forward all the time. Perhaps with the development of further new techniques, ways will be found of definitively disproving theories about the ‘inner structure’ of a language. At the moment, as one psycholinguist noted ‘Presently available evidence on almost any psycholinguistic point is so scanty as to blunt any claim that this or that hypothesis has truly been disconfirmed’ (Watt 1970: 138). The same is true today.

To sum up, the suggestion that people utilize a Chomskyan deep structure (1965 version) when they comprehend or produce sentences seems increasingly unlikely, but the hypothesis has not been truly disconfirmed. So was this work all wasted? Probably not. At the very least, it has enabled us to think more clearly about language and what it involves.

THE LINGUISTIC ARCHIVE

We have now come to the conclusion that 1965-style transformations are irrelevant to sentence processing, and that deep structure is quite unlikely to be relevant. But some steps forward have been made.

We are coming round to the view that a classic (1965) transformational grammar represents metaphorically a kind of archive which sits in the brain ready for consultation, but is possibly only partially consulted in the course of a conversation. Perhaps it could be likened to other types of knowledge, such as the knowledge that four times three is the same as six times two. This information is mentally stored, but is not necessarily directly used when checking to see if the milk bill is correct.

The information is probably represented in the brain in a rather different way from that suggested in a 1965-style transformational grammar. But such a grammar might provide a useful way of encapsulating speakers’ latent knowledge of their language.

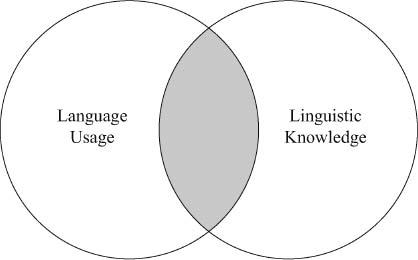

We are

not

assuming a clean break between language knowledge and language usage. In practice the two overlap to a quite considerable extent, and the extent of the overlap varies from sentence to sentence.

Let us take a simple example:

AUNT AGATHA WAS RUN OVER LAST THURSDAY.

A short passive of this type is generally simpler and quicker to comprehend than a full passive such as:

AUNT AGATHA WAS RUN DOWN BY SOMEONE (OR SOMETHING) LAST THURSDAY.

It therefore seems quite unnecessary to suppose that, in order to understand the sentence, hearers have to recover a Chomsky-like deep structure which includes the agent SOMEONE (or SOMETHING):

SOMEONE (OR SOMETHING) RAN OVER AUNT AGATHA LAST THURSDAY.

Instead, they may not pay attention to the agent, they may be too busy thinking about Aunt Agatha. However, if they

did

spend rather longer pondering about the sentence, they could recover not only the agent SOMEONE (or SOMETHING) which the ‘classic’ deep structure suggests, but much more information in addition (Watt 1970). They could suggest that Aunt Agatha was run over by SOMETHING, rather than SOMEONE, and that this something was probably a MOVING VEHICLE. They obtained all this information from their knowledge of the lexical item RUN OVER – but it is optional whether they use it or not when they comprehend the sentence.